The opening credits roll and recognition comes with each name that pops on the screen. Jean Arthur, James Stewart, Claude Rains, Edward Arnold, Guy Kibbee, Thomas Mitchell, Eugene Palette, Beulah Bondi, H.B. Warner, Harry Carey, Porter Hall, Charles Lane, William Demarest, Jack Carson, and of course, Frank Capra himself.

The opening credits roll and recognition comes with each name that pops on the screen. Jean Arthur, James Stewart, Claude Rains, Edward Arnold, Guy Kibbee, Thomas Mitchell, Eugene Palette, Beulah Bondi, H.B. Warner, Harry Carey, Porter Hall, Charles Lane, William Demarest, Jack Carson, and of course, Frank Capra himself.

We are met with the ubiquitous visage of Charles Lane calling in a big scoop on the telephone. A senator has died suddenly. The likes of Porter Hall and H.B. Warner fill the Senate Chamber presided over by a wryly comic VP, Harry Carey. Corruption is personified by the flabby pair of Edward Arnold and Eugene Palette while Claude Rains embodies the tortured political journeyman. The eminent members of the press include not only Lane but the often swacked Thomas Mitchell and a particularly cheeky Jack Carson.

To some people, these are just names much like any other but to others of us, linked together and placed in one film, these figures elicit immense significance and simultaneously help to make Mr. Smith Goes to Washington one of the most satisfying creations of Hollywood’s Golden Age from arguably “The Greatest Year in Cinematic History.” The acting from the biggest to the smallest role is a sheer joy to observe as is Capra’s candid approach to the material.

As someone with a deep affection for film’s continued impact, it gives me great pleasure that stories such as Mr. Smith exist on the silver screen if only for the simple fact that they continually renew my belief in humanity, whatever that means. Because it’s an admittedly broad, sweeping statement to make but then again that’s what Frank Capra was always phenomenally skilled at doing. He could take feelings, emotions, beliefs, and ideals synthesizing them into the perfect cultural concoctions commonly known as moving pictures.

But his pictures always maintained an unfaltering optimism notably in the face of all sorts of trials and tribulations. He never disregarded the corruption dwelling in his stories–it was always there–in this case personified by the stifling political machine of Jim Taylor gorging itself off the lives of the weak and stupid.

The key is that his narratives always rise above the graft and corruption. They latch onto the common everyday decency, looking out for the other guy, and in some small way uphold the great commandment to love thy neighbor.

Politics have never been my forte. Like many others, I’m easily disillusioned by “politics” as this becomes a dirty word full of arrogance, partisanship, and scandal among other issues. It seems like the founding principles that laid the groundwork for this entire democracy often get buried under pomp & circumstance or even worse personal ambitions.

Although this film was shot over 75 years ago everyone who’s been around the block lives as if that’s the case then too and so they’re not all that different from today at least where it matters. Cynicism is a hard thing to crack when it runs through the fabric of society from the politicians, to the newspapers, all the way down to the general public. It’s not hard to understand why. Still, the genuine qualities of a man like Jefferson Smith can act as a bit of an antidote. He as a character himself might be a bit of an ideal, yes, but I’d like to have enough faith to believe that people with a little bit of Jefferson Smith might still live today.

Common, everyday people who nevertheless are capable of extraordinary things like standing up for what’s right when they know that no one else will or when they know all that waits for them at the end of the tunnel is disgrace. But the promise of what is beyond the tunnel is enough. That is true integrity to be able to do that and those are the causes worth cheering for when David must fight Goliath and still he somehow manages to overcome. That’s the chord Mr. Smith strikes with me. thanks in part to Capra’s vision but also Stewart’s impassioned embodiment of those same ideals. He has a knack for compelling performances to be sure.

Time and time again James Stewart pulls me in. His career is one of the most iconic in any decade, any era no questions asked. There are so many extraordinary films within that context perhaps many that are technically or artistically superior to Mr. Smith by some estimations, but he was never more candid or disarming than those final moments in the senate chambers as he fights for his life — clinging to the ideals that he’s been such a stalwart proponent for even as his naivete has been mercilessly stripped away from him.

In the opening moments, his eyes carried that glow of honest to goodness optimism, his posture gangly and unsure represented all that is genuine in man. Now watching those same ideals and heroes come back to perniciously attack him, he presides with almost reckless abandon. Is he out of his mind? At times, it seems so, but as he wearies, his hair becomes more disheveled, and his vocal chords have only a few rasps left he still fights the good fight. There’s an earnest zeal to him that’s positively palpable.

As our stand-in, Saunders (Jean Arthur) first writes him off as a first class phony or at the very least a political stooge ready to do another man’s bidding but she does not know Jefferson Smith though she does grow to love him. And Arthur’s performance truly is a masterful one because without her Smith would hardly be the same figure. She brings out his naivete by sheer juxtaposition but she also puts the fight back into him because he brought a change over her that in turn rallies him to keep on pushing. They’ve got a bit of a mutually symbiotic relationship going on in the best way possible. You might call it love.

Capra repeatedly underlines Smith’s honesty and genuine nature not only through numerous rather simplistic montages of Capitol Hill and the surrounding national monuments but in the very way his character carries himself around others. He never assumes a position of superiority. He’s always humble. He sees the inherent need to raise up young people well so that they might progress to become the leaders of tomorrow with a great deal to offer our world. He fumbles with his hat in the presence of pretty girls and holds his idols in the highest esteem. It’s all there on Stewart’s face and in his actions. We too comprehend the solemnity and the gravity that he senses in the office of the Senate.

While this was not Jimmy Stewart’s debut and it was only at the beginning of a shining career as has already been noted, it was in these moments that the cinematic world fell in love with him. He can’t be licked and for good reason. He was never one to give up on lost causes just like his father before him.

I guess this is just another lost cause, Mr. Paine. All you people don’t know about lost causes. Mr. Paine does. He said once they were the only causes worth fighting for, and he fought for them once, for the only reason any man ever fights for them: Because of one plain simple rule: Love thy neighbor. ~ James Stewart as Jefferson Smith

5/5 Stars

“He could never fit in with our distorted viewpoint, because he’s honest, and sincere, and good. If that man’s crazy, Your Honor, the rest of us belong in straitjackets!” ~ Jean Arthur as Babe Bennett

“He could never fit in with our distorted viewpoint, because he’s honest, and sincere, and good. If that man’s crazy, Your Honor, the rest of us belong in straitjackets!” ~ Jean Arthur as Babe Bennett

When put up against more sophisticated brands of humor and satirical wit, it would be easy to call the likes of Laurel & Hardy the lowest form of comedy. It sounds degrading but it’s also quite true. Their pictures are short. They’re for all intent and purposes plotless aside from one broad overarching objective. Their gags are simple. Pratfalls. Mannerism. Foibles. Visual gimmicks. More pratfalls and mayhem. It’s not brain science. It’s not reinventing the wheel. So, yes, it might be the simplest brand of comedy but it also might just be the funniest and most universal comedy out there.

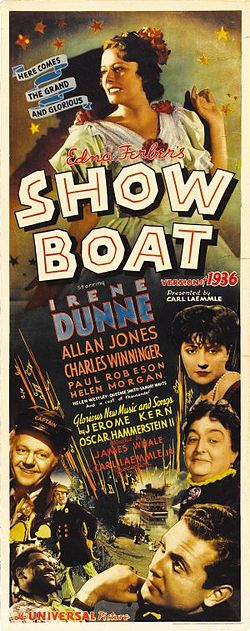

When put up against more sophisticated brands of humor and satirical wit, it would be easy to call the likes of Laurel & Hardy the lowest form of comedy. It sounds degrading but it’s also quite true. Their pictures are short. They’re for all intent and purposes plotless aside from one broad overarching objective. Their gags are simple. Pratfalls. Mannerism. Foibles. Visual gimmicks. More pratfalls and mayhem. It’s not brain science. It’s not reinventing the wheel. So, yes, it might be the simplest brand of comedy but it also might just be the funniest and most universal comedy out there. Most of what I know about riverboats can be gleaned from Mark Twain, Davy Crockett and the River Pirates, and that ever beloved Snoopy incarnation The World Famous River Boat Gambler. The 1936 musical Show Boat falls into that very same rich tradition but some clarification is in order.

Most of what I know about riverboats can be gleaned from Mark Twain, Davy Crockett and the River Pirates, and that ever beloved Snoopy incarnation The World Famous River Boat Gambler. The 1936 musical Show Boat falls into that very same rich tradition but some clarification is in order. Before the exoticism of Casablanca, Algiers, or even Road to Morroco, there was Josef Von Sternberg’s just plain Morocco but it’s hardly a run-of-the-mill romance. Far from it.

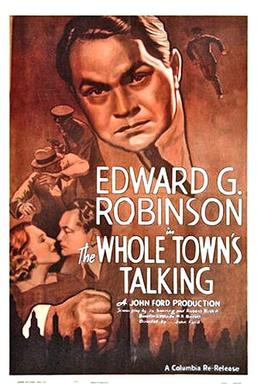

Before the exoticism of Casablanca, Algiers, or even Road to Morroco, there was Josef Von Sternberg’s just plain Morocco but it’s hardly a run-of-the-mill romance. Far from it. Comic mayhem was always supercharged in the films of the 1930s because the buzz is palpable, the actors are always endowed with certain oddities, and the corkscrew plotlines run rampant with absurdities of their own. Penned by a pair of titans in Jo Swerling and Robert Riskin, The Whole Town’s Talking opens with an inciting incident that’s a true comedic conundrum.

Comic mayhem was always supercharged in the films of the 1930s because the buzz is palpable, the actors are always endowed with certain oddities, and the corkscrew plotlines run rampant with absurdities of their own. Penned by a pair of titans in Jo Swerling and Robert Riskin, The Whole Town’s Talking opens with an inciting incident that’s a true comedic conundrum. Whaddya hear, whaddya say ~ Jimmy Cagney as Rocky Sullivan

Whaddya hear, whaddya say ~ Jimmy Cagney as Rocky Sullivan