“The Cast and Crew of Star Trek wish to dedicate this film to the men and women of the spaceship Challenger whose courageous spirit shall live to the 23rd century and beyond…”

“The Cast and Crew of Star Trek wish to dedicate this film to the men and women of the spaceship Challenger whose courageous spirit shall live to the 23rd century and beyond…”

The opening remarks of The Voyage Home honoring the “courageous spirit” of those lost on The Challenger is a perfect encapsulation of the ethos of Star Trek.

Because it was always very much a franchise that was a social allegory for our world and by taking place in a sci-fi future, it was able to champion all that was good and valorous of people living through a space age even as they tried to reconcile with living with one another on earth with fraternity.

As a kid, Voyage Home was always my favorite Star Trek movie, and probably still remains so now. I’m not quite sure what it was exactly, though I do have some ideas. It’s important to acknowledge it right out front. Voyage Home has a wild and wonky premise full of a certain incredulity, but it’s also a good deal of fun.

Spock is back after Star Trek III, but now there is a new problem: Not only is Kirk a wanted man, but a frequency of humpback whale calls is causing chaos to reverberate all throughout the galaxy. Yes, you heard that right.

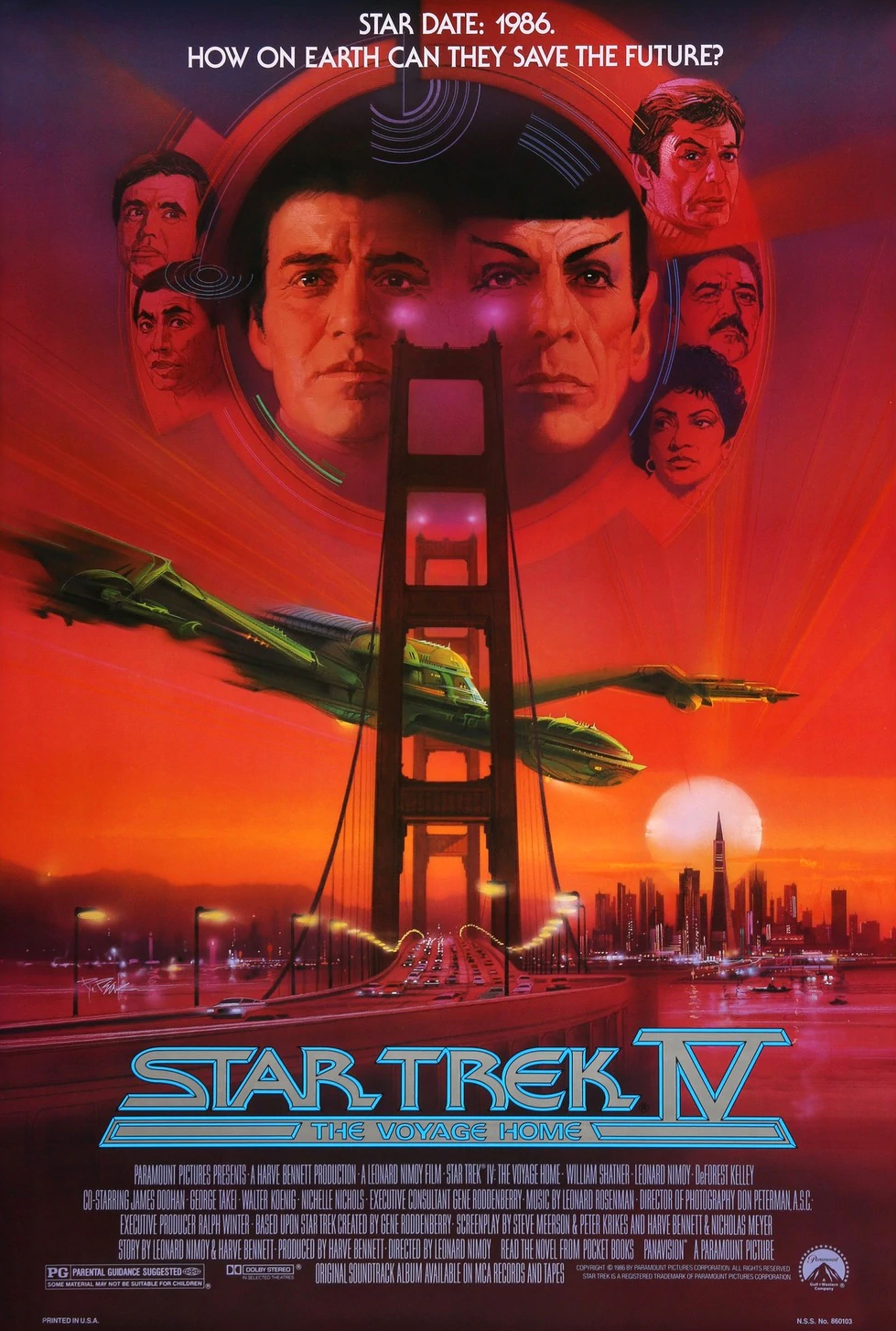

Kirk leads his fugitive compatriots on a Klingon ship with cloaking capabilities to time travel to the past — that is, the contemporary moment the film came out — 1986. The wheels start turning.

I’m no Star Trek savant, but it didn’t evade me that this is a subtle twist on the notable “City On The Edge of Forever” episode that sent Kirk and Spock (with his ear-concealing bandana) back in time to the soup lines of the Great Depression.

Voyage Home mines most of its comedy from your typical fish out of water premise, in this case pitting the Enterprise Crew of highly intelligent and advanced space cadets against a world that feels so analog and decidedly archaic to their sensibilities. Meanwhile, to the average guy on the street they look like helpless weirdoes.

A particularly memorable vignette involves a spiky-haired punk rocker on the bus with his blaring boombox. He does look rather like an alien to anyone left unawares from a different century. A little Vulcan nerve pinch gets the whole bus clapping with appreciation for curbing the noise.

Pairing Bones and McCoy off together is a pleasure in its own right, though it need not be expounded upon in depth here. The rest of the crew is entrusted to build a tank to carry the whales across the galaxy and also locate a nuclear reactor to help power their ship home.

Spock’s coming up to speed with the modern vernacular offers its own hilarity as does his commune with the whales in their enclosure at a Sausalito aquarium. It’s in plain view of everyone and another breach of societal norms. This just isn’t done in the 20th century. Spock has greater concerns as Kirk tries to guide him through this strange world like a blind man leading a blind Vulcan.

The resident biologist Dr. Gillian Taylor (Catherine Hicks) is incensed. She cares about these animals’ well-being deeply. Later, she offers a ride our two lovable nut jobs up in her pickup because she has a penchant for hard-luck cases.

The addition of Hicks in a fairly substantial role begins as a screwball comedy with her skeptical incredulousness around Kirk and Spock. It then builds into a kind of swelling romantic comedy served with a side of pizza pie. Somehow it plays as the less tragic inverse to Joan Collins turn in “City on The Edge of Forever.”

Because they push the boundaries of her belief and still, if she doesn’t quite have faith in their clear-eyed tall tales, she recognizes their shared mission to protect the whales. If it’s not quite faith, then her trust in them is rewarded in an extraordinary way as an unimaginable world of the 23rd century opens up before her eyes.

She always feels a bit out of step with the world around her, and then she finds these like-minded people, a little eccentric, and yet they suggest to her that she was made for so much more. It’s an extraordinary development.

Chekhov gets captured in a restricted area and is shipped off to a hospital in the city after he suffers an injury. Kirk and Bones lead a search and rescue mission masquerading in scrubs, then Gillian finds out the whales were shipped off early. They have to intercept them en route if they ever hope to save the whales and thereby the galaxy. No big deal.

Hanging out with the crew of the Enterprise in San Francisco sounds like a good time, and it’s a pleasure to assure everyone that it is. For such gargantuan stakes, Voyage Home feels surprisingly lightweight, lithe, and generally fun because we rarely feel burdened by them. It’s not bogged down by a lot of self-importance and this is to its credit. So it worked then, in my childhood, and it still holds up now eliciting the same kind of stirring reactions.

3.5/5 Stars