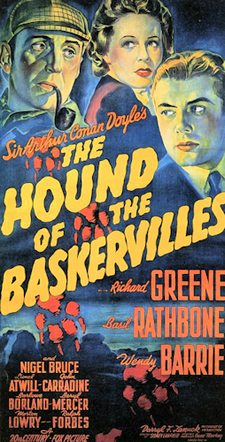

“Elementary My Dear Watson” owes its indelible stature in the lexicon hall of fame to this second installment in 20th Century Fox’s Sherlock Holmes series. The studio obviously did not gather the phrase to have that much resonance as they gave up on the franchise only to have it be picked up by Universal Pictures for many, many more outings. This would be the last one set in its original historical context and it’s unquestionably the gem of the lot.

Though the analogy breaks down, it was easy to see the first installment of Rathbone’s outing as Holmes like Peter Sellers in the original Pink Panther (1963). You get a sense of a formidable character who is subsequently given greater fluidity and is, therefore, able to break into their own. A Shot in the Dark (1964) was far better than its predecessor because it gave Inspector Clouseau his own vehicle.

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes proves to be a superior film for two such reasons. First, Rathbone and Bruce coming off their success are put front and center in this picture. But also while the first film was an adaptation of a Doyle story, this picture is an original narrative thus taking the characters from the page and extrapolating them onto the screen in new and intriguing ways.

In one sense, I’m glad for that change because whereas The Hound of the Baskervilles was much better as detailed by Doyle’s pen, this story is a creation blessed with an imagination. Taking all that is good about the original work and synthesizing it into something that never quite loses the spirit but on the contrary, builds on it all the better for distillation to the big screen.

The remarkable revelation is that the story does provide a true conundrum for Holmes as he battles it out with his arch nemesis Moriarty in a chess match of wits. While there are several moments that seem uncharacteristically on-the-nose for a man of his intellect, otherwise we relish the game and his astute observations.

It opens in a courtroom as Professor Moriarty is exonerated for a crime that everyone seems to agree that he committed. Only moments after the pronouncement Holmes rushes into the courtroom with the needed evidence. But it’s far too late. His rival has lived to scheme another day and what a scheme it is. He plans to pull off the crime of the century by distracting Holmes with two toys that he won’t be able to put down. He likens Holmes to a fickle little boy easily distracted and he plans to exploit his idle curiosity.

What unravels and what is articulated by the script is a lovely piece of intrigue that provides many distractions not only to Holmes but his audience as well. We know full-well that though they might appear completely unrelated, they’re indubitably tied together. It’s simply a matter of understanding how and for what purpose.

The first involves a young woman named Anne Bramdon (Ida Lupino). She comes to Mr. Holmes on the behalf of her older brother who has received an ominous note. The reason she’s worried is that her dear father received much the same message before he died under strange circumstances years before.

Although it ultimately takes a back seat to this more interesting case, Holmes is also counted on by his friend at the Tower of London to help with security in the transfer of a priceless diamond to be added to the Crown Jewels.

Holmes is caught up in this perplexing case in front of him as Bramdon’s frightened brother is attacked by a mysterious assailant and soon after the lady gets a note of her own telling her to attend a certain social gathering of a longtime friend. Holmes advises her to go as he will be there to protect her but of course, the date and time are the exact same as the jewel transfer. You see the point already.

Rathbone makes another stunning showing in disguise apprehending the killer and dashing off to thwart another crime as Moriarty cleverly infiltrates the Tower’s security, no thanks to Watson. George Zucco seamlessly embodies an intellectual yet sociopathic mind filled with disdain for human life. He asserts in one such scene to his harried valet that killing a plant should be a far greater offense than taking human life. He proves overwhelmingly that a superior villain with brazen intentions elevates any story.

Director Alfred L. Werker shoots the finale with some amount of artistry that heightens the climax to an agreeable apex. It goes down as it must on the top of the Tower of London and what is curious but rather refreshing is that there are no back and forth monologues of doom and heroism. Actions speak for both our hero and villain. While London fog now seems like free atmosphere and little else, the film is actually at its best in visual terms with well-lit Victorian interiors.

The finest success of this film was in projecting a certain image or reputation that extends far into the present age. Watson became an incorrigible bumbler. Holmes a cinematic detective both partially sanitized and still witty. Moriarty remains one of the standards for villains to this day. And with so many different iterations on these same characters, the influence on Robert Downey Jr. to the modernized Benedict Cumberbatch is equally evident. There are few qualms acknowledging the impact of such a sublime mystery adventure as this.

4/5 Star

Though there’s not a shred of doubt this picture was filmed on a Hollywood backlot, our story takes place in 1889 on the Moors of Dartmoor in Devonshire. It’s all very British and when you do a quick scan of the most British figures coming out of literature and pop culture, you would probably find few higher on the list than Sherlock Holmes.

Though there’s not a shred of doubt this picture was filmed on a Hollywood backlot, our story takes place in 1889 on the Moors of Dartmoor in Devonshire. It’s all very British and when you do a quick scan of the most British figures coming out of literature and pop culture, you would probably find few higher on the list than Sherlock Holmes.

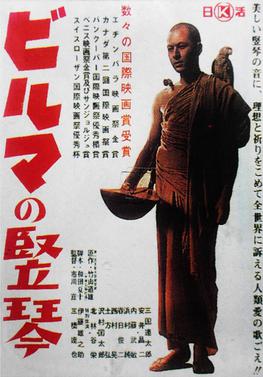

Put in juxtaposition with Kon Ichikawa’s later rumination on WWII, The Burmese Harp is a romanticized even simplistic account of the Japanese perspective of the war. However, this is not to discount the mesmerizing nature of the story that is woven nor the overarching truth that seems to linger over its frames.

Put in juxtaposition with Kon Ichikawa’s later rumination on WWII, The Burmese Harp is a romanticized even simplistic account of the Japanese perspective of the war. However, this is not to discount the mesmerizing nature of the story that is woven nor the overarching truth that seems to linger over its frames.

Hirokazu Kore-eda has quickly become one of my favorite Japanese directors, and I consider it fortuitous that this affinity has cropped up in such a fertile period. Shoplifters is a high watermark in his already illustrious career.

Hirokazu Kore-eda has quickly become one of my favorite Japanese directors, and I consider it fortuitous that this affinity has cropped up in such a fertile period. Shoplifters is a high watermark in his already illustrious career.