Since my time living in Tokyo, I’ve continued to be fascinated with how Japanese culture will create these hyper-specific niches of popular fandom. Japanese people take their hobbies very seriously and they go all in. You often meet teenagers or straight-laced salarymen who can barely string together sentences in English, only to discover they have some unique knowledge about American culture, especially in the realm of music.

Since my time living in Tokyo, I’ve continued to be fascinated with how Japanese culture will create these hyper-specific niches of popular fandom. Japanese people take their hobbies very seriously and they go all in. You often meet teenagers or straight-laced salarymen who can barely string together sentences in English, only to discover they have some unique knowledge about American culture, especially in the realm of music.

There was a businessman who loved Olivia Newton-John; his go-to English-language Karaoke song was “Physical.” There was a student who jammed out to Korn, or one of my fellow teachers who shared a love of Sam Cooke and taught me about jazz musicians like John Coltrane and Charlie Parker.

Japanese popular culture was arguably at its height during the 1980s. You had the economic miracle or the “bubble,” which led to unprecedented prosperity in the country and with it greater disposable income and thriving youth subcultures.

Tokyo Pop feels like a perfect time capsule for this precise moment. There are evocations of pop culture that blend Japanese tradition with Western influence. Front and center are a Mickey Mouse ryokan in Iidabashi, then iconic brands like KFC, McDonalds, and Dunkin Donuts.

There were even a couple of times I sat up in my seat because I felt like I knew where a storefront or restaurant might be below the neon lights of the city. However, some of the most famous landmarks are unmistakable. We get views of Shibuya near the Hachiko statue or greasers and punks hanging out in Harajuku near Yoyogi Park.

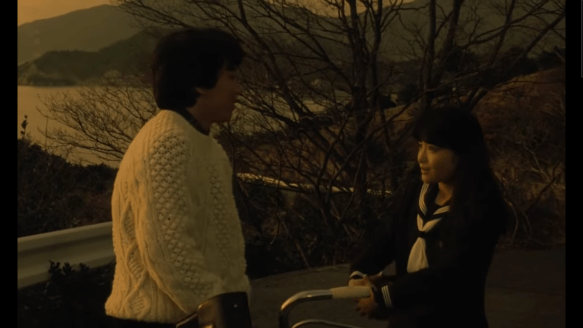

I don’t need much plot to enjoy the movie, but here it is. Wendy Reed (Carrie Hamilton) isn’t having much luck on the music circuit in America. When she receives a postcard from a friend, plastered with Mount Fuji on the front, she makes the impetuous decision to make the trip. However, she arrives only to realize her girlfriend has already moved on.

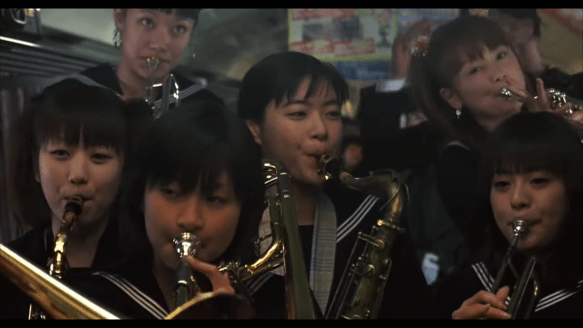

So she’s left high and dry bumming around Tokyo like a helpless baby who doesn’t know the culture, can’t speak the language, and is quickly running out of money. Hiro Yamaguchi (Diamond Yukai) spies her at a street vendor where he’s eating late at night with his buddies, and they bet him that he can’t get lucky with her. He takes them on. It’s a trifle, a cliché-filled scenario, but it’s easy to excuse the film based on what it excels at.

Carrie Hamilton and Yutaka “Diamond” Yukai try and go through the paces of antagonism, however, it’s their genuine camaraderie and shared appreciation of music that really shines through. In one sequence he serenades his American flame with an acoustic rendition of “You Make Me Feel Like a Natural Woman.”

Meanwhile, his band spends their time trying to get to a prominent Tokyo tastemaker named Doda who can make or break their careers. When all their ploys fail, Wendy finally takes the very direct approach waltzing into his office and commanding the room.

Eventually they make it big playing poppy covers of “Blue Suede Shoes” and “Do You Believe in Magic.” We see their rapid ascension as media personalities and global sensations, but at what cost? The couple’s able to get their own apartment and they should be happy, but their art suffers. They’ve pigeonholed themselves doing something that isn’t life-giving. They want to rock out.

Tokyo Pop‘s alive with so much youthful energy and, I would argue it has an even more perceptive viewpoint than later works like Lost in Translation. Although it has an entry point for American audiences, so much of it feels attuned to aspects of Japanese culture; they’re the type of moments I see and totally recognize, not as foreign and other, but authentic.

Japanese lavishing effusive praise on their fellow countrymen for any nominal use of English. Shoes taken off at the entryway. Every taxi driver’s fear of foreigners. Karaoke and alcohol as one of the most beloved forms of socialization, and the kindness of elderly men and women who will walk you where you need to go in spite of any language barrier.

In its day, Fran Rubel Kuzui’s movie was quite a success at Cannes only to fall away thanks to a distributor that went defunct. For a film that’s so perfectly in my wheelhouse, it’s a joy to see it resurrected from obscurity in a fancy new print that does wonders in making the images of the 1980s explode off the screen. There’s a tactile sense that we are there in the moment.

During an interview, the director acknowledged, only years later when friends told her, that she and her Japanese husband Kaz Kuzui were basically Wendy and Hiro. If not in actuality, then certainly it mirrors how their relationship crossed cultural bounds.

It’s also easy to draw parallels between Tokyo Pop and Lost in Translation for how they capture a moment in time (and coincidentally they both feature Diamond Yukai). Although the former film is more upbeat, and lacks much of the alienation of Coppola’s work, you do still see the darker, lonelier edges of Tokyo on the fringes.

From passionless love hotels to getting lost in the masses of humanity, and the crippling societal expectations of Japan, it’s still present. Because while Lost in Translation is always about the western perspective incubated in Tokyo’s fast-paced modernity, it seems like Kuzui’s international marriage gives her a more perceptive and localized understanding of Japan.

I’ve long been a fan of John Carney and there’s some of that energy here where music is so integral in constructing the story. No matter how humble the means, the production of the music functions as a platform and a showcase for the performers in such an authentic way. By the end, we appreciate the music and by extension the characters as well. But they both work in tandem to supersede the plot.

Some of the songs feel like absolute knockouts like “Hiro’s Song,” which can stand on its own two feet. They leave the film on a feel-good high that extends beyond the credits. With the latest reissue of the film for its 25th anniversary in 2023, it seems ripe for rediscovery by a new audience.

3.5/5 Stars