It’s apparent Paul Thomas Anderson lovingly pinches his opening shot from American Graffiti as his boyish hero Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman in his debut) primps in front of a bathroom mirror, a toilet all but exploding behind him. The whole movie is born out of a chance meeting at a school picture day, but it would come to nothing if Alana Kane (Alana Haim also in her debut) does not take him up on the proposition to meet at a local watering hole. Why does she do it? She’s 25, at least. He’s 15.

It’s apparent Paul Thomas Anderson lovingly pinches his opening shot from American Graffiti as his boyish hero Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman in his debut) primps in front of a bathroom mirror, a toilet all but exploding behind him. The whole movie is born out of a chance meeting at a school picture day, but it would come to nothing if Alana Kane (Alana Haim also in her debut) does not take him up on the proposition to meet at a local watering hole. Why does she do it? She’s 25, at least. He’s 15.

It seems suspect, and the film never tries to explain. It feels like a bit of nostalgic, rose-colored wish fulfillment, and yet we come to understand Alana doesn’t know what she’s doing with her life. Perhaps it’s Gary’s charisma that draws her in. He’s got a lot of nerve, but he also knows how to hustle and people gravitate toward him. She acts as his chaperone on a press junket back east for one of his adolescent TV credits.

They get into the water bed business, and there are the expected hijinks involving deliveries; Gary even gets arrested momentarily. It’s the 1970s. Gasoline shortages have been hitting everyone hard. Although Anderson draws early comparisons to Graffiti, his film lacks the same fated structure. Graffiti is roving and far-ranging, yes, and yet it’s focused on one night in one town. Once it’s over, we know each of our characters will have changed in very specific ways. The moment is gone forever.

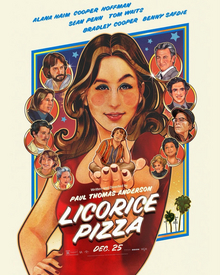

Licorice Pizza looks deceptively disorganized and free-flowing. It continually combs in these vignettes bringing in other personalities like Sean Penn, Tom Waits, Bradley Cooper, and Benny Safdie. Here it’s no longer solely about our leading “couple” and comfortably pushes their relationship to the periphery to play out against this wacky, narcissistic, and sometimes tragic world around them. It’s a world that Anderson waxes nostalgic about because it effectively resurrects the periphery of his childhood and old Hollywood haunts.

As time passes, it feels more and more like a Hal Ashby flick – a filmmaker who remains emblematic of the seventies – whether the politics, the music, or even for providing a precursor to our somewhat cringe-worthy leading couple. There’s also the hint of political intrigue along with the menace of Taxi Driver that suggests the paranoia of the contemporary moment.

Still, what prevails is the mimetic tableau and the warmer tones. Anderson’s film is also bathed in the glorious golden hues of the bygone decade. As Licorice Pizza progresses (or digresses), at times I felt like it had lost me. Where was our denouement and where was this serpentine trail leading us beyond its impressive display of period dressings?

Even Quentin Tarrantino’s somewhat analogous Once Upon a Time in Hollywood… has an inevitable ending that we know is coming like Graffiti before it. In Anderson’s film we do get something…eventually. It involves a lot of running, pinball machines, and our two leads reunited again.

Given the turns by Haim and Hoffman, it’s a testament to what they’re able to accomplish together that we do feel like we have some form of resolution. Boy oh boy, is this a casual movie and that’s generally a compliment. Thankfully our two leads are full of so much winsome charm and good-natured antagonism to make it mostly enjoyable.

The movie relies heavily on a killer soundtrack, and the era-appropriate humor feels uncomfortable at best. I like John Michael Higgins as much as the next guy. However, even if his oafish Japanese restaurateur with his revolving door of Japanese wives is based on a real entrepreneur in the valley, it doesn’t mean the casual racism doesn’t still feel queasy.

Especially when you can’t discern if the audience is laughing at him or with him. Because the implicit punchline could easily be misconstrued to be that Japanese culture feels foreign and weird without appreciating the cultural subtext of these scenes.

Still, there are ample moments to appreciate the film and cheer for Gary and Alana. We need their charisma and they more than come through. I will say that Blood, Sweat, and Tears’ “Lisa, Listen To Me” might be my favorite deep cut of the year. It’s so good, in fact, that Anderson uses it twice.

4/5 Stars

Note: This review was originally from 2022