This Land in Mine initiates itself as a memorial to WWI. We see a statue with a crouching soldier. It’s inscribed with the following message: “In memory of those who died to bring peace to the world.” In the foreground, the Nazi juggernaut rolls into town. Peace did not last thanks to Hitler’s voracious appetite for “Lebensraum.”

The juxtaposition is key, and it says everything Renoir wants us to know without putting words to it. A newspaper is strewn on the ground with a very prominent headline featuring Hitler’s latest invasion. We’re seeing it firsthand.

There is only the very beginning, and it suggests something elegant about Renoir’s critique of the Nazis. In his case, it doesn’t come in the guise of a thriller like we might see with Fritz Lang or Hitchcock — this fit their own proclivities and doubled as pulse-pounding entertainment.

For Renoir, the story is a drama of a different sort. The local school is run by only a handful of teachers who must do their best to keep the school of rowdy adolescents afloat even with so many outside distractions. Suddenly Plato’s Republic and Voltaire’s writings are deemed dangerous by the new administration.

The school’s beloved Professor Sorrel (Philip Merivale) muses what the Nazis have before them is a delicate operation — cutting out the heart without killing the patient. Put in such terms, it sounds tenuous at best if not doomed to fail. Something must give way and perish.

The movie’s not about force or sheer strength, but the resoluteness and free reign of ideas. Because this is what brings people together and allows them to think for themselves about the true tenants of good and evil.

The two primary teachers are the middle-aged, ever-reticent Albert Lorry (Charles Laughton), who still lives with his mother, and the fiery soon-to-be-engaged Louise Martin (Maureen O’Hara). They are tasked with “correcting” their textbooks, though Ms. Martin’s act of passive rebellion is to hold on to the miscreant pages for the day they can be pasted back in. If all this sounds harrowing and positively medieval, stinking of Fahrenheit 451, that’s because it does.

Still, we live in a modern society of self-censoring. Not of ourselves mind you, but we like to cut out all the pages of the culture and the world with ideas we don’t find palatable or don’t summarily agree with. It’s so much easier to insulate ourselves with things that are innocuous and inoffensive from our own tribe. Then, as a result, we’re left with an ill-fated and potentially disastrous conception of the world.

This is partially what allows tyrants to take over and also what allows bipartisanism to poison people, since they never see the human being sitting across from them. Does it say something that I often feel less proud of my country than ever before? It’s not so much for the historical sins, because I’ve always known them to be there, but it’s for what feels like our current failures. And not just our failures but the persistent callousness and cynicism pervading our world.

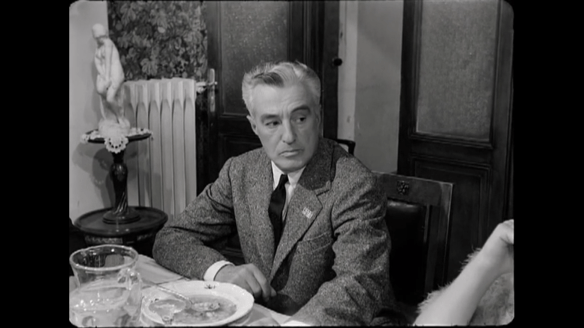

Walter Slezak was always a fine performer in a bevy of roles as diverse as they come. Here his Nazi is in the mold of military efficiency; he’s totally pragmatic — just trying to do his duty and get by. He knows from experience he wants no sabotage and no martyrs. Because this churns up emotions and will blow up like a powder keg.

Later, he preaches how the children of today are the soldiers of tomorrow. No one knows that better than the Nazis with their Hitler youth regimen and indoctrination. But with that, you have the muddied center that a man like George Sanders train station manager must contend with. He lacks the idealism of the academics, namely, his fiancee O’Hara, the principled young woman who gathers the children together to sing rousing songs in the air raid shelter while the Allied bombs fall overhead.

You have this rowdy boy’s hall out of Mr. Chips set against the backdrop of an occupied city during wartime. It makes for a strange marriage but not an inauthentic one. Because, as we’ve already suggested, it’s another crucial battleground for the hearts and minds of the next generation. These are life-altering battles to be fought on their behalf, and it’s not solely with guns and bombs.

Since it has not been mentioned already, This Land is Mine is an unofficial reunion of The Hunchback of Notre Dame and not just the same players. It’s an extension of this same sweet but painful romance as reflected by the bashful Laughton. He has feelings for his young colleague — they care for one another — but she is with another.

Mrs. Lory (Una O’Connor) is a demonstrative lady, with deep-seated opinions, but her maternal love knows no bounds, and it’s phenomenal to watch in action. Her son is imprisoned, no fault of his own. In a world of daily paranoia, he’s one of 10 innocents imprisoned in recompense for two German soldiers murdered in the streets by a saboteur. It’s a debilitating moral dilemma for those who know the perpetrator intimately. After all, it is one life weighed against ten others.

It occurs to me that the man who made Le Grande Illusion could not sell his characters short in time of war. The generation changed and brought with it a new enemy — and we’ve toiled with history to make Hitler and his ilk a different kind of evil — but that almost makes it too easy. We can keep them at arm’s length with a clear conscience.

George Sanders says something telling as he commiserates with the town’s mayor. They are both in undesirable positions of power where they either compromise with the powers that be or fall under fiercer tyranny. Their acquiescing is deemed to be spineless. Sanders retorts:

“It’s easy for people in free countries to call us names, but you wait to see how they behave when the Germans march in. They’ll shake hands. Make the best of it.” A lesser film would have made them mere stooges and collaborators. I made the mistake of believing this was all they were. However, although the moral gradient is quite nuanced, it doesn’t mean Renoir doesn’t have a clear preference.

It comes in the form of Albert, a seemingly diffident man who nevertheless evolves when challenges are thrust upon him. Laughton has every opportunity to save himself quite easily, and yet he resolves to stand for an idea with his fallen friends.

When Laughton gets on the stand and talks about the Nazis’ assault on working-class people, making them into slaves pitted against a middle-class afraid of chaos and disorder, it’s very plainly Renoir’s point of view aided by scribe Dudley Nichols. Truth under any form cannot be allowed to live under the occupation. This is what Laughton stands up for because it is far too precious to go down without a fight.

There’s a lot of rousing defiance in the final act, good for stirring up the patriots, but what did it for me was Laughton’s exit. He gets his kiss and is unceremoniously shoved out of his classroom. But he’s a new man pushing the guards away, hands in pockets, perfectly at peace with the moment. His newfound courage is evident to all.

After watching the film, I had to ask myself the question: If this land is mine — the land I call home — why don’t I start acting like it? It’s so easy to cast aspersions on others and quite another thing to take personal responsibility.

4/5 Stars