In the imperialist traditions of the likes of Tarzan The Ape Man (1932), Gunga Din (1939) and even Lawrence of Arabia (1962) comes The Lives of Bengal Lancers. We cannot take the era or the colonial sentiments for granted like the contemporary viewer did since we must reconcile with the complicated filter hindsight lends.

It’s a bit like an old Cowboy and Indians picture except instead we have lancers and Indians. In theory, our allegiances lie solely with the dominant sides, and the rebels have our ire because revisionist filmmaking had yet to be created. This is the victor’s myth.

Director Henry Hathaway in later years would be remembered as a veteran of both crime pictures and classic John Wayne westerns including True Grit. The Lives of Bengal Lancers was his first formidable success, and the action and adventure itself are frankly quite thrilling.

Gary Cooper, as one of American’s dashing action heroes of the day, plays our protagonist MacGregor, a rough-edged soldier who nevertheless conceals the age-old heart of gold. A prime example comes when he makes up some excuse to send a new recruit to call on his father so they can talk in confidence. The boy has yet to see his flesh and blood face-to-face without constant rules and regulations getting between them.

Actually, we have two new recruits who come aboard: Forsythe (Franchot Tone) a glib sportsman who finds great relish in crossing wills with MacGregor and then dashing Lieutenant Stone (Richard Cromwell) still wet behind the ears. His father is the commander of the entire outpost. A journeyman soldier, “Old Ramrod” Stone (Guy Stander) is an incorrigible stickler for duty and discipline.

But the task at hand is the apprehending of a charismatic gunrunner and local outlaw Ahmad Khan (Douglass Dumbrille), who subsequently holds great power over the territory. The favored sport of “Pig Sticking” provides a handy cover for snooping around.

Most delightful of all is the one-upmanship fostered between our two manly specimens played by Cooper and Tone. The constant friendly competition between the blunt Canadian straight-arrow and the more polished and tempered “Blues Man” brought up in Britain is one of the film’s finer assets.

But of course, the inevitable happens and our heroes get captured by Khan. The famed line misstated on numerous occasions is actually, “We have ways to make men talk.” However, it feels anticlimactic considering.

It’s also difficult to decide if it’s to the film’s credit or not, but the villain, played by the white actor Douglas Dumbrille, is not trying to hide it. He is educated and resists playing up some savage image. He leaves that to all his underlings who do his every bidding.

While imprisoned, our heroes spend their idle time, outside of being tortured, playing at cockroach races and letting their stubble grow out. Once again, it represents the very best of the film instilled by the performances of Cooper and Tone opposite one other. Because everyone else we can easily see in any of these old adventure epics. It feels like standard stuff. They are not.

Certainly, the story teases out this issue between the duties of a soldier and the scruples of a man with inbred common decency. Should the family be sacrificed for the sake of the outfit? Is a man who has poured everything into his military career because he believes in regulation fit to be praised and venerated? The commander’s appreciative colleague (C. Aubrey Smith) lauds his actions acknowledging, “Love or death won’t get in the way of his duty.” Whether that is an entirely good thing remains to be seen.

Of course, we see analogous themes in even some of John Ford’s pictures like Fort Apache and specifically Rio Grande. The latter film has the same father-son dynamic playing out, except inside of conveniently killing off the spouse to streamline the conflict, that film actually digs into the themes more definitively. Anyone who has seen the film will agree Wayne and Maureen O’Hara’s relationship is the most interesting dynamic. A close second is the camaraderie of the soldiers.

In The Lives of Bengal Lancers, again, we have no such relationship, so the film is at its best with the soldiers sharing their lives together. One must note while the western might be dead, these old adventure yarns feel even more archaic. This brings up a host of other issues to parse through.

Watching the film unfold we cannot know for sure if we are on the right side of a righteous or unjust war; the underlying problem is the film does not leave it open. It’s already accepted who the conquers and heroes will be. I have nothing against the likes of Gary Cooper and Franchot Tone. I rather like them. But I can’t help but feel their team is playing a bit unfairly. The deck is stacked in their favor.

This ties into another notable caveat to make the viewer wary because Lives of a Bengal Lancer was purportedly a favorite of Hitler. In its digressions, he saw agreeable conclusions to inspire his own empire — the Third Reich — namely an unswerving duty to country along with elements of racial superiority.

Because it is these Brits with their bravery and know-how who are able to hold off the hordes of enemies. Their valor in itself is not an issue but placed up against their enemy, it is slightly troubling. The fact Hitler made it compulsory viewing to members of the SS is another level of bone-chilling. It’s hard to look at the picture in the same light after such a revelation.

3.5/5 Stars

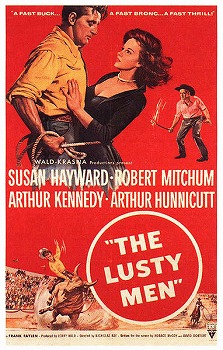

The connotation of the film’s lurid title feels slightly deceptive. Because The Lusty Men might have basic elements of men who desire after women but it’s fairly restrained in this regard. At least more than I initially conceived. However, it is a film characterized by a zeal or a lust for life. The male protagonists are intent or were formerly driven in the pursuit of high living with all the benefit such a life affords.

The connotation of the film’s lurid title feels slightly deceptive. Because The Lusty Men might have basic elements of men who desire after women but it’s fairly restrained in this regard. At least more than I initially conceived. However, it is a film characterized by a zeal or a lust for life. The male protagonists are intent or were formerly driven in the pursuit of high living with all the benefit such a life affords.

As of late, it feels like the world has entered a bit of a Mr. Rogers Reinnaissance. He’s been gone since 2003 and yet last year we had Morgan Neville’s edifying documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? There are podcasts galore including Finding Fred and then Mr. Rogers’s words, whether before the Senate Committee or pertaining to scary moments of international tragedy, seem to still provide comfort and quiet exhortation to those in need.

As of late, it feels like the world has entered a bit of a Mr. Rogers Reinnaissance. He’s been gone since 2003 and yet last year we had Morgan Neville’s edifying documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? There are podcasts galore including Finding Fred and then Mr. Rogers’s words, whether before the Senate Committee or pertaining to scary moments of international tragedy, seem to still provide comfort and quiet exhortation to those in need. I Want to Live! calls upon the words of two men of repute to make an ethos appeal to the audience. The first quotation is plucked from Albert Camus. I’m not sure what the context actually was but the excerpt reads, “What good are films if they do not make us face the realities of our time.” This is followed up by some very official-looking script signed by Edward S. Montgomery, Pulitzer Prize winner, who confirms this is a factual story based on his own journalism and the personal letters of one Barbara Graham.

I Want to Live! calls upon the words of two men of repute to make an ethos appeal to the audience. The first quotation is plucked from Albert Camus. I’m not sure what the context actually was but the excerpt reads, “What good are films if they do not make us face the realities of our time.” This is followed up by some very official-looking script signed by Edward S. Montgomery, Pulitzer Prize winner, who confirms this is a factual story based on his own journalism and the personal letters of one Barbara Graham.