Few figures in the West have the mystique in western lore as Billy the Kid, aside from a few prominent names like Wyatt Earp, Butch Cassidy, Jesse James, etc. Billy Joel even famously penned a tune chronicling the life of the outlaw.

Part of the allure, no doubt, has to do with his youth and the casting of the man as a Robin Hood type anti-hero who only robbed those with excess. Inspired by a teleplay by Gore Vidal (who for the record disliked the picture), television-turned-film-director Arthur Penn makes a conscious decision to focus his story on other facets of the character.

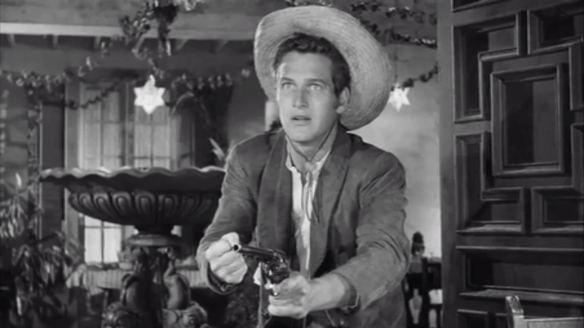

Although slightly older, Paul Newman came into acting about the same time as James Dean and in some respects they were cut out of the same mold. At any rate, they came from a similar school of actors training in the 1950s. Though Newman was no Dean, he does a fine facsimile here. He gives a, at times, disconcerting but overwhelmingly giddy performance as Billy the Kid and somehow his age of 33 doesn’t seem to distract from the part too much. Because he’s still holding onto a decent amount of his boyish charm and good looks.

Leslie Stevens’ script features terse often tiresome colloquial dialogue in a downright peculiarly paced western. However, this is not the main point of interest anyway. For the record, William Bonney (Paul Newman) drifts onto a ranch and is taken on by a trusting cattle rancher John Tunstall (Colin Keith-Johnston). But that same penchant for trust winds up getting him killed in an ambush.

Though he only knew the man for a short period, Billy carries a fierce loyalty and resolves to go after the four men who conspired in killing his boss pulling, his reluctant partners Charlie Bowdre and Tom Folliard into it with him. Allusions to “Through a glass darkly” from Corinthians suggests a bit of the muddled kaleidoscope that the man envisions the world through.

One morning he’s howling with his boys on a wagon heaped with flour, caked in white and the next minute he’s provoking another man to draw on him just so he can blow him away. His old friend, Pat Garrett (John Dehner), has trouble knowing what to do in the face of William’s lighting-hot personality.

The newly minted amnesty in the territory means a temporary peace, instantly obliterated by a moment of stupidity among Billy’s buddies. Though the novels back east have cast him as some fictionalized larger-than-life figure, he’s really nothing like that at all.

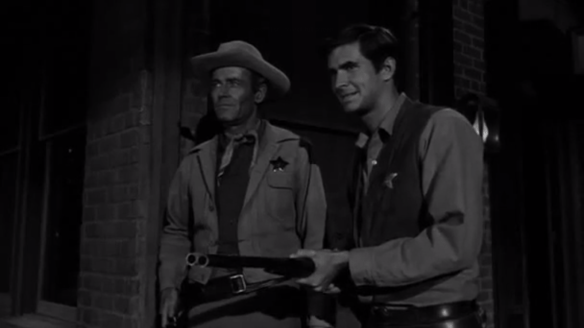

His buddies get it and then as the final straw, Pat vows to hunt down his estranged friend, putting on the badge of the local sheriff, after an unwanted blowup at his own wedding. Billy has alienated the one man who will make him pay. First, he brings him in to be hung and then after the kid escapes, Garrett heads out again to finish things off once. It’s a pitiful character arc and that’s the key.

While it might be overshooting its influence to say that the Left Handed Gun singlehandedly erected a new brand of western, at the very least, it suggested a new age of the West as we knew it. Beyond this, it’s hard not to draw parallels to Penn’s later work in Bonnie and Clyde (1967) which The Left Handed Gun is an obvious precursor to in the depiction of the outsider who uses violence almost indiscriminately.

One scene that leaves an impression involves a blurred image as Billy taunts a deputy from up above, toting a shotgun and blowing him away as he squints through the sunlight. Not only is it composed as a slo-mo killing but as his body lies in the street and people run toward him, instead of screaming, a little girl looks at his solitary boot just sitting there and proceeds to point and laugh. Her mother smacks her but the damage has been done. His death is a joke. There’s no point to it. People fail to react as they have been coached to since the dawning of the cinematic western.

There’s a senselessness to the killing which explodes with an almost haphazard vengeance. In no accordance with reason or morals nor in the end by perceived good or evil. Each bullet is yet another indication of all that is idiosyncratic in the subject matter. Not a hero, not a villain, but a perplexingly near neurotic gunslinger.

Whether it’s to everyone’s taste is another question entirely. It’s more character study than drama and in this close observation, it’s the distillation of a new kind of western hero — the anti-hero, or lack thereof, that is most notable. Today it’s less interesting because we have Peckinpah, Clint Eastwood, and even Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969).

But as a picture going against the grain, an artifact from a certain moment in time, there’s still something burning within its frames. Even if it’s not a fully cohesive effort, The Left Handed Gun is not without its flashes of artfulness and intriguing volatility. It began the work of reconstructing the mythos of the West that had been forged in the movies though there was still a great deal more to come. In fact, Arthur Penn would return to western revisioning with Little Big Man (1970) over a decade later.

3/5 Stars

The proverbial stranger rides into town looking for a place to wash up and grab a bite to eat. We get the sense he might be sticking around. Except, soon enough, he turns right back around and buys a ticket on the first train out of town. Because he has business to attend to.

The proverbial stranger rides into town looking for a place to wash up and grab a bite to eat. We get the sense he might be sticking around. Except, soon enough, he turns right back around and buys a ticket on the first train out of town. Because he has business to attend to.

In Bend of The River, there are glimpses of the man we knew before the war. Joking and smiling with that same face. The affable charm and so on. But it’s also starkly different.

In Bend of The River, there are glimpses of the man we knew before the war. Joking and smiling with that same face. The affable charm and so on. But it’s also starkly different.