“No Ma. They ain’t my people. To tell the truth, I don’t know who’s my people. Maybe I don’t got any.” – Elvis as Pacer Burton

“No Ma. They ain’t my people. To tell the truth, I don’t know who’s my people. Maybe I don’t got any.” – Elvis as Pacer Burton

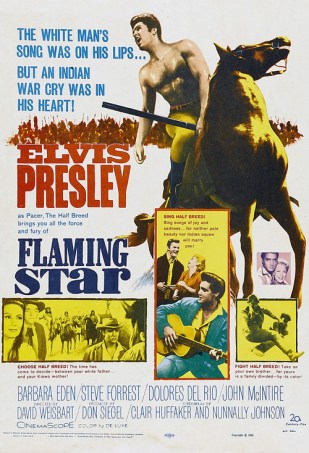

If I may be so bold The Flaming Star feels like an inflection point in Elvis Presley’s film career. It comes at a time where he’s still given the opportunity to act, and if he’s not some great talent, he’s certainly a charismatic performer in things like King Creole and Clair Huffaker’s Flaming Star.

G.I. Blues came out the same year as Flaming Star, and it feels like a schematic for the rest of his films under Hal B. Wallis. They punched up the songs and mostly stripped down the plots. All they needed was Elvis as a commodity, not an actor, because that’s what tween audiences were paying for. Money talks.

Although you can hardly equate the two, The Flaming Star compares favorably to something like Rio Bravo in how a musical interlude is used only once within the broader narrative. Granted, this film is much more plot-driven than Hawks’s hangout movie.

I would not initially peg director Don Siegel for this kind of picture — it feels uncharacteristic — and yet you can see what he can bring to the movie, which at times has a ferocity and flashes of violence. Also, it’s about as far afield from a typical Elvis picture as you can get, being both an oater and a drama seething with family drama rather than cotton candy pap.

While initially the Native Americans make for a handy purveyor of conflict, there is another element that proves slightly more intriguing. Elvis’s parents are played by John McIntire and Dolores Del Rio so he’s part of a multi-ethnic family in a time where that is frowned upon as being scandalous. People like this are to be ostracized since they deviated from the status quo of cultural norms.

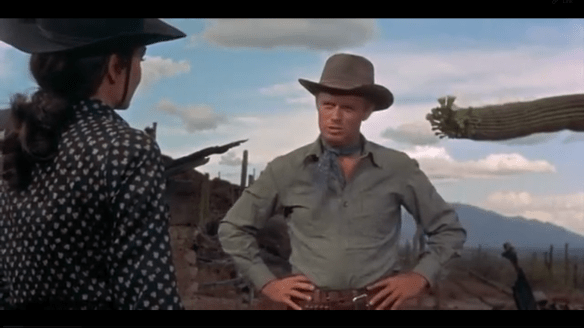

Because of its confluence of themes, it brought to mind two pictures in particular. Although Gunman’s Walk is more of a Cain and Abel story on the range, The Flaming Star provides a variation on these themes. Pacer (Elvis) and Clint (Steve Forrest) are far more benevolent, and yet in the broader society, there’s no denying that they are perceived differently.

Likewise, Bhowani Junction casts another famed dark-haired star, Ava Gardner, as a sympathetic mixed-race character. The story bristles with flaws out of the era, and yet its context allows it to court themes about personal identity and racism at a time when many of these themes were either sordid or commonly disregarded without much consideration.

Even the Native Americans are given some motivation, and they slowly grow into the movie as represented by Buffalo Horn (Rodolfo Acosta), a warrior who knows the Burtons even as he tries to protect his people’s way of life.

From his perspective, they must fight or else die with the influx of settlers; there’s also an especially aberrant strain of racism going through the white community. Given this context, it’s hard not to appreciate why the Indians have resorted to violence. Because there is very little middle ground. They see their way of life dwindling and slowly being made extinct.

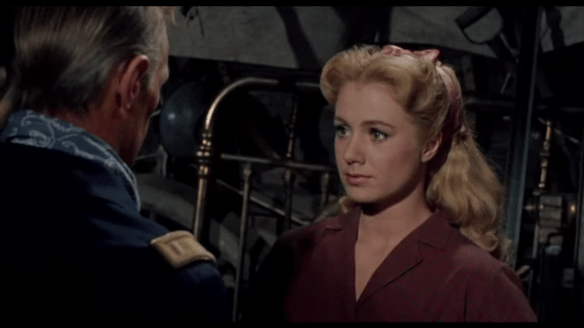

In fact, the Burtons represent that middle, and they are on especially tenuous ground, caught between two warring sides as they look to maintain and defend their homestead. I imagined Barbara Eden would be a frothy love interest on the beach. Instead we get a young woman burning with anger. Her town grows wary and more prejudiced against the Burton family since they are left mostly unharmed while many loved ones in the white community have been killed.

Some of the beats of the movie feel inevitable, and it’s a credit to the performers that they are able to imbue them with meaning. I think of John McIntire when he eulogizes his wife. The story calls for her to be sacrificed, and yet he loved her dearly. He makes the loss stick so it means something consequential.

As they stand near her grave, he recites the words from Genesis: “And Adam called his wife Eve because she was the mother of all living.” Then, he looks up to God and asks him to take care of his wife. He means it sincerely.

Later, as their livelihood continues to crumble and fracture, Mr. Burton gives his blessing to Pacer, knowing what he feels led to do, turning away from the white community that now rejects him.

Although McIntire isn’t lauded or always well-remembered beyond the classic movie community, his performance here shows the breadth of his work. He could be a tough old cuss, and yet there’s such a moving humanity to him here.

He’s far from perfect, but we sympathize with him and the life he chose. He didn’t decide who he fell in love with; he wasn’t trying to make any kind of statement. He simply fell in love with a woman who didn’t look like him, got married, and raised two sons. Now in spite of his best efforts, his boys are forced to live with the consequences.

The flaming star itself is a dreamed up portent of death. It represents the fictions of a Hollywood movie frontier. And yet the very best of Hollywood comes out in the characters and Siegel’s commitment to punchy, economical drama.

3.5/5 Stars

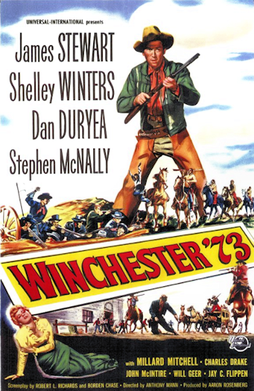

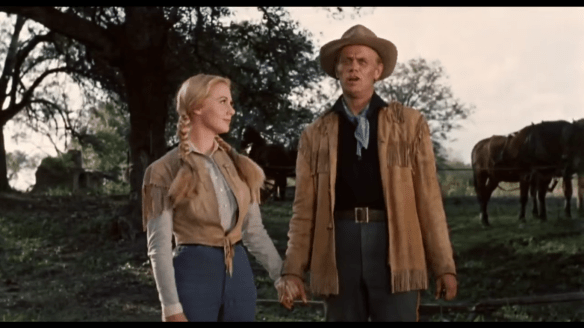

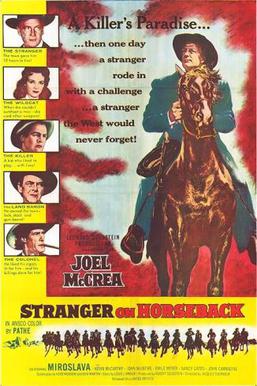

I didn’t know my Grandpa too well because he passed away when I was fairly young but I always remembered hearing that he really enjoyed reading Louis L’Amour. It’s not much but a telling statement nonetheless. I’ve read and seen Hondo (1953), which stars John Wayne and Geraldine Fitzgerald, and yet I’d readily proclaim Stranger on Horseback the finest movie adaptation of an L’Amour novel.

I didn’t know my Grandpa too well because he passed away when I was fairly young but I always remembered hearing that he really enjoyed reading Louis L’Amour. It’s not much but a telling statement nonetheless. I’ve read and seen Hondo (1953), which stars John Wayne and Geraldine Fitzgerald, and yet I’d readily proclaim Stranger on Horseback the finest movie adaptation of an L’Amour novel.