There’s little doubt Blood and Sand was a follow up to The Mark of Zorro (1940) meant to capitalize on the lucrative romantic pairing of devilishly handsome heartthrob Tyrone Power and winsome ingenue Linda Darnell. But what it sets out to do, it achieves through an ability to capture us in a joyously Hollywood confection. It pulls out all the stops to establish Spain for the moviegoing audience. Flamenca, guitar, castanets, swirling skirts, and sashaying ladies are all present bursting forth from the screen with multicolored gaiety and merriment.

The picture in straightforward fashion charters the rise of a young boy into a renowned matador with aims at commanding the grandest stage in all of Seville. Juan Gallardo (Power), buoyed by a tight-knit band of friends and propelled by lifelong ambition, is ultimately able to realize his dreams and to garner all the laurels lavished on the man of the hour.

Most important of all, he’s finally able to marry the girl whom he’s loved since childhood, the virginal beauty Carmen Espinosa (Darnell). She has dutifully waited for his triumphant return when he serenades her with a full band and presents her a wedding dress to pronounce his everlasting love. They’re young and deliriously happy.

While initially maligned as a fifth-rate talent, now the famed purveyor of public opinion, Natalio Curro, christens Gallardo the finest matador in all the land. Laird Cregar is more than capable as the pompous bullfighting critic who relishes the spotlight as well as his reputation as a tastemaker.

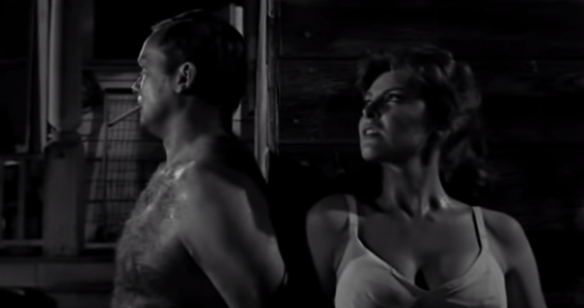

Likewise, everyone wants Juan to be the godfather of their child. He is in high demand and he catches everyone’s eye. Namely, the recently returned socialite Doña Sol des Muire (Rita Hayworth) coming from irrefutably high-class stock. She has her pick of the litter and she immediately becomes diverted by this dashing matador tossing him down a red rose in return for a couple tokens of his goodwill.

Meanwhile, Carmen remains faithful by his side praying every day he enters into the ring to do his work. She dotes on him with breakfast, reading the headlines about his finest hour, and remains his constant companion. However, the allure of the “other woman” ensnares him and his fate is all but sealed. Just as he baits the bull, she soon has him reeling much the same. But the only real person to blame is himself.

His wife is betrayed in one heart-breaking confrontation, his finances are in disarray, his temper has alienated many of his closest allies, and his success in the ring has begun to falter. None of these plot developments are unforeseen. On the contrary, we expect them. As his mother reminds him, taking cues from the Biblical parables, “One can’t build on sand.” Because everything you worked so hard to erect will just as easily come tumbling down when the downpour hits.

It’s as much his own fault is it is the fickle masses who are so unforgiving. Pretty girls like Doña just as easily move on to a new toy, this time Juan’s lifelong rival Manolo (Anthony Quinn). And of course, Curro has been quick to pronounce the new man as the latest shining comet of the new season. He fails to add that comets burn brightly only to fizzle out in a nose dive. The tragic metaphor is a little too obvious.

But again, the picture is all spectacle and it’s ultimately bolstered by lavish costumes and the early shades of Technicolor offering a seminal example of 3-strip Hollywood opulence. Rouben Mamoulian’s artistry in mise en scene from his days with the stage are on display, played out to the nth degree. The screen and the stars are easy on the eyes. The director purportedly kept cans of spray paint on hand to touch up any necessary blasé patches with enhanced color. However he achieved it, Blood and Sand generally works.

True, bullfighting always seems like a barbarous pastime even as Hollywood can’t show that much. It does feel like a modernized incarnation of gladiatorial battles. Just as the public is petty, it’s even a little difficult to feel sorry for our protagonist, though Linda Darnell, continually surrounded by Roman Catholic imagery, remains as the last vestige of saintly virtue. She’s never been so pure.

The same cannot be said for Rita Hayworth in her secondary role, which in itself is a rather strange circumstance since she had yet to reach the heights of her later career and pictures like Gilda (1946). Tyrone Power could coast on his looks and charisma alone and he pretty much does.

3.5/5 Stars

Without question, Hangover Square is in many respects analogous to The Lodger with the reteaming of director John Brahm with Laird Cregar and George Sanders. However, the biggest difference is that we have Cregar putting on on a new persona and losing over 100 pounds!

Without question, Hangover Square is in many respects analogous to The Lodger with the reteaming of director John Brahm with Laird Cregar and George Sanders. However, the biggest difference is that we have Cregar putting on on a new persona and losing over 100 pounds!

The proverbial stranger rides into town looking for a place to wash up and grab a bite to eat. We get the sense he might be sticking around. Except, soon enough, he turns right back around and buys a ticket on the first train out of town. Because he has business to attend to.

The proverbial stranger rides into town looking for a place to wash up and grab a bite to eat. We get the sense he might be sticking around. Except, soon enough, he turns right back around and buys a ticket on the first train out of town. Because he has business to attend to.

What can I say? I am one of the proud and the many who loved The Beatles before they loved any other type of music. So when I watch Help! I look for all the best in it because that’s all that I can do.

What can I say? I am one of the proud and the many who loved The Beatles before they loved any other type of music. So when I watch Help! I look for all the best in it because that’s all that I can do.