It’s a grievous offense, but I must admit to clumping Rhonda Fleming and Arlene Dahl in a category together. They are both redheads of immense beauty, around the same age, and while they both featured in some quality films, they never quite reached the apex of a Maureen O’Hara or a predecessor like Greer Garson. It’s highly unfair I know. Still, in an effort at transparency, it’s inevitably the truth.

However, it’s this very element that makes Slightly Scarlet so enthralling, because it’s as if the very premise is playing with my preconceptions. Maybe I am not the only one who holds these feelings.

Here we have (Arlene Dahl) coming out of prison after serving a stint thanks to some petty jewel thievery. Her big sister (Rhonda Fleming) is there waiting for her as the fawning, motherly figure resolved to keep her wayward sis out of any more trouble.

Together in the frame, bursting with natural color, they fit so exquisitely opposite one another. This alone has intriguing elements to it, but thankfully there is more. Because Slightly Scarlet is also a film belonging to John Payne, director Allan Dwan, and cinematographer John Alton. At 70 years old, Dwan at this point in his career had logged nearly 400 features — an utterly astounding benchmark.

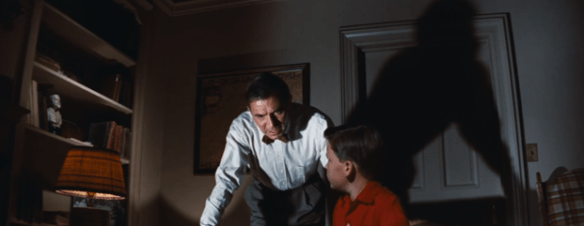

Payne, meanwhile, had forsaken his clean-cut image, working with the likes of Phil Karlson and Dwan to churn out some truly gritty performances. Look up John Alton and you have one of the finest starting points for film noir imagery, period. Even in color, he manages to make it clouded with shadow.

Because Technicolor noir most certainly exists — albeit with lesser frequency — though Slightly Scarlet also has origins in a James M. Cain short story, lending a certain pedigree for sleazy criminals, even if liberties were taken. The picture simultaneously proves worthy company to the ripe feasts of Douglas Sirk and Nicholas Ray from Written in The Wind (1956) to Party Girl (1958). The obvious discordant nature is a draw.

What looks to already be a lurid woman’s picture is met with an undercurrent of political graft and corruption. John Payne is a bit of a hatchet man for a local mobster (Ted de Corsia), integral in influencing all his local operations. He’s derisively nicknamed ‘Genius’ for his shrewd tactics, and yet his boss thinks he will never get on the top of the heap. He’s always out for himself, selfishly.

However, the words prove prophetic as Ben Grace (Payne) all of a sudden does switch sides. Here our narratives get tied together because Ms. Lyons (Fleming) is secretary to up-and-coming mayoral candidate, Frank Jansen (Kent Taylor). Grace is able to supply the dirt to run the gangster Caspar out of town. He’s conveniently found a tape incriminating his former boss in a murder. It’s a surefire way to win an election, and he’s not above such tactics.

The staging is exaggerated from the outset, and the photography is lush — part Technicolor galore the other old tried and true Alton chiaroscuro, which he somehow manages in a entirely color production. At its best, the movie revels in the sordid details and over-the-top theatrics, milking every bit of drama out of the scenario. There’s nothing half-baked or tactful about it. Still, it’s armed with pizzazz aided by a hammy, ever swirling score.

Dahl, playing the sex-crazed klepto of a younger sister, literally gets dragged out of her house for her latest offense. In another scene, when she’s slapped across the face, she simply purrs at the man with beguiling eyes, “You play rough too!” As her latest companion tries to lay his mitts on the goodies inside a safe, Dorothy lounges around the abandoned beach house before setting her sights on a harpoon gun, which she has a frisky bit of fun with. It’s all a gag to her and played against the relentlessly somber, hard-bitten Payne, it only accentuates the inordinate oddities.

While Rhonda Fleming holds down the necessary role as the conflicted central figure and Payne is one of the suppliers of the hard-boiled elements, it is Dahl who titillates and has the most gratifying task as she is given range to be saucy, unhinged, and altogether uninhibited. It fits the scenario.

The subsequent developments are manifold. Mainly that Dorothy starts vying for her sister’s new man, even as she skips out on her therapy sessions. The compulsion to steal exerts itself again with dire consequences, especially in the wake of the political election.

However, as it turns out, Payne is not quite as reformed as he might have led everyone to believe. He’s as pragmatic as he is cynical, getting a ‘Yes Man’ installed as the new city sheriff as he moves in on the mob’s old territory, turning the racket into his own.

Our heroine finds herself utterly conflicted. Between the man she’s fallen for who’s no good — and seems to be in company with her sister — and then the white knight who loves her dearly. The final confrontation, returning to the beach house, does not pull its punches, between spear guns, handguns, and sadistic, even masochistic inflictions of pain.

It’s a fitting shot of volatile adrenaline to cap a movie daring to fluctuate wildly all over the spectrum. It’s not a dignified or a particularly measured effort by any stretch of the imagination, but in pushing its melodramatic tendencies to the max, Slightly Scarlet proves itself more than capable of diverting stretches of crimson entertainment.

3.5/5 Stars

Billy Wilder, more than any screenwriter I’ve ever known, has a knack for voiceover narration. What other novices consider a crutch to feed us information, he uses as an asset to set tone, story, and location, while offsetting the image with the spoken word.

Billy Wilder, more than any screenwriter I’ve ever known, has a knack for voiceover narration. What other novices consider a crutch to feed us information, he uses as an asset to set tone, story, and location, while offsetting the image with the spoken word. The when is 1862. The where is Southern Indiana. We find ourselves in the throes of Quaker country as envisioned by novelist Jessamyn West and brought to the screen by his eminence, William Wyler.

The when is 1862. The where is Southern Indiana. We find ourselves in the throes of Quaker country as envisioned by novelist Jessamyn West and brought to the screen by his eminence, William Wyler. Growing up in a household indebted to British everything, you get accustomed to certain things. Numerous everyday knickknacks and antiques imported from The U.K. Muesli Cereal in the pantry with copious amounts of English Breakfast Tea. Beatrix Potter, P.G. Wodehouse, and Postman Pat become household favorites.

Growing up in a household indebted to British everything, you get accustomed to certain things. Numerous everyday knickknacks and antiques imported from The U.K. Muesli Cereal in the pantry with copious amounts of English Breakfast Tea. Beatrix Potter, P.G. Wodehouse, and Postman Pat become household favorites.

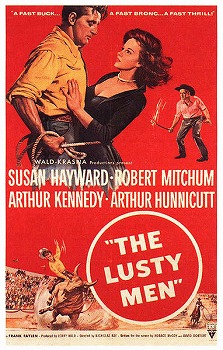

The connotation of the film’s lurid title feels slightly deceptive. Because The Lusty Men might have basic elements of men who desire after women but it’s fairly restrained in this regard. At least more than I initially conceived. However, it is a film characterized by a zeal or a lust for life. The male protagonists are intent or were formerly driven in the pursuit of high living with all the benefit such a life affords.

The connotation of the film’s lurid title feels slightly deceptive. Because The Lusty Men might have basic elements of men who desire after women but it’s fairly restrained in this regard. At least more than I initially conceived. However, it is a film characterized by a zeal or a lust for life. The male protagonists are intent or were formerly driven in the pursuit of high living with all the benefit such a life affords.

I Want to Live! calls upon the words of two men of repute to make an ethos appeal to the audience. The first quotation is plucked from Albert Camus. I’m not sure what the context actually was but the excerpt reads, “What good are films if they do not make us face the realities of our time.” This is followed up by some very official-looking script signed by Edward S. Montgomery, Pulitzer Prize winner, who confirms this is a factual story based on his own journalism and the personal letters of one Barbara Graham.

I Want to Live! calls upon the words of two men of repute to make an ethos appeal to the audience. The first quotation is plucked from Albert Camus. I’m not sure what the context actually was but the excerpt reads, “What good are films if they do not make us face the realities of our time.” This is followed up by some very official-looking script signed by Edward S. Montgomery, Pulitzer Prize winner, who confirms this is a factual story based on his own journalism and the personal letters of one Barbara Graham.