Sometimes you start a film and there’s such a specific sense of place, rhythm, and tone you perk up in anticipation. I felt that sensation from the opening credits of this new film starring Daisy Ridley.

Sometimes you start a film and there’s such a specific sense of place, rhythm, and tone you perk up in anticipation. I felt that sensation from the opening credits of this new film starring Daisy Ridley.

The score is replete with a few murmuring voices and a harp, and there’s the muted color palette of a certain sleepy town in the Pacific Northwest. There’s an instant sense of where we are and what end we might be converging on. That is, besides death.

Sometimes I Think About Dying is directed by Rachel Lambert from a screenplay co-written by Kevin Armento, Stefanie Abel Horowitz, and Katy Wright-Mead. It’s easy to pigeon-hole it as a project filling the quirky indie fix and the proof of concept seems littered with a minefield of tropes.

Fran (Ridley) works in an office — the dreaded 9 to 5 desk job — and between emails and spreadsheets her mind will drift away to far off places in her subconscious. It’s also a movie with plenty of inserts of contorted posture. At times it’s uncomfortable watching her exist.

Robert (Dave Merheje) is the new guy. He’s personable and a little dorky in a charming sort of way. Make him a cinephile and you have a perfect movie character. He feels like the Yin to Fran’s Yang and somehow that bodes well.

They don’t so much have chemistry as stunted, awkward interactions. They go see a movie at the local art house theater. They have pie afterward as one does. One wouldn’t label them a couple so much as they’re two people looking for a connection; he’s just moved to town and well, she’s not the most sociable human being.

In this depicted life of dreary and at times surreal isolation, human connection is such a moving balm. They meet up again and she sees his new home, gets the tour, and learns he has his own past; he’s been divorced, not once but twice.

Ridley’s performance does feel like a performance, but the act of playing something so stunted and repressed and yet giving the sense of a charming person just trying to get out is such a meaningful focal point. Because in another movie it would vie to get bigger, but she never allows it to get into a cartoonish heightened reality of indie purgatory.

A distinction must be made. Fran doesn’t hate her life. She’s good at her job and in her own way is a part of the ecosystem in the office. Whereas Excel sheets and requisition forms are soul-crushing for someone like me, Fran seems to thrive in such a regulated environment. But that doesn’t mean she doesn’t also feel the pangs of loneliness. It’s not like they are mutually exclusive; people are nuanced.

Within the context of the film, budding feelings are meager but precious. Her personal hurt and even her greatest transgression are never extended blow outs but these contained moments thoughtfully developed within time and space by the filmmakers.

Fran and Robert get invited to a get together and they both oblige. The subsequent gathering of murder in the dark is a nice evocation on the movie’s primary theme. It’s a visualization of death for a character who does consider its headiness from time to time. The best parts of these scenes is that they feel like a rambunctious good time. That is one of the movie’s strengths: balancing these emotions of warmth and affability with real melancholy.

Robert tells her later in the car, “You’re secretly good at a lot of things. You just don’t let anyone know.” It’s true. Introverted people like this do exist in the world. I feel like I know at least a few of them. On the surface, they seem so taciturn and unassuming but there interior lives or even what they do in their off hours are so vibrant. They offer so much, but they don’t need to tell everyone about it. Selfishly I wish we knew about more of them because we would do well to learn from their example.

My primary critique of the movie initially might have been its opening runway. It felt like for a fairly truncated film, it took a lot of time to get to Robert’s introduction; we even watch as they give a going away party to his predecessor who is set to retire and go on a cruise with her husband.

But even this is paid off when Fran stops by a local coffee shop to get donuts for the office. She’s going through a different kind of pain and regret because she said something regrettable that she cannot take back; she wants to acknowledge her remorse; tell Robert how she feels. But how can she do that if she can barely string two sentences together?

There Fran bumps into her retired co-worker surprised. She was supposed to be on a cruise. Except her husband had a stroke; she couldn’t bear to tell anyone and so now she drinks her coffee alone and looks out the window at the harbor wistfully. Fran could have traded pleasantries and left it at that. There is no personal utility to stick around, and yet she stops and sits down. She makes the decision to listen and her reactions feel real.

Somehow these feelings make her empathy and concern genuine. The action of getting something for her coworkers — a learned altruistic behavior is one thing — but there is also another turn. For one of the first times, we see her sympathy on display for another human being. She connects even if it’s just a little thing.

Later, she asks Robert genuinely, “Do you wish you could unknow me?” What a question, but it comes from such a place of honesty and fear. It fits hand in hand with the hypothetical question, “If you died tomorrow, would anyone care?” Could the lie be true? The voices in our own heads can be vicious.

There’s probably an HR caveat in here somewhere, but a movie is a movie. What lingers is this reverberating optimism. Human connections are worth the risk and effort. I left the film thinking, “Me too, Fran. Me too.” I resonate with this title though not because of some kind of ideation. From dust we come and from dust we will return.

In the final embrace of the movie, it’s in a copy room. But within seconds it’s transformed into a garden-like greenhouse — a little slice of paradise. The imagery seems only fitting. We were not made to be alone.

3.5/5 Stars

Kudos must be extended to Richard Linklater for actually being proactive and going out to shoot the movie countless of us have doubtlessly tossed around in our mind’s eye. Taking our town — the places we know intimately — and building a portmanteau out of it with a group of friends.

Kudos must be extended to Richard Linklater for actually being proactive and going out to shoot the movie countless of us have doubtlessly tossed around in our mind’s eye. Taking our town — the places we know intimately — and building a portmanteau out of it with a group of friends.

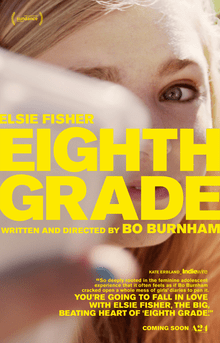

It’s not exactly The Godfather but in its opening monologue, using the awkward tween, like-laden mouthpiece of Kayla, Bo Burnham re-exerts his creative voice on the media landscape. What is more, in a world becoming continually more obsessed with relevance, shareability, and trends, Eighth Grade promises something of actual substance.

It’s not exactly The Godfather but in its opening monologue, using the awkward tween, like-laden mouthpiece of Kayla, Bo Burnham re-exerts his creative voice on the media landscape. What is more, in a world becoming continually more obsessed with relevance, shareability, and trends, Eighth Grade promises something of actual substance.