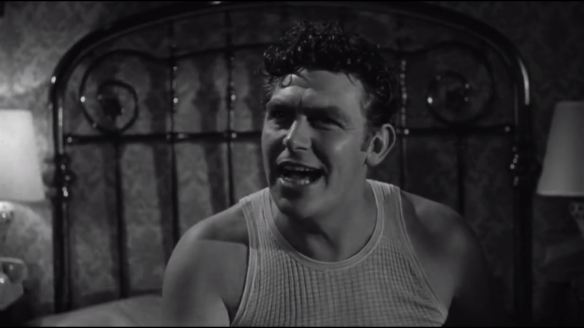

It begins unobtrusively enough. In a backwater Arkansas jail, a drunkard plays his guitar on a radio segment of “A Face in the Crowd” being broadcast from his cell. They don’t know it quite yet but soon the host who found him, Marcia Jeffries (Patricia Neal), and Larry “Lonesome” Rhodes (Andy Griffith) capture the public’s imagination. Far from just plucking Rhodes out of obscurity, Jefferies also rebrands him with an off the cuff remark and uses her daddy’s radio reach to broadcast him all around.

With such a platform, Rhodes does the rest with his wild whoops of down-home charm and strangely beguiling magnetism. He’s a natural performer and showman who knows how to form a connection with the folks at home. Soon they have created a following or as is popular in the lexicon these days a “tribe” giving him real media presence in the cultural conversation.

Someone asks him the question, “How does it feel to be able to say anything that comes into your head and be able to sway people?” But it’s true. He’s at the forefront of a grassroots democracy turning into a television phenomenon.

Meanwhile, Jefferies watches it all unfolding with bright-eyed awe and deep enthusiasm. It’s absolutely rich seeing it sweep over the country. One of the cogs in the machine is a jaded writer named Mel (an early Walter Matthau) who watches the unfoldings with grim amusement. Meanwhile, Lonesome’s ever-ambitious and cutthroat promoter (an even younger Anthony Franciosa) positions his man to continue broadening his success. Everyone’s trying to get a piece of this new pie. Because what’s more American than pie?

Rhodes keeps up his side of the bargain by purveying his own brand of “authenticity.” On one show he brings on a destitute African-American woman and gives a call-to-action and the money comes pouring in, in response. Another week he crosses a mattress sponsor and subsequently raises the man’s sales all across the country simply by belittling his product.

Soon he’s brought on to promote the product of the stuffy Vitajex company and he takes their pride and joy, disregarding their focus groups and tradition, selling the pill straight to the public. By the time he’s done with them, the public’s buying them up by the barrelful.

He also captures the imaginations and the fancy of all the young girls all across the nation — soon has them all swooning over him — but one lucky girl wins out (Lee Remick) with her baton twirling during the Ms. Arkansas Majorrette competition of 1957. Of course, Lonesome Rhodes is made the judge and after getting mobbed by the girls, he takes a shine to Betty Lou.

Marcia gets pushed further and further into the periphery of his life as Rhodes weds the frisky twirler and sets his sights on the next domain to be conquered. Politics have entered a new stage — the television age — and no man is more beloved than Lonesome Rhodes. “You gotta be a saint for the power the box can give you,” as Mel notes, and in the wrong hands, this immense power is dangerous.

Rhodes throws his support behind a stodgy old lawmaker giving him advice in the process. The film was already predicting the famed televised debate between Nixon and Kennedy. Where campaigning is about punchlines and glamor; it becomes a popularity contest and an advertising endeavor as much as a smear campaign. He uses his Cracker Barrel Show to promote the senator in a more relaxed atmosphere and has the position of Secretary of National Morale waved in front of him.

He even notes his candidate should get a dog, observing that it didn’t do Roosevelt any harm or Dick Nixon neither (referring to the well-received “Checkers” speech in 1952). Because these events begin to hint out how corruption, even double talk, begin to make the general public question “authenticity.”

In one off-handed remark, Lonesome crows, “This whole country is just like my flock of sheep.” However, like Arthur Godfrey, his downfall (though more rapid) occurs after an onscreen incident that removes his mask and undermines his image before the people. They can never see him the same way. The saboteur, as it were, is Marcia for she cannot bear to see the people taken in.

So the final trajectory is obvious — the ascension and the dethronement — but that can hardly neutralize what we have already witnessed. A Face in the Crowd lingers with fair warning, relevant to any analogous situation in the modern landscape, only magnified to the nth degree.

Earl Hagen’s down-home waterhole tunes fit The Andy Griffith Show just as this arrangement from Tom Glazer gels with A Face in the Crowd. Speaking of, I must insert a thought on what I know more about, as I grew up watching countless hours of The Andy Griffith Show.

The character of Andy Taylor obscures the fact of what a fine actor Andy Griffith was. To some extent, the same can be said of No Time for Sergeants because like the early seasons of his show, he’s just playing a bubble-headed hick. Later on, he became more of a straight man and after Barney Fife left, he settled into a more irascible role so there was an evolution.

Regardless, Lonesome Rhodes turns the overarching stereotypes of the man on their head. You can still see him as the benevolent Sheriff of Mayberry but this certainly lingers in the back of your mind. Take away the moral integrity and others-centric mentality of Andy and you wind up with Lonesome.

Given its themes about media and television, which seem like a cutting-edge indictment in their contemporary age, it seems logical to lump A Face in The Crowd with Network. Similarly, though technology and advertising continue to become more advanced and invasive, the themes explored feel, not less relevant, but more so.

We simply have to magnify them. Instead of television, we have Twitter and smartphones. Instead of people who willfully hide their intent, we have people in power who seem to blatantly disregard moral uprightness.

I want Lonesome Rhodes to be outdated and immaterial but to make such a claim would be an immense act of folly. It would cater to the same sense of ignorance and sway in all sectors of society, which led to the rise of such a person in the first place. Then and now…

4.5/5 Stars

Note: An earlier version of this review erroneously said Rip Torn instead of Anthony Franciosa (He was featured in an uncredited role).

Whatever our criticisms of the previous generations, there’s still something within me that sees something uniquely compelling about films of old. Hollywood in the 30s and 40s could sugar coat, they could oversell the drama, but there was also a general decency that pervaded many of those films.

Whatever our criticisms of the previous generations, there’s still something within me that sees something uniquely compelling about films of old. Hollywood in the 30s and 40s could sugar coat, they could oversell the drama, but there was also a general decency that pervaded many of those films. Why do you watch me? -Magda

Why do you watch me? -Magda And despite the clandestine nature of his activities he still somehow remains innocent in the eyes of the beholder. Daily he works at the post office behind the glass and in the evening he studies languages. But he’s continually drawn to this lady across the way. He feels like he knows her. He wants any pretense to meet her and so he creates a bit of fate anytime he can.

And despite the clandestine nature of his activities he still somehow remains innocent in the eyes of the beholder. Daily he works at the post office behind the glass and in the evening he studies languages. But he’s continually drawn to this lady across the way. He feels like he knows her. He wants any pretense to meet her and so he creates a bit of fate anytime he can. However, often times sex and love become synonymous terms and that is the underlying tension between Tomek and Maria Magdelena’s relationship. Though innocent, he wants true love, a love that transcends a simple physical act and is summed up with affection, intimacy, and an inherent closeness. He is taken with her beauty certainly but even more so he is invariably alone. Meanwhile, she is so enraptured with sex and denigrating such a grand (and admittedly messy) thing as love, to a simple physical act. She can’t understand this wide-eyed boy and his delusions. She’s ready to open him up to the way the world actually turns. And her callousness ultimately crushes Tomek’s tender heart. She broke it not by simply rejecting him, because this is a ludicrous love story, but truly obliterating any of the naive aspirations he had for love.

However, often times sex and love become synonymous terms and that is the underlying tension between Tomek and Maria Magdelena’s relationship. Though innocent, he wants true love, a love that transcends a simple physical act and is summed up with affection, intimacy, and an inherent closeness. He is taken with her beauty certainly but even more so he is invariably alone. Meanwhile, she is so enraptured with sex and denigrating such a grand (and admittedly messy) thing as love, to a simple physical act. She can’t understand this wide-eyed boy and his delusions. She’s ready to open him up to the way the world actually turns. And her callousness ultimately crushes Tomek’s tender heart. She broke it not by simply rejecting him, because this is a ludicrous love story, but truly obliterating any of the naive aspirations he had for love. Inspired directors oftentimes do not make themselves known in grandiose flourishes but in the smallest of touches, and in his debut, Polish newcomer Roman Polanski does something interesting with the opening of Knife in the Water. Perhaps it’s not that unusual, but it’s also hard to remember the last film where the camera was on the outside of a driving car, looking in. We see shadows of faces overlaid with credits and then finally the faces are revealed only to be shrouded by the reflections of overhanging trees glancing off the windshield.

Inspired directors oftentimes do not make themselves known in grandiose flourishes but in the smallest of touches, and in his debut, Polish newcomer Roman Polanski does something interesting with the opening of Knife in the Water. Perhaps it’s not that unusual, but it’s also hard to remember the last film where the camera was on the outside of a driving car, looking in. We see shadows of faces overlaid with credits and then finally the faces are revealed only to be shrouded by the reflections of overhanging trees glancing off the windshield. Thus, it becomes an exercise of technical skill, much like Hitchcock in Lifeboat or any other film that limits itself to a single plane of existence. Polanski’s framing of his shots with one figure right on the edge of the frame and others arranged behind is invariably interesting. Because although space is limited, it challenges him to think outside the box, and he gives us some beautiful overhead images as well which make for a generally dynamic composition. That is overlaid by a jazzy score of accompaniment courtesy of Krzysztof Komeda, a future collaborator on many of Polanski’s subsequent works during the ’60s.

Thus, it becomes an exercise of technical skill, much like Hitchcock in Lifeboat or any other film that limits itself to a single plane of existence. Polanski’s framing of his shots with one figure right on the edge of the frame and others arranged behind is invariably interesting. Because although space is limited, it challenges him to think outside the box, and he gives us some beautiful overhead images as well which make for a generally dynamic composition. That is overlaid by a jazzy score of accompaniment courtesy of Krzysztof Komeda, a future collaborator on many of Polanski’s subsequent works during the ’60s. However, at this point, as a young director, he is simply sharpening his teeth and getting acclimated to the genre a little bit. Knife in the Water builds around the three sides of a love triangle, creating a dynamic of sexual tension because that’s what tight quarters and jealousy do to people. This is less of a spoiler and more of a general observation, but the film does not have a major dramatic twist. Instead, there are heightened tensions, a bit of underwater deception, and finally a fork in the road.

However, at this point, as a young director, he is simply sharpening his teeth and getting acclimated to the genre a little bit. Knife in the Water builds around the three sides of a love triangle, creating a dynamic of sexual tension because that’s what tight quarters and jealousy do to people. This is less of a spoiler and more of a general observation, but the film does not have a major dramatic twist. Instead, there are heightened tensions, a bit of underwater deception, and finally a fork in the road. We’re used to getting our hands dirty in the thick of World War II, whether it is in the European theater or the Pacific, but very rarely do we consider the consequences that come in the wake of such an earth-shattering event. Things do not end just like that. There must be periods of rebuilding and rehabilitation. There is unrest and upheaval as the world continues to groan in response.

We’re used to getting our hands dirty in the thick of World War II, whether it is in the European theater or the Pacific, but very rarely do we consider the consequences that come in the wake of such an earth-shattering event. Things do not end just like that. There must be periods of rebuilding and rehabilitation. There is unrest and upheaval as the world continues to groan in response. There are love scenes that are quiet, subdued, and truly intimate. In fact, it feels rather like Hiroshima Mon Amour where the camera lingers so closely on two figures in such close proximity. There does not have to be great movement or dramatic interludes because having two people next to each other should be enough. The historical context in itself seems to be enough. For that film, it meant Japan post-1945. For this one, it’s Poland after the clouds of war have lifted.

There are love scenes that are quiet, subdued, and truly intimate. In fact, it feels rather like Hiroshima Mon Amour where the camera lingers so closely on two figures in such close proximity. There does not have to be great movement or dramatic interludes because having two people next to each other should be enough. The historical context in itself seems to be enough. For that film, it meant Japan post-1945. For this one, it’s Poland after the clouds of war have lifted.