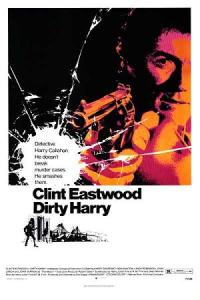

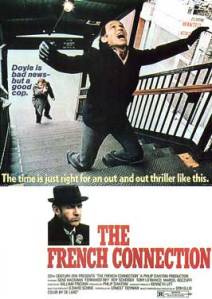

What makes Film-Noir intriguing is not simply the crime aspect but the fact that they are films with worldviews that are often weighed down by cynicism. Film-Noir depicts the harsh realities of human nature that few other films would ever dare to acknowledge onscreen. People are broken at their core; continually led to their own devices whether it’s greed or their own personal insecurities. These films give us a fascinating microscope by which to examine all the pain and prejudices that abound within the human condition. Samuel Fuller’s The Crimson Kimono (1959) shares some of these qualities, acting as a realistic procedural that employs cinematography and setting to say something about the world we live in. Furthermore, it has a remarkable stance on race relations, specifically for Japanese-Americans, that was ahead of its time and has hardly ever been matched.

What makes Film-Noir intriguing is not simply the crime aspect but the fact that they are films with worldviews that are often weighed down by cynicism. Film-Noir depicts the harsh realities of human nature that few other films would ever dare to acknowledge onscreen. People are broken at their core; continually led to their own devices whether it’s greed or their own personal insecurities. These films give us a fascinating microscope by which to examine all the pain and prejudices that abound within the human condition. Samuel Fuller’s The Crimson Kimono (1959) shares some of these qualities, acting as a realistic procedural that employs cinematography and setting to say something about the world we live in. Furthermore, it has a remarkable stance on race relations, specifically for Japanese-Americans, that was ahead of its time and has hardly ever been matched.

Through an analysis of The Crimson Kimono it becomes obvious that it is a striking film in the noir tradition, blessed with an urban realism that brings 1950s Los Angeles to life for us. As Samuel Fuller himself points out, “The thing that is most noir about Crimson Kimono…is how [he] shot it.” He was “in Little Tokyo and lots of other actual locations downtown, with cameras hiding in trucks, shooting at night with fast film because [he] could not put out lights” and as a result, the film has “a hard, gritty realistic look” (Film Noir Reader 3). When the action heads to the streets and hooker Sugar Torch is fleeing from an unseen assailant, it definitely has the gritty, atmospheric realism that Fuller was alluding to. This is a real place where we could be. These will be the same streets that Joe and Charlie will soon be hitting on their beat. Ironically, when Fuller shot the scene live he noted that he didn’t really “get much dramatic reaction.” Despite the fact that “An almost naked, six-foot-tall blonde is running for her life down the street,” nobody seemed to care and nobody looked (Film Noir Reader 3). That is the world of Los Angeles, full of indifferent masses that could care less whether something looks real or is real. It makes no difference to them because it fails to affect their existence. It is a dismal worldview, very representative of noir, but the odd thing is that Charlie and Joe are not like this at first. They are heroic, honest individuals with the duty of weighing through this noir world as part of their vocation. Thus, they oblige out of necessity and only then does it get to them. Even so, there is an argument that it is not the world, but their personal hang-ups that tear them apart.

Their investigation leads them to “Little Tokyo,” which becomes an integral locale within the context of the film and Fuller uses it effectively. For instance, in one scene Joe walks the streets with a Mr. Yoshinaga after meeting him at a cemetery. It’s a highly mundane moment and yet Fuller still manages to make it interesting. It is also less austere than the earlier scene of Sugar’s murder since banners are flying and locals are milling about the storefronts. That’s why it becomes an interesting setting for a chase sequence, taking the everyday environment and turning it into a point of drama. It reinforces the fact that Fuller seems to be more interested in the realism of common incidences compared to high drama. It’s almost as if he’s a journalist again trying to get a juicy feature story. It’s ordinary, real and it meets people where they are at.

One of the most significant moments occurs later on during the kendo match where Joe and Charlie are supposed to face off as part of the Nisei Week Festival. It’s a big deal and flyers are plastered all over the town so people will turn out for the event. Within the context of the film, it matters on several levels. The fact that Charlie is Joe’s equal suggests that martial arts are not just stereotypically Asian, but they can be universal. Perhaps most importantly their bout reveals the descent of Joe into utter resentment because he disregards all the traditions of Kendo and begins to go after his friend with a vengeance. It’s the turning point that Charlie cannot forgive Joe for and for good reason. The sequence plays out as quick cuts between masked faces, swords, dancing feet, and exuberant onlookers. Practically before we know what has happened Joe begins beating Charlie over the head and lays him out. It is such a rapid about-face that is underlined by Joe’s own insecurities, which we will get to delve into later.

The culmination of the film occurs during the festivities, with music, dancing, banners, lanterns, and girls in kimonos. It seems fitting that Fuller’s entire story leads us to this point at such a public place full of your usual bystanders. It’s theatrical while still maintaining a sense of the real world. Here again, we have a third chase scene except this time Fuller does something especially interesting with the music. During the pursuit there is a symphony of conflicting tunes going on between the bands: “One plays classic music, one plays Japanese music, one plays hot music, and so on. Whenever [Fuller] cut from the killer to the pursuer, the music changed. That gave [him] the discordant and chaotic note” that was desired (The Director’s Event). It seems like such a simple detail and yet it truly is clever in conception, because it adds another layer of realism to the scene while simultaneously utilizing diegetic sound for dramatic effect. It could be implied that the music also reflects Joe and Charlie’s own feelings of confusion and friction, which injured their friendship and Charlie’s ego. It’s ultimately Joe who has to parse through all the noise and commotion ultimately finding the truth. It’s no small coincidence that once again we find ourselves on the urban streets at night just like when Sugar Torch was gunned down. Fuller parallels that earlier scene and yet so much has changed. This time around there is a hint of hope, but a sour taste is still left in the mouth. It suggests that you cannot fully escape the darkness and anxieties that seem to engulf us because this world can never truly have a perfect ending.

Fuller’s film has murder attempts, gunshots, fist fights, etc. However, he knows how to simplify scenes getting only the necessary elements out of them. When Sugar Torch crumples to the ground we hear the shot and that’s all we need. When an attempt is taken on Chris’s life we see the gun pointed ominously and again we hear the shot but that’s all. There’s a cut to a new scene and Fuller gives us all the details we need to know. In a sense, it’s about an economy of images that allow this film to be short, at only 78 minutes, and still, pack a punch. It definitely was out of necessity that Fuller did many of these things which would have saved time and money, but it also undoubtedly caused him to come up with creative solutions. The Crimson Kimono like many of Fuller’s films is hardly sleek or polished and that is part of the allure. It is the opposite of typical Hollywood and it fits film-noir so beautifully. It has the same harshness as one of Fuller’s other works Pickup on South Street (1953). What it lacks in a femme fatale or Cold War sentiment, The Crimson Kimono makes up for in how it tackles romance and the job of a policeman with a subtle touch. For this reason, it may be less of a film-noir than Pickup and perhaps a lesser film, but there is still power in its story and the racial lines that it willfully challenged. It also seems necessary to acknowledge a bit of Samuel Fuller’s background, because it further influenced his filmmaking. He came from a Jewish family in New York and dropped out of school to write for a newspaper along with penning pulp fiction novels. He served during WWII and when he came back he began a storied career as a writer and director of frequently subversive “B pictures.” His versatility is especially remarkable, cycling through all types of films from westerns, to crime films to war dramas, elevating them above “B” quality. Part of the reason is that he never gave into conventions and his genuine depictions of race in films like The Steel Helmet (1951), Run the Arrow (1957) and The Crimson Kimono were ahead of their time. The Crimson Kimono is an extraordinary film historically because it depicts something that we very rarely see, especially for 1959. The late, great actor James Shigeta portrayed the straight-laced policeman and former Korean War hero named Joe Kojaku. He’s a sympathetic figure and hardly a caricature. His best friend is the Caucasian Charlie Bancroft (Glenn Corbett), who is on the LAPD with Joe and a war buddy. They are inseparable and they share a flat. Above all, the most amazing thing is that Joe gets the girl over his friend! That might be a small victory, but I have seen a lot of films to know that the Asian guy never gets the girl, especially if she is Caucasian. Sam Fuller subverts the norm and it is a major statement on interracial romance in an age when many would have scoffed at it. However, Fuller also takes immense care to look at both sides of the equation, and he allows both men the benefit of the doubt. Joe must figure out his own identity even acknowledging, “I was born here. I’m American but what am I? Japanese, Japanese American, Nisei? What label do I live under?” The question is not an easy one and it is one that he struggles with over the course of the entire film, navigating his feelings towards Charlie and then the beautiful artist Chris (Victoria Shaw).

The Crimson Kimono is an extraordinary film historically because it depicts something that we very rarely see, especially for 1959. The late, great actor James Shigeta portrayed the straight-laced policeman and former Korean War hero named Joe Kojaku. He’s a sympathetic figure and hardly a caricature. His best friend is the Caucasian Charlie Bancroft (Glenn Corbett), who is on the LAPD with Joe and a war buddy. They are inseparable and they share a flat. Above all, the most amazing thing is that Joe gets the girl over his friend! That might be a small victory, but I have seen a lot of films to know that the Asian guy never gets the girl, especially if she is Caucasian. Sam Fuller subverts the norm and it is a major statement on interracial romance in an age when many would have scoffed at it. However, Fuller also takes immense care to look at both sides of the equation, and he allows both men the benefit of the doubt. Joe must figure out his own identity even acknowledging, “I was born here. I’m American but what am I? Japanese, Japanese American, Nisei? What label do I live under?” The question is not an easy one and it is one that he struggles with over the course of the entire film, navigating his feelings towards Charlie and then the beautiful artist Chris (Victoria Shaw).

Regrettably, posters for this film were highly shallow and sensational reflecting the age with taglines like “Yes, this is a beautiful American girl in the arms of a Japanese boy!” or “What was his strange appeal for American girls?” It places this character in the typical category of an exotic lover. He’s not a real man, only an enticing mysterious foreigner with strange appeal. Likewise, the title Crimson Kimono itself brings to mind oriental exoticism involving strange dress and foreign culture. This could have just as easily been a dated film of yellowface and Asian stereotypes, but it’s superfluous to judge this film by its posters and title alone. When you actually watch Fuller’s work these are not the focal points at all. As Fuller later said himself, “The whole idea of [his] picture is that both men are good cops and good citizens. The girl just happens to fall in love with the Nisei. They’ve got chemistry” (A Third Face). Chris likes Joe because he is a genuine hero, not because the other man is not. Joe is sweet and shares a love of art (piano and painting) like her. She could care less that he’s Asian just like Charlie could care less. Those are the kind of people they are.

Regrettably, posters for this film were highly shallow and sensational reflecting the age with taglines like “Yes, this is a beautiful American girl in the arms of a Japanese boy!” or “What was his strange appeal for American girls?” It places this character in the typical category of an exotic lover. He’s not a real man, only an enticing mysterious foreigner with strange appeal. Likewise, the title Crimson Kimono itself brings to mind oriental exoticism involving strange dress and foreign culture. This could have just as easily been a dated film of yellowface and Asian stereotypes, but it’s superfluous to judge this film by its posters and title alone. When you actually watch Fuller’s work these are not the focal points at all. As Fuller later said himself, “The whole idea of [his] picture is that both men are good cops and good citizens. The girl just happens to fall in love with the Nisei. They’ve got chemistry” (A Third Face). Chris likes Joe because he is a genuine hero, not because the other man is not. Joe is sweet and shares a love of art (piano and painting) like her. She could care less that he’s Asian just like Charlie could care less. Those are the kind of people they are.

Fuller’s depiction goes both ways, however, because while he never sells Kojaku short, he also suggests that Joe might be part of the problem. Fuller notes that he “was trying to make an unconventional triangular love story, laced with reverse racism, a kind of narrow-mindedness that is just as deplorable as outright bigotry. [He] wanted to show that whites aren’t the only ones susceptible to racist thoughts” (A Third Face). This ends up happening with Joe since he gets so caught up in prejudice, his own prejudice, that it wrecks his relationships with his friend. Charlie is not angry because Joe, an Asian, stole his girl. Charlie is understandably irritated because his best friend took the girl who he really liked without telling Charlie his true feelings. Joe makes the mistake of attributing this to a question of race, but Charlie, like Fuller, is not that shallow. His reaction is purely a human reaction that develops in any romance when two men who are equals go after one girl and only one can come out on top. It hurts no matter what race, color or creed they are. That’s just the reality and that’s the lesson that Joe does not understand at first. He seems to care too much about the race question and potentially even his identity. It ultimately damages his relationship with Charlie and we cannot know for sure if it will ever be repaired, even if we would like them to patch things up. Thus, Fuller combats racism from both angles, including minorities who might take on the role of a victim too quickly. Because the reality is, issues of race almost always get blown way out of proportion with both sides being hypersensitive. Fuller seems to have the right handle on the situation, not stooping to unwarranted stereotypes and not heaping all the blame on the majority. Sometimes everybody is at fault at least a little bit. That’s simply how life is and that’s how it gets depicted in The Crimson Kimono, with a sensitive, albeit, realistic touch. Furthermore, one could argue that it is a typical noir ending because although Joe still gets the girl it came at a steep cost. The Crimson Kimono is riveting from the beginning because it is such a groundbreaking and rare piece of film history. It presented on film something that we never see or very rarely see: a relationship between an Asian man and Caucasian woman. In the hands of Samuel Fuller, this unique but still mundane tale is kept thoroughly engaging. He infused his screenplay with visuals of Los Angeles and realism that makes his characters all the more believable. His camera is able to take the everyday and make it dramatic while we continue to invest in these people. It seems fitting to end the discussion with a quote from the man himself. He affirmed that “One film never really gives me complete satisfaction. Nor should it. All creative people must learn how to deal with the imperfect and the incomplete. There is no end in art. Every accomplishment is the dawn of the next challenge.” That’s what makes the films of Samuel Fuller meaningful. No one film can ever have everything. The Crimson Kimono does not have every answer on race and it certainly does not have every convention of film-noir. It’s imperfect, but it is a jumping off point for future endeavors and dialogue.

The Crimson Kimono is riveting from the beginning because it is such a groundbreaking and rare piece of film history. It presented on film something that we never see or very rarely see: a relationship between an Asian man and Caucasian woman. In the hands of Samuel Fuller, this unique but still mundane tale is kept thoroughly engaging. He infused his screenplay with visuals of Los Angeles and realism that makes his characters all the more believable. His camera is able to take the everyday and make it dramatic while we continue to invest in these people. It seems fitting to end the discussion with a quote from the man himself. He affirmed that “One film never really gives me complete satisfaction. Nor should it. All creative people must learn how to deal with the imperfect and the incomplete. There is no end in art. Every accomplishment is the dawn of the next challenge.” That’s what makes the films of Samuel Fuller meaningful. No one film can ever have everything. The Crimson Kimono does not have every answer on race and it certainly does not have every convention of film-noir. It’s imperfect, but it is a jumping off point for future endeavors and dialogue.