With the passing of Claudia Cardinale in 2025, I took it upon myself to watch some of her movies that I had not seen before. Below, I included capsule reviews of two of her earlier performances:

With the passing of Claudia Cardinale in 2025, I took it upon myself to watch some of her movies that I had not seen before. Below, I included capsule reviews of two of her earlier performances:

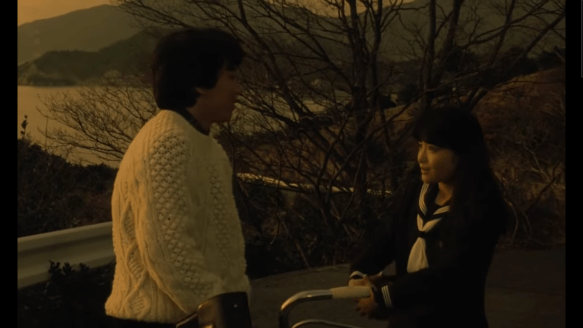

The Facts of Life (1959)

At first, I wasn’t sure what to expect from the picture. I thought it might be a comedia italiana or maybe a crime picture, but one in the vein of Big Deal on Madonna Street (Claudia Cardinale turned up in that one as well). However, the Facts of Murder feels like a more traditional police procedural, mystery story, albeit told in the Italian milieu.

Two events become crucial to the plot. First, a burglary in broad daylight where the culprit manages to flee the crowded scene without being apprehended. The police are called to investigate

In the midst of their investigation, a body is found, a person now dead next door. As the detective notes, lightning doesn’t strike twice in the same place, and yet in this case it has. There’s something rather intriguing about the lead investigator being played by director Pietro Germi (Divorced Italian Style, Seduced and Abandoned).

It took me some time to catch on, but even though it’s not a flashy part, the role does hold the picture together because he must drive the story forward, interacting with all sorts of folks and beginning to decipher what actually occurred.

There are a number of possible suspects, including a doctor cousin (Franco Fabrizi) who, at the very least, is a selfish opportunist. Then there is the spouse of the deceased, who is understandably shaken up and initially sympathetic, though he has the most to gain. There’s also something he’s keeping hidden from the authorities.

Eventually, the police round up the hands that had a part in the theft, but they still have to solve the second part that has eluded them thus far. A film such as this can so often be dominated by the men, and yet there are three performances from the actresses worthy of note

Claudia Cardinale has a fairly small but crucial role as a faithful maid to Eleonora Rossi Drago’s character. And Cristina Gajoni shows up at the end of the picture in a notable part that holds a lot of sway over the story. However, it is the indelible image of Cardinale sprinting down the dirt road after the receding car with tears in her eyes that stays with me.

If her career weren’t so ripe with many memorable films, it could just have easily been a moment she was remembered for. As is, The Facts of Murder was just the beginning of an illustrious career.

4/5 Stars

Bell’Antonio (1960)

My first inclination is that Marcello Mastroianni is technically too old for a role such as this (he purportedly joined mere days before the production started as a favor to the director). Yet, there’s also really no one else to play this role, as it stands as a romantic ideal. Antonio, the title character, is almost a mythic figure in his local community. He comes back to his parents’ home from Rome.

His reputation precedes him with stories of women throwing themselves at him and wives of government ministers left smitten. Whether it’s blown out of proportion or not, we certainly see some evidence of his romantic sway. It’s almost like everyone else wants to prove for themselves if the stories are true, and so they build and play up the mystique. You would think Antonio is the one cultivating his image, but it feels like he wants to be rid of it.

There are these social layers to the movie, also. We witness men in power, and they have a desire for women who know how to trade in their feminine wiles. The film is transposed from a novel set in fascist Italy, and these scenes bear this out the most obviously (it felt reminiscent of scenes in a later picture like The Cremator).

There is the brokering of social transactions even between families like crusty barons or haughty royalty of generations gone by. Initially, Antonio is vehemently opposed to the union, only to receive a picture of the woman his parents have orchestrated for him to marry. He can’t stop looking at it. She’s remarkable!

In her own way, an aura is built around Barbara as well, just like with Antonio. Thankfully, for the sake of the movie, she is portrayed by none other than Claudia Cardinale. They are eventually wed as the social script suggests. However, status and social economy are, again, predicated on virility or at least the projection of it.

The society seems to idolize womanizers even as much as they condone a narrative of men sowing their wild oats. This includes Antonio’s father. And sadly, we see the hypocrisy of the church within these same power structures invested in the letter of the law and not the heart or posture behind it.

The punchline of the movie is the fact that the church will annul the marriage because they haven’t consummated it and gotten pregnant within 12 months. It’s a catastrophe on all fronts! Compared to how they treat infidelity and affairs, it makes one queasy.

3.5/5 Stars