“You’re living at home. Is that right?

“You’re living at home. Is that right?

Yes.

Do you know what you’re going to do?

No.

Are you going to graduate school?

No.” ~ Elaine Robinson to Benjamin Braddock

As a recently graduated person, I thought it was only pertinent to return to this landmark film to see if I could glean any new insight. In many ways, the main premise of The Graduate always repulsed me. I couldn’t get behind the comedy because it seemed so at odds with what is going on onscreen.

But now I think I more fully understand Mike Nichols’ style as he leads us through Buck Henry’s script. There certainly is a wicked wit dwelling there, but there’s also more to it. He’s trying to undermine social mores and say something by switching tones on us. In this case, it seems like he’s talking to all those listless souls just set adrift after college. He was their elder, but in the characters of Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) and some respects Elaine Robinson (Katherine Ross), young people found their equals. People they could relate to in their own anxiety and at times apathy about the future. And it’s as much Elaine’s story as it is Ben’s since they both are riding off into the great unknown of their future together.

Thus, this isn’t just about an affair, though that did help to shatter the Production Codes. There is so much more that actually causes Benjamin to get involved with Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft). The implications extend far beyond.While The Graduate‘s main hook seems rather curious, the rest isn’t all that crazy. In fact, it’s quite relatable.

We get our first view of Ben, sullen and anxious as he rides the moving walkway in the airport terminal. The haunting vocals of Simon & Garfunkel’s “Sound of Silence” ring in our ears, but there’s also that almost comical voice reminding travelers to use the handrails.

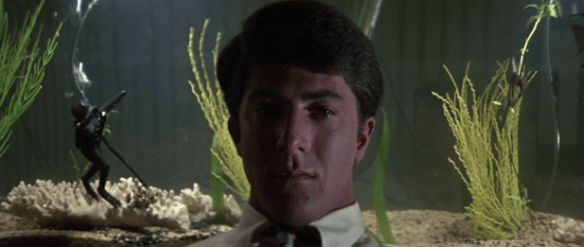

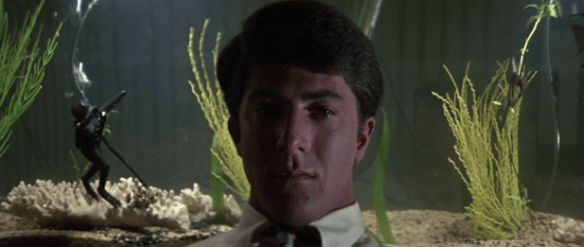

It’s when he touches down and gets home that things become all too real. He’s entering back into his parent’s world which is reinforced by this general theme of suffocation and in some sense alienation, fawned over by parent’s friends and encased in a scuba suit. Ironically, he’s no hippie or counter-cultural revolutionary, but he still feels at odds with the community he finds himself in. There’s a generational gap, and even Hoffman’s own portrayal is so contrary to this WASP society. In casting Hoffman, not a particularly handsome young man, an atypical example, Nichols is ratcheting up the irony.

Then Mrs. Robinson coolly enters his life. It’s perhaps best signified when she tosses him the keys. They end up in the fish tank almost as if on purpose and after that she has him reeling for good. Soon he’s walking into the lion’s den (or lioness’s) as she expertly manipulates and elicits the precise response from him. In these moments the film is elevated by the awkward, huffing and puffing, and nervous chattering of Hoffman. We often forget the second part of his famed line, “Mrs. Robinson you’re trying to seduce me. Aren’t you?” His general naivete and hesitancy say it all.

Then Mrs. Robinson coolly enters his life. It’s perhaps best signified when she tosses him the keys. They end up in the fish tank almost as if on purpose and after that she has him reeling for good. Soon he’s walking into the lion’s den (or lioness’s) as she expertly manipulates and elicits the precise response from him. In these moments the film is elevated by the awkward, huffing and puffing, and nervous chattering of Hoffman. We often forget the second part of his famed line, “Mrs. Robinson you’re trying to seduce me. Aren’t you?” His general naivete and hesitancy say it all.

I also made a startling discovery. Ben doesn’t have any friends! Or else, where are they? The inference perhaps being that he spent so much time being a track star, being on the debate team, and being editor of the paper that he never stopped to do the other things that college is all about. Building relationships with other human beings your own age. When he gets out and realizes his directionless anxiety, he tries to remedy it in other ways. The most obvious way is sleeping with Mrs. Robinson.

But when he meets Elaine Robinson and finally begins to connect with her on a peer-to-peer level, it’s something so profound to him. Having someone his own age that he can relate to, who feels the same unnamed apprehension and angst that strains on him. It’s what makes Ben become so mixed up. He has true feelings for her, while his affair with Mrs. Robinson only serves to poison all that could be good. And his illogical, unhealthy pursuit of Elaine continues to Berkeley where she is attending school. Still, Mrs. Robinson and her now estranged husband look to send their precious daughter far away from Benjamin Braddock.

But when he meets Elaine Robinson and finally begins to connect with her on a peer-to-peer level, it’s something so profound to him. Having someone his own age that he can relate to, who feels the same unnamed apprehension and angst that strains on him. It’s what makes Ben become so mixed up. He has true feelings for her, while his affair with Mrs. Robinson only serves to poison all that could be good. And his illogical, unhealthy pursuit of Elaine continues to Berkeley where she is attending school. Still, Mrs. Robinson and her now estranged husband look to send their precious daughter far away from Benjamin Braddock.

That’s what makes his final Herculean effort all the more climactic. He bursts in on her marriage to another man and whisks her off to another life altogether. A life that seems exciting at first, because, oh how great it is to be young and in love. But once they climb aboard that bus in their tattered garments, have a chance to sit down and really think about what they are embarking on, you see something else in their eyes. The laughter slowly dissipates and as they look around nervously, they begin to somber up. True, Ben is no longer alone in an airport terminal, he has a fellow traveler, but that does not make the future any less unpredictable or scary for that matter.

That’s what makes his final Herculean effort all the more climactic. He bursts in on her marriage to another man and whisks her off to another life altogether. A life that seems exciting at first, because, oh how great it is to be young and in love. But once they climb aboard that bus in their tattered garments, have a chance to sit down and really think about what they are embarking on, you see something else in their eyes. The laughter slowly dissipates and as they look around nervously, they begin to somber up. True, Ben is no longer alone in an airport terminal, he has a fellow traveler, but that does not make the future any less unpredictable or scary for that matter.

That is the life of a graduate. In so many ways feeling like an outsider, a foreigner in a land that you used to know. You’re living at home. You don’t know what you’re going to do and you’re not going to put off the decision by going to grad school. We’ve all been in a similar place one time or another and that’s why this film resonates, not only with the generations of the 1960s but even to this day.

What truly elevates The Graduate above Nichols’ other films, aside from this universal quality, is the stellar soundtrack courtesy of fellow New York natives Simon & Garfunkel, who became icons of the folk scene during the 60s and 70s. Their album Bookends is still a classic, featuring the fully polished version of “Mrs. Robinson.” While not all the lyrics are here in the film, it became an anthem, reflecting the gap created between the older generations and their kin. While the likes of “Sound of Silence,” “April Come She Will,” and “Scarborough Fair” lend themselves to the more introspective moments of the film like no score ever could. It’s part of what makes The Graduate a cinematic watershed of the 1960s.

4.5/5 Stars

Sometimes you attempt to make a mental pros and cons list to try and convince yourself in one direction or the other after watching something. Copenhagen was such a film for me. Bike rides through the city. Pro. At times this film loses its steam and flounders a bit. Con.

Sometimes you attempt to make a mental pros and cons list to try and convince yourself in one direction or the other after watching something. Copenhagen was such a film for me. Bike rides through the city. Pro. At times this film loses its steam and flounders a bit. Con.

“You’re living at home. Is that right?

“You’re living at home. Is that right? Then Mrs. Robinson coolly enters his life. It’s perhaps best signified when she tosses him the keys. They end up in the fish tank almost as if on purpose and after that she has him reeling for good. Soon he’s walking into the lion’s den (or lioness’s) as she expertly manipulates and elicits the precise response from him. In these moments the film is elevated by the awkward, huffing and puffing, and nervous chattering of Hoffman. We often forget the second part of his famed line, “Mrs. Robinson you’re trying to seduce me. Aren’t you?” His general naivete and hesitancy say it all.

Then Mrs. Robinson coolly enters his life. It’s perhaps best signified when she tosses him the keys. They end up in the fish tank almost as if on purpose and after that she has him reeling for good. Soon he’s walking into the lion’s den (or lioness’s) as she expertly manipulates and elicits the precise response from him. In these moments the film is elevated by the awkward, huffing and puffing, and nervous chattering of Hoffman. We often forget the second part of his famed line, “Mrs. Robinson you’re trying to seduce me. Aren’t you?” His general naivete and hesitancy say it all. But when he meets Elaine Robinson and finally begins to connect with her on a peer-to-peer level, it’s something so profound to him. Having someone his own age that he can relate to, who feels the same unnamed apprehension and angst that strains on him. It’s what makes Ben become so mixed up. He has true feelings for her, while his affair with Mrs. Robinson only serves to poison all that could be good. And his illogical, unhealthy pursuit of Elaine continues to Berkeley where she is attending school. Still, Mrs. Robinson and her now estranged husband look to send their precious daughter far away from Benjamin Braddock.

But when he meets Elaine Robinson and finally begins to connect with her on a peer-to-peer level, it’s something so profound to him. Having someone his own age that he can relate to, who feels the same unnamed apprehension and angst that strains on him. It’s what makes Ben become so mixed up. He has true feelings for her, while his affair with Mrs. Robinson only serves to poison all that could be good. And his illogical, unhealthy pursuit of Elaine continues to Berkeley where she is attending school. Still, Mrs. Robinson and her now estranged husband look to send their precious daughter far away from Benjamin Braddock. That’s what makes his final Herculean effort all the more climactic. He bursts in on her marriage to another man and whisks her off to another life altogether. A life that seems exciting at first, because, oh how great it is to be young and in love. But once they climb aboard that bus in their tattered garments, have a chance to sit down and really think about what they are embarking on, you see something else in their eyes. The laughter slowly dissipates and as they look around nervously, they begin to somber up. True, Ben is no longer alone in an airport terminal, he has a fellow traveler, but that does not make the future any less unpredictable or scary for that matter.

That’s what makes his final Herculean effort all the more climactic. He bursts in on her marriage to another man and whisks her off to another life altogether. A life that seems exciting at first, because, oh how great it is to be young and in love. But once they climb aboard that bus in their tattered garments, have a chance to sit down and really think about what they are embarking on, you see something else in their eyes. The laughter slowly dissipates and as they look around nervously, they begin to somber up. True, Ben is no longer alone in an airport terminal, he has a fellow traveler, but that does not make the future any less unpredictable or scary for that matter. Robert Mulligan is an unassuming film director. Man in the Moon would be his last film in a career that was not so much illustrious as it was respectable. In truth, I’ve only had the pleasure of seeing one of his other films — his crowning achievement To Kill a Mockingbird.

Robert Mulligan is an unassuming film director. Man in the Moon would be his last film in a career that was not so much illustrious as it was respectable. In truth, I’ve only had the pleasure of seeing one of his other films — his crowning achievement To Kill a Mockingbird. Arguably, the next most important character in Dani’s story is Court (Jason London). They have your typical terse meet-cute that signifies only one thing. They must fall in love. It turns out he’s the eldest son of an old friend of Mrs. Trant. Soon things change for young Dani because she’s never known someone like Court, much less liked a boy.

Arguably, the next most important character in Dani’s story is Court (Jason London). They have your typical terse meet-cute that signifies only one thing. They must fall in love. It turns out he’s the eldest son of an old friend of Mrs. Trant. Soon things change for young Dani because she’s never known someone like Court, much less liked a boy. The second half of the film enters melodramatic territory that first hits the Trant’s with familial turmoil, and then Court. Dani for the first time in her life is faced with the full brunt of tribulation. What makes matter worse is her feelings are all mixed up. She loves her sister. She hates her sister. She cannot bear to see Court. She cannot bear the suffering. It’s in these moments that uncomfortable feeling well up in the pit of your stomach.

The second half of the film enters melodramatic territory that first hits the Trant’s with familial turmoil, and then Court. Dani for the first time in her life is faced with the full brunt of tribulation. What makes matter worse is her feelings are all mixed up. She loves her sister. She hates her sister. She cannot bear to see Court. She cannot bear the suffering. It’s in these moments that uncomfortable feeling well up in the pit of your stomach.

It never feels flashy or superficial in these crucial moments. Any slick plot device or cinematic allusion falls away to get at the heart and soul of this film. It’s about coping with death and finding closure in that terrible event in life. Specifically for this one young man, but it is universally applicable to most every one of us. Especially when you’re young because as young, naive individuals, death can feel like such a foreign adversary. It’s so far removed from our sensibilities, and that’s what makes it so painfully unnatural when it strikes. In many ways, Greg is our surrogate. For all those who struggled to find themselves in high school, or college, or even life in general. And for all of those, who took risks on friendship in a world full of death and dying. Once more Me & Earl and the Dying Girl proved its worth, not by being a perfect film, but by being a heartfelt one.

It never feels flashy or superficial in these crucial moments. Any slick plot device or cinematic allusion falls away to get at the heart and soul of this film. It’s about coping with death and finding closure in that terrible event in life. Specifically for this one young man, but it is universally applicable to most every one of us. Especially when you’re young because as young, naive individuals, death can feel like such a foreign adversary. It’s so far removed from our sensibilities, and that’s what makes it so painfully unnatural when it strikes. In many ways, Greg is our surrogate. For all those who struggled to find themselves in high school, or college, or even life in general. And for all of those, who took risks on friendship in a world full of death and dying. Once more Me & Earl and the Dying Girl proved its worth, not by being a perfect film, but by being a heartfelt one.