Fritz Lang’s archetypal sci-fi epic is steeped in politics, religion, and humanity, but above all, it is a true cinematic experience. It is visually arresting, and it still causes us to marvel with set-pieces that remain extraordinary. How did Fritz Lang piece together such a gargantuan accomplishment? Maybe even equally extraordinary, how was I able to see almost a complete cut of this film, which was at different times thought to be lost, incomplete, and ruined?

Fritz Lang’s archetypal sci-fi epic is steeped in politics, religion, and humanity, but above all, it is a true cinematic experience. It is visually arresting, and it still causes us to marvel with set-pieces that remain extraordinary. How did Fritz Lang piece together such a gargantuan accomplishment? Maybe even equally extraordinary, how was I able to see almost a complete cut of this film, which was at different times thought to be lost, incomplete, and ruined?

Metropolis really feels like one of the earliest blockbusters, although I would have to further substantiate that. Still, it’s basic story is generally captivating following a young man named Freder from the upper echelon of society with a father who runs things. This young man is really in the perfect position to succeed, the way society is set up. He even goes to the preeminent school where all the boys are dressed in white. Little does he know in the lower depths the beleaguered, grungy, weary masses in black are slowly killing themselves with work. The machine that drives this society is never satisfied, always desiring to be fed more and more and more.

When the boy finally sees the reality of the infrastructure his paradise is built upon, he cries out in horror. This is not the way things are supposed to be. He eventually switches places with one of these workers and attends a meeting deep in the catacombs (an allusion to the early Christians), where the pure goddess Maria lifts the spirits of her fellow man. But of course, the evil inventor Rotwang is enlisted by Freder’s father Joh Frederson. Their own relationship is marred by conflict over a woman they both loved. Freder’s dead mother. And so the scientist looks to resurrect his long lost love, and he needs Maria to develop his plan. He kidnaps her and from her likeness creates a double, who goes out to wreak havoc on all of Metropolis. The apocalyptic words of the Book of Revelation ring true as the whore of Babylon deceives the masses and leads them to destruction.

But Freder is the Mediator, he is the Savior of his people, and he is necessary to bring peace and tranquility to a world that has descended into such brokenness. So Metropolis is certainly a film full of symbolic touches, religious connotations, and political commentary, but all of this is developed by Fritz Lang through an archetypal hero’s narrative.

Hollywood has become an industry seemingly so obsessed with story, screenplays, plots. Certainly, a film like Metropolis is at least adequate in that area alone, but what really sets a film such as this apart is its cinematic scope. The sheer vast expanses it fills. The scope it creates through its plethora of extras and encompassing sets is hard to downplay. How to describe scenes where water is literally breaking down walls and covering masses of fleeing children? Or smokestacks spewing out refuse while trains, planes, and automobiles pass by in every direction. People scattering this way and that, following the false Maria in a chaotic frenzy. It reminds us what the motion picture, the moving picture, is all about. The images that are brought before us lead to a suspension of disbelief because more importantly they are incredibly affecting. At the atypical 20 frames per second, they are images full of tension, full of energy, and full of life.

In a sense, with Metropolis, we can easily see a precursor to Chaplin’s Modern Times a decade later. There is a general apprehension of the machine and the impact of a true industrial revolution. There is a fear that there are more positives than negatives. That machines will take over and man will become outdated. Perhaps someday our creation will destroy us. By today’s standards, such notions seem archaic, but are they? We still live in a society ever more obsessed with advancement, technology, and all the things that come with that. However outdated some of Metropolis might feel, and there are numerous such moments, at its core is the final resolution that between the body and the mind there must be a heart to regulate. We are not simply animals with bodies or rational machines with minds, but the beauty of humanity is that we have a heart, pulsing with life and vitality. That is something to be grateful for and never lose sight of.

In a sense, with Metropolis, we can easily see a precursor to Chaplin’s Modern Times a decade later. There is a general apprehension of the machine and the impact of a true industrial revolution. There is a fear that there are more positives than negatives. That machines will take over and man will become outdated. Perhaps someday our creation will destroy us. By today’s standards, such notions seem archaic, but are they? We still live in a society ever more obsessed with advancement, technology, and all the things that come with that. However outdated some of Metropolis might feel, and there are numerous such moments, at its core is the final resolution that between the body and the mind there must be a heart to regulate. We are not simply animals with bodies or rational machines with minds, but the beauty of humanity is that we have a heart, pulsing with life and vitality. That is something to be grateful for and never lose sight of.

5/5 Stars

Disney has scored again. On almost all accounts Zootopia is grade-A family entertainment. To address the elephant in the room, the film is rather formulaic in its hero’s journey and at times it feels like we are attempting to systematically check off all the necessary moments in the rise, fall, and redemption of our spunky heroine. However, there are moments of wit and grace that begin to slowly grab hold of us an audience. It, in turn, becomes ceaselessly inventive with this metropolis of anthropomorphic animals, whether it is the rhythms of daily life or the social issues present that look strangely familiar.

Disney has scored again. On almost all accounts Zootopia is grade-A family entertainment. To address the elephant in the room, the film is rather formulaic in its hero’s journey and at times it feels like we are attempting to systematically check off all the necessary moments in the rise, fall, and redemption of our spunky heroine. However, there are moments of wit and grace that begin to slowly grab hold of us an audience. It, in turn, becomes ceaselessly inventive with this metropolis of anthropomorphic animals, whether it is the rhythms of daily life or the social issues present that look strangely familiar.

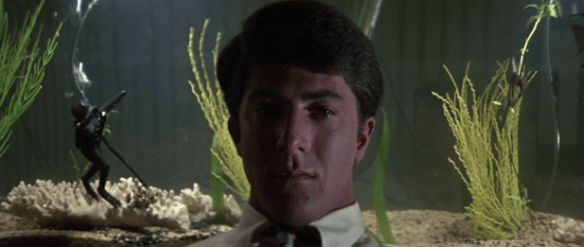

“You’re living at home. Is that right?

“You’re living at home. Is that right? Then Mrs. Robinson coolly enters his life. It’s perhaps best signified when she tosses him the keys. They end up in the fish tank almost as if on purpose and after that she has him reeling for good. Soon he’s walking into the lion’s den (or lioness’s) as she expertly manipulates and elicits the precise response from him. In these moments the film is elevated by the awkward, huffing and puffing, and nervous chattering of Hoffman. We often forget the second part of his famed line, “Mrs. Robinson you’re trying to seduce me. Aren’t you?” His general naivete and hesitancy say it all.

Then Mrs. Robinson coolly enters his life. It’s perhaps best signified when she tosses him the keys. They end up in the fish tank almost as if on purpose and after that she has him reeling for good. Soon he’s walking into the lion’s den (or lioness’s) as she expertly manipulates and elicits the precise response from him. In these moments the film is elevated by the awkward, huffing and puffing, and nervous chattering of Hoffman. We often forget the second part of his famed line, “Mrs. Robinson you’re trying to seduce me. Aren’t you?” His general naivete and hesitancy say it all. But when he meets Elaine Robinson and finally begins to connect with her on a peer-to-peer level, it’s something so profound to him. Having someone his own age that he can relate to, who feels the same unnamed apprehension and angst that strains on him. It’s what makes Ben become so mixed up. He has true feelings for her, while his affair with Mrs. Robinson only serves to poison all that could be good. And his illogical, unhealthy pursuit of Elaine continues to Berkeley where she is attending school. Still, Mrs. Robinson and her now estranged husband look to send their precious daughter far away from Benjamin Braddock.

But when he meets Elaine Robinson and finally begins to connect with her on a peer-to-peer level, it’s something so profound to him. Having someone his own age that he can relate to, who feels the same unnamed apprehension and angst that strains on him. It’s what makes Ben become so mixed up. He has true feelings for her, while his affair with Mrs. Robinson only serves to poison all that could be good. And his illogical, unhealthy pursuit of Elaine continues to Berkeley where she is attending school. Still, Mrs. Robinson and her now estranged husband look to send their precious daughter far away from Benjamin Braddock. That’s what makes his final Herculean effort all the more climactic. He bursts in on her marriage to another man and whisks her off to another life altogether. A life that seems exciting at first, because, oh how great it is to be young and in love. But once they climb aboard that bus in their tattered garments, have a chance to sit down and really think about what they are embarking on, you see something else in their eyes. The laughter slowly dissipates and as they look around nervously, they begin to somber up. True, Ben is no longer alone in an airport terminal, he has a fellow traveler, but that does not make the future any less unpredictable or scary for that matter.

That’s what makes his final Herculean effort all the more climactic. He bursts in on her marriage to another man and whisks her off to another life altogether. A life that seems exciting at first, because, oh how great it is to be young and in love. But once they climb aboard that bus in their tattered garments, have a chance to sit down and really think about what they are embarking on, you see something else in their eyes. The laughter slowly dissipates and as they look around nervously, they begin to somber up. True, Ben is no longer alone in an airport terminal, he has a fellow traveler, but that does not make the future any less unpredictable or scary for that matter.

Of course, her first customer happens to be a police chief named Griff (Anthony Eisley), who advises her to skedaddle out of town as quick as possible. He gives her the details on a cozy joint across the border known for their Bonbon girls. He thinks he’s got her pegged, but Kelly goes and does something even he wouldn’t expect.

Of course, her first customer happens to be a police chief named Griff (Anthony Eisley), who advises her to skedaddle out of town as quick as possible. He gives her the details on a cozy joint across the border known for their Bonbon girls. He thinks he’s got her pegged, but Kelly goes and does something even he wouldn’t expect. The social commentary is there. The characters are interesting. Meanwhile, Fuller slices and dices through taboo subjects that would have horrified censors and yet he brings them to the forefront in such a way that hardly glorifies them, but actually gets them out in the open. Every detail isn’t written out, but Fuller throws us into the narrative and allows us to track with him. He puts a little faith in his audience.

The social commentary is there. The characters are interesting. Meanwhile, Fuller slices and dices through taboo subjects that would have horrified censors and yet he brings them to the forefront in such a way that hardly glorifies them, but actually gets them out in the open. Every detail isn’t written out, but Fuller throws us into the narrative and allows us to track with him. He puts a little faith in his audience. “This long corridor is the magic highway to the Pulitzer Prize” – Johnny Barrett

“This long corridor is the magic highway to the Pulitzer Prize” – Johnny Barrett Behind the pearly gates, there are brawls galore and noisy neighbors riddled with all sorts of neurosis, quirks, and ticks. There are the good cop and bad cop who help care for the patients and keep them at bay. Johnny even begins to have hallucinations of his girlfriend drifting through his dreams. He gets introduced to hydrotherapy, dance therapy, and even faces a traumatizing experience at the hands of women in the female ward.

Behind the pearly gates, there are brawls galore and noisy neighbors riddled with all sorts of neurosis, quirks, and ticks. There are the good cop and bad cop who help care for the patients and keep them at bay. Johnny even begins to have hallucinations of his girlfriend drifting through his dreams. He gets introduced to hydrotherapy, dance therapy, and even faces a traumatizing experience at the hands of women in the female ward. The boisterous, tumultuous chaos of the ward does almost become maddening, even to the viewer. Johnny has a few angry outbursts of his own as the strain of the facility gets to him more and more every day. Electric shock therapy among the other treatments leaves him mixed-up, confused, and overtly paranoid. He’s hardly the man we met in that office so many days ago and even if he got the scoop he was looking for, at what cost? Shock Corridor has a thunderously disconcerting ending worthy of a Fuller production.

The boisterous, tumultuous chaos of the ward does almost become maddening, even to the viewer. Johnny has a few angry outbursts of his own as the strain of the facility gets to him more and more every day. Electric shock therapy among the other treatments leaves him mixed-up, confused, and overtly paranoid. He’s hardly the man we met in that office so many days ago and even if he got the scoop he was looking for, at what cost? Shock Corridor has a thunderously disconcerting ending worthy of a Fuller production. “What a fouled-up outfit I got myself into” – Sgt. Zack

“What a fouled-up outfit I got myself into” – Sgt. Zack But the old WWII vet simply acknowledges the facts and retorts with his own piece of trivia. In the all Japanese-American regiment the 442nd 3,000 Nisei “idiots” got the purple heart for bravery. All he knows is that he’s an American no matter how he’s treated. That doesn’t change. Once more Fuller delivers some of the most engaging portrayals of Asian characters ever and the discussions of race relations were way ahead of their time. Both Richard Loo and James Edwards are honorable characters who hardly fall into any common stereotype.

But the old WWII vet simply acknowledges the facts and retorts with his own piece of trivia. In the all Japanese-American regiment the 442nd 3,000 Nisei “idiots” got the purple heart for bravery. All he knows is that he’s an American no matter how he’s treated. That doesn’t change. Once more Fuller delivers some of the most engaging portrayals of Asian characters ever and the discussions of race relations were way ahead of their time. Both Richard Loo and James Edwards are honorable characters who hardly fall into any common stereotype.