I was born and bred a California boy, but there’s a certain something about the girl-next-door. Maybe it’s my midwestern roots, because after all, my mom was born in Iowa before making the move westward.

Anyways, the first time I saw Teresa Wright onscreen I was immediately smitten. She is the complete antithesis of the blatant sexuality of a Marilyn Monroe, a Sophia Loren or Elizabeth Taylor. Granted, all very beautiful women of Hollywood’s Golden Age, but as their predecessor, a very different sort of actress, Wright exudes a certain sweet charm that epitomizes the ideal American girl. Before Donna Reed or Doris Day.

In The Best Years of Our Lives she plays Peggy, the thoughtful, funny and mature daughter of Al and Milly Stephenson. Right from the get go, it’s hard not to love this girl from the quintessential post-war family. She knows how to cook, drives well, has all the skills that are desirable of a lady circa 1946. But the bottom line is her utter sincerity. She seems real.

When she first meets Fred Derry then, there’s no agenda or master plan to seduce him or make him fall in love with her. It just happens. She doesn’t quite want it to happen and she tries to resist the urges. She’s not prone to drama. She’s above that kind of behavior. In other words, she’s a real winner.

Thus, the moment when she begins to fall for a married man, unhappily married, our heart aches for her–at least that’s what I felt, because she deserves to be happy. How could Teresa Wright not be happy? And in the end she gets the ending that she deserves–the one we want for her and Fred.

The legendary critic James Agee wrote this of her performance:

“This new performance of hers, entirely lacking in big scenes, tricks, or obstreperousness—one can hardly think of it as acting—seems to me one of the wisest and most beautiful pieces of work I have seen in years. If the picture had none of the hundreds of other things it has to recommend it, I could watch it a dozen times over for that personality and its mastery alone.”

Took the words right out of my mouth J.A.

And beyond simply this film, there was a string of equally amiable performances that came before and after. She’s the sweet innocent ingenue in The Little Foxes and Mrs. Miniver. In The Pride of the Yankees she was the perfect incarnation of Lou Gehrig’s faithful wife, while also playing the intrepid “Charlie” in Hitchcock’s home thriller Shadow of a Doubt. Later on in her career she would star in the psychological western Pursued and opposite Marlon Brando in The Men.

Perhaps the roles share a degree of similarity, but it should not go unnoticed that Teresa Wright had a string of three academy award nominations, that suggest that she was a pretty big deal in her day. To this day, no one has equaled that feat of hers.

But why had I never heard of this wonderful, pure actress until so much later in my cinematic odyssey? She had slipped through the cracks and crevices of my film education. And that might best be explained by Teresa Wright’s own words:

“I’m just not the glamour type. Glamour girls are born, not made. And the real ones can be glamorous even if they don’t wear magnificent clothes. I’ll bet Lana Turner would look glamorous in anything.”

“The type of contract between players and producers is, I feel, antiquated in form and abstract in concept. We have no privacies which producers cannot invade, they trade us like cattle, boss us like children.” – (Wright would not allow herself to be shot in certain manners for publicity photos and ultimately lost her contract with Samuel Goldwyn)

“I only ever wanted to be an actress, not a star.”

So certainly this girl was not your typical Hollywood movie star. She lacks flamboyance and your typical glamour, but she makes up with it by being a deeply heartfelt and sincere individual onscreen. She feels real and in her earliest roles, completely innocent. It’s hard not to fall head over heals for a girl like that.

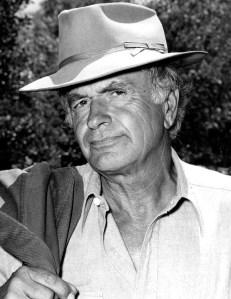

“I don’t like anybody pushing me around. I don’t like anybody pushing you around. I don’t like anybody getting pushed around.” Van Heflin as Sam Masterson

“I don’t like anybody pushing me around. I don’t like anybody pushing you around. I don’t like anybody getting pushed around.” Van Heflin as Sam Masterson 17 or 18 years later a full-grown Sam Masterson (Van Heflin) decides to return to his old stomping grounds, Iverstown, on a whim. He’s surprised to learn that the “little scared boy on Sycamore street” is now District Attorney (Kirk Douglas). And he’s now married to Martha Ivers (Stanwyck). She and Sam had something going long ago, but he’s all but forgotten it by now. He’s made a living as a gambler who has a pretty handy dandy coin trick, but really Heflin’s character could be anything.

17 or 18 years later a full-grown Sam Masterson (Van Heflin) decides to return to his old stomping grounds, Iverstown, on a whim. He’s surprised to learn that the “little scared boy on Sycamore street” is now District Attorney (Kirk Douglas). And he’s now married to Martha Ivers (Stanwyck). She and Sam had something going long ago, but he’s all but forgotten it by now. He’s made a living as a gambler who has a pretty handy dandy coin trick, but really Heflin’s character could be anything. We don’t actually see Barbara Stanwyck’s face until 30 minutes into the film, but it doesn’t matter. She as well as

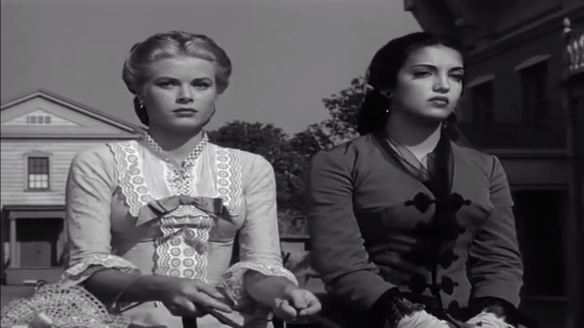

We don’t actually see Barbara Stanwyck’s face until 30 minutes into the film, but it doesn’t matter. She as well as  Honestly, although Stanwyck is our leading lady, it’s quite difficult to decide whose film this really is. Van Heflin and Barbara Stanwyck are at its core, but then again, Scott and Douglas do a fine job trying to upstage them. There’s a polarity in the main players, meaning Stanwyck and Heflin have the power, and the other two are the subservient man and woman respectively. However, the film really becomes a constant tug-of-war. Douglas is not just a spineless alcoholic. There’s an edge to him. Scott seems like a softy and yet there’s an incongruity between her persona and that prison rap that hangs over her. Heflin seems like the one relatively straight arrow because as we find out, Stanwyck is fairly disturbed. She’s no Phyllis Dietrichson and that becomes evident in yet another climatic conflict involving a gun. But she’s still demented, just in a different way.

Honestly, although Stanwyck is our leading lady, it’s quite difficult to decide whose film this really is. Van Heflin and Barbara Stanwyck are at its core, but then again, Scott and Douglas do a fine job trying to upstage them. There’s a polarity in the main players, meaning Stanwyck and Heflin have the power, and the other two are the subservient man and woman respectively. However, the film really becomes a constant tug-of-war. Douglas is not just a spineless alcoholic. There’s an edge to him. Scott seems like a softy and yet there’s an incongruity between her persona and that prison rap that hangs over her. Heflin seems like the one relatively straight arrow because as we find out, Stanwyck is fairly disturbed. She’s no Phyllis Dietrichson and that becomes evident in yet another climatic conflict involving a gun. But she’s still demented, just in a different way.