“When you came here that first day, I fell flat on my face over your suitcase. I never really got up.” – Joan Leslie as Donna

Born to Be Bad is not high-grade stuff. Its trashy exploitive title says as much, but it’s also worthwhile for exactly these reasons. Nicholas Ray would make a name for himself in Technicolor — not black and white — capturing a bevy of emotive performances from the likes of James Mason and James Dean. But it’s easy to forget some of his earlier films are equally stirring. Bogart in In a Lonely Place or Robert Ryan in On Dangerous Ground.

There’s something lighter, more convivial about the performances in Born to Be Bad, but straight down the line, it offers up a thoroughly intriguing cast. It has to do with how they can play off one another and couple up with various character dynamics forming between them.

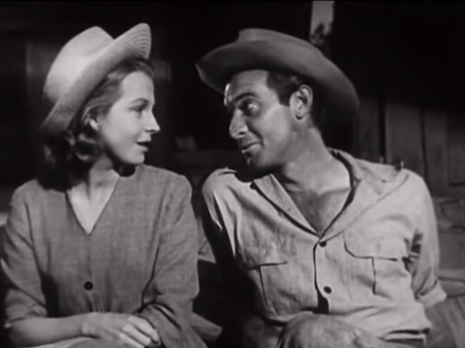

We have a disorientating beginning because we don’t see Joan Fontaine, but someone who turns out to be Joan Leslie. She’s older now, mature, assured, and still more ebullient than I ever remembered her before in the early Warner Bros. days.

Within the context of the picture, she has reason to be. She’s deliriously happy, about to marry the love of her life, a rich moneybags (Zachary Scott), and yet she still finds time for a job and other wisecracking male companions. One’s a painter (Mel Ferrer), the other a purported novelist (Robert Ryan). There’s a happy-go-lucky familiarity to it all. We almost forget what the movie is meant to be about.

Then, Joan Leslie trips over a suitcase, her hair tossed violently askew, and she looks up to see the soft features of none other than Joan Fontaine perched on a couch. The unassuming beauty is her usual diffident self. However, this iteration of her screen image holds a manipulative underbelly.

As Cristabel ingratiates herself into Donna’s good graces and initiates designs on her man, it’s almost easy enough to dismiss her actions as first. She wheedles her way bit by bit until it’s more and more evident her ingenue from Rebecca or Suspicion has gone sour and self-serving.

Even when he’s partially a victim, Zachary Scott manages to give off a smarmy veneer. Robert Ryan has his own curious introduction, berating Cristabel when she’s on the phone, but it’s not a party line. He’s in the house and she wanders into the kitchen to see the stranger raiding the icebox. At first, she’s indignant. Then she starts to fall for his blunt charms.

Ryan would join forces again with Ray in On Dangerous Ground, and he seems like the kind of actor the director can use well. There’s a raw incisiveness to him that can function durably without sacrificing certain levels of emotional honesty. Because he has an unsparing frankness about him that one can either appreciate or become royally turned off by. Very rarely does Ryan elicit an apathetic response.

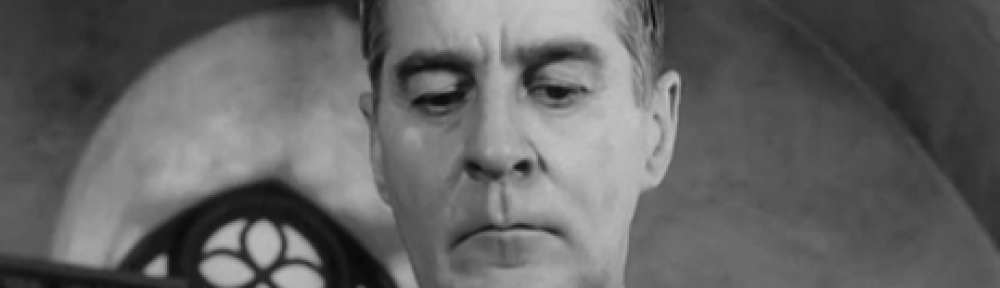

Fontaine does her part beautifully — her eyes constantly flittering around. In one particular conversation between Scott and Ferrer, she casually listens as she takes in the scene around her, just happy to be in such a place. She manages to be so helpful and so helpless getting everything she wants as a result.

Donna’s preparing to storm off to London, her relationship with Curtis torn asunder. Her pointed remarks to her rival have a delightful sting: “Somebody should have told the birds and the bees about you.” I don’t know what to make of it, but there’s something in Joan Leslie’s eyes when she’s been slighted that’s reminiscent of Marsha Hunt — a glint that Fontaine never owned. Leslie provides her a fine foil as we continue to explore a variation on the All About Eve dynamic.

Two exemplary shots of juxtaposition happen in adjacent scenes with Fontaine’s sparkling features framed on the chest of her man as she reposes there and, of course, there are two of them. She’s so good at flitting back and forth between two men. They both speak to her in different ways or rather, they both offer something unique that she can benefit from.

The jilted lovers, Leslie and Ryan, fall in together as friends and business associates if not romantic partners because there is something more in the works. Cristabel finally gets caught in her lies, though Born To Be Bad has a fairly lightweight ending. No one gets tragically wounded and everyone seems to laugh it off or get their wrist slapped. It’s not noir, nor is it effectively weighty, but it’s an intermittent pleasure to watch if you’re fond of the players. It more than lives up to its title.

3.5/5 Stars