“I shall never forget the weekend that Laura died.” Those may have been the words of respected columnist and socialite Waldo Lydecker, but in truth they could just as easily be the words of a multitude of other players in the 1944 film Laura. The fact is, Laura not only casts a spell on everyone who happens to drift into her life, but she also captivates the audience who encounter her on the silver screen. She effectively reveals all their desires, obsessions, and shortcomings. In Laura, Otto Preminger conceived a wonderfully mysterious and enchanting film that constantly revolves around the life of this young woman. He utilizes his narrative, actors, cinematography, set design, and music in order to immerse his audience in this story. Preminger would ultimately create a hallmark in the film-noir genre of 1940s and 1950s, and it was Laura that also allowed him to truly realize his skill as a director.

In Laura the narrative is important but it is not paramount because there are some many other variables that work alongside the plot to make the film special. Realistically, this film can be split into two distinct sections since it begins in the present before flashing back and finally returning to the present once gain. Initially Lydecker is our narrator and he relates his former relationship with the deceased Laura to Lieutenant McPherson along with the audience. However, during the second half there is a shift which focuses on McPherson and his growing fascination with this woman he is investigating (emmanuellevy.com). The film takes a shocking about face when the presumed dead person suddenly turns up, all too alive and none worse for wear. However, with that suspense gone it seems only too probable that the film would lose some of its luster. After all there are numerous plot oddities that do not quite add up. As Roger Ebert once wrote, “Laura has a detective who never goes to the station; a suspect who is invited to tag along as other suspects are interrogated, a heroine who is dead for most of the film; a man insanely jealous of a woman even though he never for a moment seems heterosexual; a romantic lead who is a dull-witted Kentucky bumpkin moving in Manhattan penthouse society, and a murder weapon that is returned to its hiding place by the cop” (rogerebert.com). Ebert brings up some very concrete instances that might cause the audience to ask questions of the film. These are not the trademarks of a taut and revered classic after all, and yet it must be said that Laura works in spite of a sometimes questionable plot. French film critics Jean George Auriol and Jacques Doniol-Valcroze put it aptly when they wrote that “the fact that this is a crime plot is not important. Laura could equally well have been introduced into a film drama or a love story…The miracle is to have brought her to life” (rememberingninofrank.org). Furthermore, the magic does not simply disappear when we discover that Laura is not actually dead. It is a cumulative effect that the director Otto Preminger was able to build up for us.

Upon closer inspection there is a deeper significance to Laura than just its plot, because although it makes a good mystery, it is not altogether great. The actual brilliance of the film derives from something else entirely. First and foremost is the actual character of Laura played by actress Gene Tierney. Interestingly enough we do not see her in the present until the latter half of the film. Our only way of understanding her comes from the stunning portrait that hangs on her wall and the wistful recollections of columnist Waldo Lydecker. We are in the same shoes as McPherson (Dana Andrews) for the first half of the movie, as we try and piece together who Laura was. With McPherson the obsession goes so far that he actually falls in love with the image of this dead woman, in what would be a striking precursor to Alfred Hithcock’s own character study in Vertigo (emannuellevy.com). In fact, Lydecker goes so far as to call McPherson’s infatuation “warped” because the columnist believes that McPherson wanted her most when he knew that she was unattainable. In many ways she became his personal fantasy. For his part, Lydecker has his own fixation with Laura and he even tells her directly, “The best part of myself – that’s what you are. Do you think I’m going to leave it to the vulgar pawing… of a second-rate detective who thinks you’re a dame?” It seems like Lydecker almost envisions Laura as his personal creation because he endorsed her pen, introduced her to prominent people, and gave her a chance to succeed. Rather like the story of Pygmalion, he has tremendous feelings for her which quickly morph into jealousy when any other man gets close to her. He failed once to blow her head off with a shot gun and tries yet again only to slump to his death saying, “Goodbye, Laura. Goodbye, my love.” As a viewer his logic and actions do not make sense, but then again are any of the characters logical? Ms. Ann Treadwell on her part wants the one man who Laura is engaged to be married to, and she openly admits “He’s no good, but he’s what I want.” The only somewhat normal figure as far as desires goes seems to be Shelby Carpenter, who is Laura’s fiancée and Ann Treadwell’s romantic objective. However, on closer inspection even he has other needs which are met by Treadwell who gives him financial support. Amidst all of this we begin to wonder how Laura could have become involved with such “a remarkable collection of dopes” but perhaps they simply gravitate towards her, much in the same way the audience does.

It is a credit to Otto Preminger for making Laurasuch a fascinating and visually interesting film-noir. It is a film that exemplifies noir by taking typical motifs and putting a unique spin on them to further develop the genre. The sometimes confusing plot and nonlinear storytelling, which help develop the story of Laura, are typical elements of other films later on like The Big Sleep (1946). Furthermore, Preminger’s story of a man infatuated with a mysteriously beautiful woman is somewhat reminiscent of Fritz Lang’s Woman in the Window (1944). The difference with that film is that it all occurs in the mind of the protagonist. Laura actually plays out for real or at least we have no indication to believe that it is in fact a dream. The moment Laura appears in the flesh, in her front living room, it pretty much shocks us out of the dream that would be Woman and a Window and it quickly becomes certain reality. Sharp contrast cinematography is almost always essential to film-noir and Laura is no different. Often when a character enters a dark room, walks down a poorly lit street in the rain, or looks up at two figures in a window, the scene is a mix of chiaroscuro lighting, and pronounced shadows. However, perhaps just important as the lighting in Laura is the Mise-en-scene. Not only is every space developed extensively whether it is Lydecker’s bath or Laura’s living room, but numerous objects within these settings play key roles in the film. The portrait in Laura’s home has such a grander purpose in the entirety of the film, but it also fits as part of the decor. The identical clocks in Lydecker and Laura’s flats are featured prominently at the beginning and end of the film and they function as more than a piece of furniture. They reflect Lydecker’s affection for Laura but also his tendency towards distrust. They are pristine artifacts at the outset and yet by the end of the film one is busted open and the other is decimated by a shotgun. It also seems imperative to take a look at Lieutenant McPherson in comparison with other prototypical investigators in film-noir. In the beginning, he holds the characteristic cynical, tough as nails demeanor of a Sam Spade or Phillip Marlowe, and yet by the end of the film he leaves some of that behind him. He may smoke and drink incessantly but the simple fact that he fiddles with a puzzle to stay relaxed puts him in a different category than other film-noir protagonists. Laura on her part is difficult to classify as your typical femme fatale. However, in some respects she is a manipulator who puts men under her spell. Normally a femme fatale like Phyllis Dietrichson, Brigid O’Shaughnessy, or Gene Tierney in her role as Ellen Harland, manipulate men on purpose using their sexuality, wily charms, and power of persuasion. In Laura’s case it does not seem to be like this at all. It just happens, partially since she is such an innocent beauty, or maybe because she is an unattainable woman in a painting. When she is dead, she becomes a fantasy to be recalled and obsessed over, and yet she toys with her suitors in a way by coming back to life. Another prominent part of Laura is the score by David Raksin which in actuality is not present through the entire film. However, it creeps in at opportune moments when it is most needed and it effectively acts as a queueto the audience. Whether you hear Laura’s theme near the opening, on the radio, or by an orchestra at a party, the tune is the haunting essence of Laura herself and it reflects who she is even when she is not present, much like her portrait. To his credit Otto Preminger was able to put all these bits of inspiration together cohesively to make a seminal film-noir with its own set of strengths.

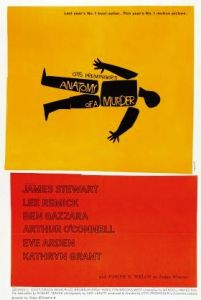

It appears safe to say that Laura was a spring board for the rest of Otto Preminger’s career, because he began as a producer and then emerged as a director who was adept at tackling complex and often controversial issues. During the 1940s and 50s Preminger kept on making film-noir including Fallen Angel, Whirlpool, and Where the Sidewalk Ends which continued his collaboration with Gene Tierney and Dana Andrews, although they never equaled his success with Laura (Wallace, 91). All throughout the rest of his career Otto Preminger would test the Production Code and Joseph Breen with various taboo topics. With The Moon is Blue, he faced opposition from the Breen Office for “sexual explicitness” (Wallace, 89). Soon he would direct both Carmen Jones and Porgy and Bess where he utilized all-black casts in both cases, which was unusual for the era (Wallace, 92). Next, came yet another controversial film in The Man with the Golden Arm where Frank Sinatra portrays a man struggling with drug addiction (Wallace, 92-93). Then, of course, there is Preminger’s classic, Anatomy of a Murder which revolves around a court case involving rape and murder. The often frank dialogue was revolutionary for the 1950s and it was bolstered by performances by James Stewart and George C. Scott who play opposing lawyers (Wallace, 93). His prominence may have dropped off somewhat after that, but it is undeniable that Otto Preminger was a directorial force from the 1940s well into the 60s and he can be acknowledged for pushing the boundaries of film content.

In Laura, Waldo Lydecker chides his companion for her “one tragic weakness.” As he sees it, for her, “a lean, strong body is the measure of a man.” Perhaps this does hint at the problem with all of Laura’s relationships, because each one has a superficial aspect. With Lydecker dead and no longer able to intercede, Laura walks off with McPherson, another one of these men with a “strong body.” As an audience we would like to see this as different from before but is it really? In the same way we too have one tragic flaw as well. To put it frankly we are human; humans with wants, desires, peculiarities, and emotions which are reflected and brought to the forefront by characters such as Lydecker, McPherson, Carpenter, Treadwell, and of course Laura Hunt. Whether he meant to or not Otto Preminger makes us face these issues through his film; however in the process he also develops a wonderful noir mystery that helped define the genre. It seems safe to say that Laura is a film-noir that is both stylish and witty, and at the same time haunting. Above all the film exhibits a “remarkable collection of dopes,” all tied to this enchantress named Laura. Every one believed they were “the only one who really knew her,” but every one of them, much like us, will never be able to quite figure her out. That’s the beauty of Laura, the character, and Laura,the film.

This is an Otto Preminger film about politics. That should send off fireworks because such a divisive topic is only going to get more controversial with a man such as Preminger at the helm — a man known for his various run-ins with the Production Code. All that can be said is that he didn’t disappoint this time either.

This is an Otto Preminger film about politics. That should send off fireworks because such a divisive topic is only going to get more controversial with a man such as Preminger at the helm — a man known for his various run-ins with the Production Code. All that can be said is that he didn’t disappoint this time either.