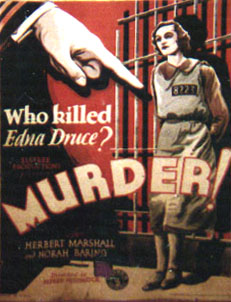

It’s so easy to quickly brush off early works of Hitchcock with admittedly bland titles like Blackmail (1929), Murder (1930), Secret Agent (1936), Sabotage (1936), etc. But if you actually dare to dust one of these films off for a viewing, you do see Hitchcock spinning his wizardry even if the edges are a bit worn, the stories barely developed, and the production values humble.

Among the ranks of Hitch’s thriller sextet, Secret Agent written by frequent collaborator Charles Bennett is a surprisingly lucid effort with a cast that is stacked quite nicely. John Gielgud is a bit bristly as our leading man and the chief secret agent in our loosely set WWI storyline while Madeleine Carroll (featured earlier in The 39 Steps) is decidedly more fun as the adventure-seeking gal by his side, augmented by a certain amount of ravishing vitality. They have quite the connubial relationship posing as a married couple. Still, there’s enough chemistry within the film’s running time for some breezy comedic moments that predate later romantic thrillers like To Catch a Thief (1955) and North by Northwest (1959).

In fact, part of the reason Gielgud’s Shakespearian sensibilities come off rather stuffy at times is not so much his fault but a testament to Carroll and Gielgud’s other male counterparts. The future all-knowing television father Robert Young makes his mark as a quipping American wiseguy constantly making passes at his latest acquaintance Mrs. Ashenden.

We meet him for the first time lounging in the lady’s hotel room in an amorous mood and he never ceases flirting, for the majority of the film anyway. Equally memorable is the spastic performance of Peter Lorre though he can’t quite pull off the stereotypical portrayal of General, the Hispanic sidekick supposedly spouting off Spanish in rapid fire and still speaking in a cannibalized English dialect with a German influence. There’s no denying he is colorful given Lorre’s usual aptitude for playing wonderful supporting spots.

Like many of Hitchcock’s films sandwiched together during the 1930s, this one exhibits the same precision plotting that sets out the parameters of the narrative early on including our hero, his background, and his goals, in this case to rendezvous with a double agent so they might weed out an enemy counterspy.

The objectives seem simple enough as our man Broden alias Ashenden must masquerade with his “Wife” and the eccentric “General” in the deceptively glamorous world of spies, secrets, and international intrigue. Hitchcock does make it a riveting world at that. A foreboding church with pounding organs and clanging bells is the scene of a murder. There’s a lively setup at a casino beckoning the future delights of films like Casablanca (1942) and Gilda (1946).

But there’s always bedlam waiting somewhere and in this case, it’s staged in a German chocolate factory as our English spies try to evade capture ratted out by a faceless snitch. The final act rumbles along on a hurtling train still behind enemy lines with the British air force raining down a hail of bullets. It’s the prototypical spectacle for a Hitchcockian showdown with unconventional results.

One of the most impressive aspects of Secret Agent is how many people Hitchcock is able to crowd in the frame balancing medium shots with close-ups and maneuvering his camera this way and that around his character’s many interactions. It evokes that not so famous adage that film is both what is in the frame and what is left out. Here we have a film that makes us very aware of what we are looking at and that is a hallmark of this man. He very rarely allows his camera to be a passive observer unless he chooses for it to be.

4/5 Stars

Note: It’s only a small aside but I only realized moments after the movie ended that even a young Lilli Palmer made an appearance as General’s beau.

Although Hitchcock did many riffs off the same themes, he very rarely tried to do the same film twice over. The Man Who Knew Too Much might be the one exception and even then if you place these two thrillers from 1934 and 1956 up next to each other, they’re similarities are fairly nominal.

Although Hitchcock did many riffs off the same themes, he very rarely tried to do the same film twice over. The Man Who Knew Too Much might be the one exception and even then if you place these two thrillers from 1934 and 1956 up next to each other, they’re similarities are fairly nominal. Alfred Hitchcock captures the pure bedlam that overtakes a neighborhood when their peaceful dreams are rudely disrupted by an awful din. As is customary everyone is in a foul mood, peers out their windows, bickers with everyone else, and moves into action.

Alfred Hitchcock captures the pure bedlam that overtakes a neighborhood when their peaceful dreams are rudely disrupted by an awful din. As is customary everyone is in a foul mood, peers out their windows, bickers with everyone else, and moves into action. “Blessed are the poor in spirit for their’s is the kingdom of heaven”

“Blessed are the poor in spirit for their’s is the kingdom of heaven” Again, I must confess that I have not read yet another revered American Classic. I have not read A Farewell to Arms…But from the admittedly minor things I know about Hemingway’s prose and general tone, this film adaptation is certainly not a perfectly faithful translation of its source material. Not by any stretch of the imagination.

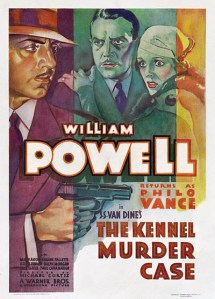

Again, I must confess that I have not read yet another revered American Classic. I have not read A Farewell to Arms…But from the admittedly minor things I know about Hemingway’s prose and general tone, this film adaptation is certainly not a perfectly faithful translation of its source material. Not by any stretch of the imagination. It’s happened in some well-documented cases that the same actor has played two characters that feel nominally similar and based on this cursory level of comparison the general public has been forever befuddled. You could cite some notable examples being Bogart playing Sam Spade and Phillip Marlowe the archetypal pulp private eye heroes of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.

It’s happened in some well-documented cases that the same actor has played two characters that feel nominally similar and based on this cursory level of comparison the general public has been forever befuddled. You could cite some notable examples being Bogart playing Sam Spade and Phillip Marlowe the archetypal pulp private eye heroes of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.

Destry Rides Again is integral to the tradition of comedy westerns–a storied lineage that includes the likes of Way Out West, Blazing Saddles, and Support Your Local Sheriff. It takes a bit of the long maintained western lore and gives it a screwy comic twist courtesy of classic Hollywood.

Destry Rides Again is integral to the tradition of comedy westerns–a storied lineage that includes the likes of Way Out West, Blazing Saddles, and Support Your Local Sheriff. It takes a bit of the long maintained western lore and gives it a screwy comic twist courtesy of classic Hollywood.