Puzzle of a Downfall Child (1970)

Jerry Schatzberg took his career as a fashion photographer and integrated it into a splintering portrait of a model based partially on his experiences with real-life inspiration Anne St. Marie. Like Blow-Up it is a film about the image, but in this case the visuals often play against disembodied voices obscured from view. The camera also seems to have a general infatuation with lips and speaking voices.

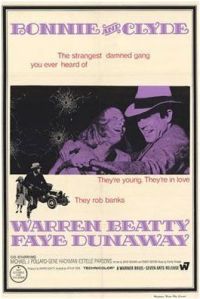

Out of these inspirations, the film becomes a stellar showcase for Faye Dunaway at the height of her powers, giving a scintillating performance — striking and yet perilously fragile. Her very diction fascinates, how it’s stunted — rising and falling — in a very particular cadence, attempting to modulate. It’s just precisely false enough to suggest instability and the film is built on this theme. She is the cypher — the puzzle to be put back together.

As she confides in friends, the picture charts this fractious course of Lou’s career, personal relationships, and insecurities. She slaloms through her memories, past and present, stitching together her life into a disordered patchwork. It becomes a perplexing ever more morose portrait of a woman in need of comfort and support in her vulnerable mental state. But the film really functions best as form over content.

The intrigue comes not in any manner of narrative cohesion but precisely because of the dissolution, a woman becoming more and more fragmented with time. It’s not an altogether original concept. Many great actresses have tried their hand with much success. Still, Carole Eastman’s spin on the dimensions of a gorgeous woman with faltering psychology feels like a nexus in the tradition. It’s also an unjustifiably underseen showing by one of the ’70s biggest attractions. Faye Dunaway admirers take note.

3.5/5 Stars

Panic in Needle Park (1971)

“Needle Park” is a nod to the shorthand of heroin addicts and it totally throws itself in their world and subsequently became one of the most harrowing depictions of drug use in the ’70s. The screenplay was written by none other than Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne from a novel by James Mills.

We get the opportunity to watch an up-and-coming stage actor, Al Pacino, submerging himself in a role and showcasing a depth that would become the bedrock of all his successes throughout the 1970s. He would join a group of actors, the De Niros, Nicholsons, and Hoffmans, who would help come to define the New Hollywood as it was being formed on the spot.

From the outset, it’s easy to be a bit wary of his mannerisms, the lip-smacking, and the sense of bravado. Then, he proceeds to go for the jugular. It’s an ugly, tawdry sort of world dictated by sex, drugs, and theft. This is how people subsist if you can call it a living at all. Where everyone’s brother is a two-bit crook and everyone else has done a stretch of time.

It’s a film that has very much a Midnight Cowboy milieu. We have the walk and talks down the streets of New York, but like Schatzberg’s next film, Scarecrow, it’s also fundamentally a film founded on a relationship of two.

If they have so many demons, the one thing they have is their tight-knit community. However, they are personally crippled by relational turbulence, always desperate to find their latest fix. It drives their desires and turns them into momentary ghosts of human beings, self-serving and a shell of their best selves.

Kitty Winn is naturally beautiful like audiences grew accustomed to seeing in the ’70s with actresses like Ali McGraw and Katherine Ross. However, her particular meekness plays well with the raw ferocity of Al Pacino, and they remain the nucleus of the drama. It doesn’t have to be about much. It simply needs to keep them at its core.

Pacino would get The Godfather next partially on the shoulders of this performance and it’s almost inconceivable to think of Michael Corleone without those deep, searching eyes of his. It’s so easy to look in their eyes — Winn’s too — and see an inkling of who they are. You can condemn their self-destructive tendencies and then turn right around and pity them.

3.5/5 Stars

Scarecrow (1973)

With Schatzberg, the salient features connecting his movies isn’t overtly apparent, but it does feel like the material really guides the output. So much relies upon and flows out of the sense of performance whether Dunaway, Pacino, or Hackman and Pacino here in Scarecrow. But first, can we take a moment to acknowledge what a stroke of luck it is: Pacino and Hackman in a movie together, a movie predicated on character, and they could not be two more disparate personalities.

Because this was on the other side of The French Connection and The Godfather, two of the biggest hits of the ’70s so far, and yet our two stars find it within themselves to do a picture like this. It’s not big budget, with a lot of thrills or prestige, but they more than make it something worth watching regardless of scale.

It feels a bit like Waiting for Godot with tumbleweeds rolling by as photographed by Vilmos Zsigod . Finally, they trade words and make their way to a diner. Their odd brand of friendship is born.

Like any good drifter you might find in the work of John Steinbeck, Max’s idea of a slice of paradise is getting his own car wash. In truth, if the Monterey laureate had been alive and kicking in the ’70s, Scarecrow is exactly the kind of story he might write because it almost feels suspended in time. They have a friendship and camaraderie that feels deeply indebted to George and Lennie. It is almost difficult to unsee it once you’ve drawn the parallels.

Pacino’s philosophy in life is a lot more amenable if a bit eccentric. To borrow the film’s main analogy, he believes scarecrows are not frightening. They actually look so ridiculous that they got the crows laughing and they fly away. So while Max is bellicose, constantly taking umbrage with others, running off his mouth, and getting in brawls, Lion’s always there to provide some equilibrium. As performers and actors, they feel totally at odds and yet we’re ceaselessly fascinated to have them together as a creative battery.

There’s a scene where Hackman tries to chat up the bodacious Frenchy. She’s brought them beers as they move items in the junk heap. But all throughout the scene, Pacino is clunking around making a racket and getting in his way. In another moment of lunacy, he’s sprinting through a department store as a diversion that winds up leaving his accomplice flabbergasted. Max’s so hoodwinked by it all, he sets back down the purse he planned to nick.

Because Lion’s a bit of a jester, simpler in spirit, yet fiercely loyal. Even when they have a spat, he’s hesitant to leave his friend. Hackman’s performance is founded on his irascible nature. He’s loud and obnoxious, begrudging, and yet his slivers of goodness begin to show. He becomes a friend and protector to his buddy. It’s heartbreaking when he finally reveals his tender-hearted feelings. That car wash and Pittsburgh seem so far away. But then again, it was hardly a real place to begin with.

3.5/5 Stars

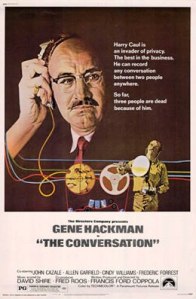

In the 1970s political paranoia involved issues in the realm of Watergate. Government conspiracy and that type of thing perfectly embodied by some of Alan Pakula’s best films. But it’s important to realize in order to better understand this particular thriller, the 1980s were a decade fraught with fears of Soviet infiltration compromising our national security. The Cold War was still a part of the public consciousness even after being a part of life for such a long time already. So No Way Out has a bit of Pakula’s apprehension in government and maybe even a bit of the showmanship of Psycho with some truly jarring twists.

In the 1970s political paranoia involved issues in the realm of Watergate. Government conspiracy and that type of thing perfectly embodied by some of Alan Pakula’s best films. But it’s important to realize in order to better understand this particular thriller, the 1980s were a decade fraught with fears of Soviet infiltration compromising our national security. The Cold War was still a part of the public consciousness even after being a part of life for such a long time already. So No Way Out has a bit of Pakula’s apprehension in government and maybe even a bit of the showmanship of Psycho with some truly jarring twists. The last time I saw Hoosiers it was on VHS and I was only a boy and I hardly remember anything. Gene Hackman yelling. Dennis Hopper as a drunk. Jimmy the boy wonder, “The Picket Fence”, and of course Indiana basketball at its finest. But in those opening moments, as he drives into town and walks through the halls of his new home, I realized just how much I miss Gene Hackman. Yes, he’s still with us but the moment he decided to step out of the limelight and retire from his illustrious career as an actor, films got a little less exciting. His passionate often fiery charisma is dearly missed.

The last time I saw Hoosiers it was on VHS and I was only a boy and I hardly remember anything. Gene Hackman yelling. Dennis Hopper as a drunk. Jimmy the boy wonder, “The Picket Fence”, and of course Indiana basketball at its finest. But in those opening moments, as he drives into town and walks through the halls of his new home, I realized just how much I miss Gene Hackman. Yes, he’s still with us but the moment he decided to step out of the limelight and retire from his illustrious career as an actor, films got a little less exciting. His passionate often fiery charisma is dearly missed.