On a superficial even subliminal level, La Piscine (The Swimming Pool in English) shares some nominal similarities with The Swimmer and The Graduate. Certainly, drawing the connections isn’t too difficult.

On a superficial even subliminal level, La Piscine (The Swimming Pool in English) shares some nominal similarities with The Swimmer and The Graduate. Certainly, drawing the connections isn’t too difficult.

It’s a mood and a feeling as much as it is subject matter. We open on a rural villa in the French countryside with a veranda and a swimming pool. Perfect for lounging. There we find France’s great Adonis-turned-action hero Alain Delon.

He already gave his audience a taste in glimmering fare like Purple Noon, but he’s the personification of disaffected cool, and it’s little different in Jacques Deray’s film.

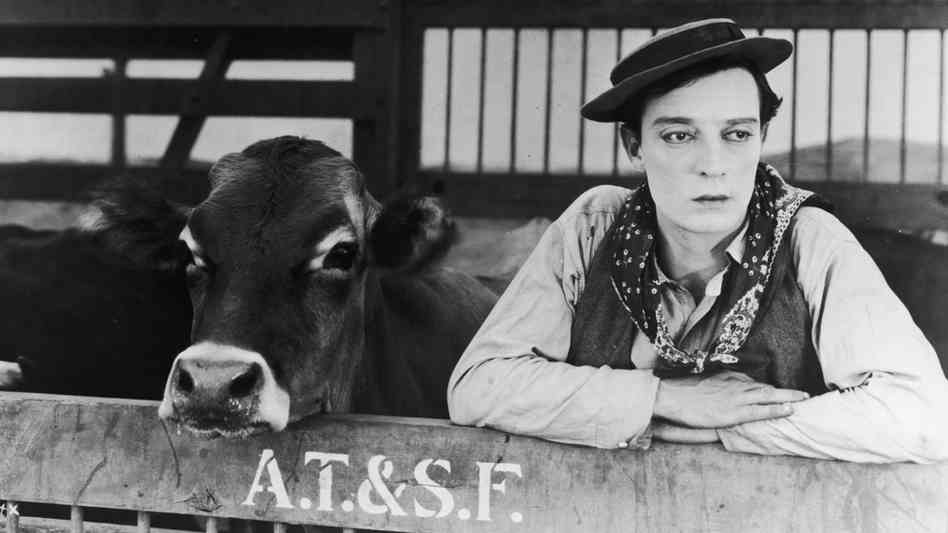

What’s developed in the first idle moments of the movie is this splendorous sun-soaked aesthetic. It’s akin to Benjamin Braddock floating in his parent’s pool or Burt Lancaster in his short cutoffs journeying from pool to pool in East Coast WASP country.

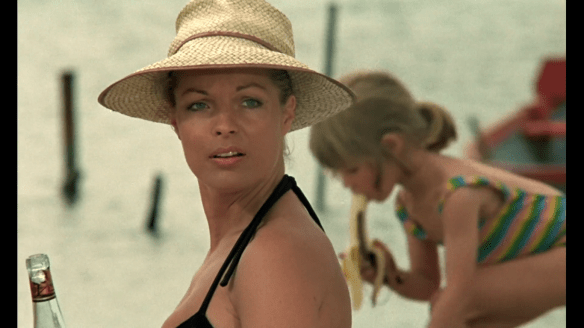

Jean-Paul (Delon) is at the tranquil getaway with his current lover Marianne (Romy Schneider), and it’s apparent they are in the frisky honeymoon stage full of delirium and amour. Viewed from the outside, the two stars feel like a European “It” couple though they hadn’t been officially together since the beginning of the decade.

Their auras are too big not to still associate their scintillating stardom. The movie relies on it heavily, and it’s quite effective. Because they are effective as the definition of intercontinental movie stars. You’d be hard-pressed to find two more photogenic people than Delon and Schneider.

Within the film, there’s no sense of how they came to own this property, but it’s a non-factor in the story. We come to accept their idleness, the fact that their housekeeper brings them breakfast on trays, and they have the complete freedom of the place be it sleeping in, languishing in the noonday sun, and really doing whatever they please. It’s a state of mind for the movie.

In such a space it becomes a question of what can happen and what will upend and break through the reverie. Our first signs of life come in the form of an old friend named Harry (Maurice Ronet) who makes an auspicious entrance.

He’s a bit of a ne’er-do-well, likable, but roguish, and difficult to pin down. He hardly seems the domestic type, and there’s a sense that he’s always on the run, chasing after the next adventure and fling. Maintaining his personal freedom at whatever the cost. What’s the most surprising is he’s brought his aloof teenage daughter Penelope (Jane Birkin) along.

As someone always trying to hang onto the capriciousness of youth, he’s not the kind of person you expect to have a child; there’s some mention of her mother being a British girl he had relations with, but he’s not so much a parental influence as he is a companion. Mostly he just seems proud that she’s beautiful, and it’s fun to brag to his friends about her.

Critical to the film, he also had a past relationship with Marianne. How could he not, but then again, that was many years ago, and she’s now in love with Jean-Paul. It doesn’t take radar to recognize what might conceivably happen since it’s the ’60s and beautiful people are involved. It’s no coincidence Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice came out the same year.

True to form, Harry is the life of the party, and he always races off in his Maserati and comes back whenever he pleases; one night he comes with a gang of young bohemians in tow. He terms them his “bosom buddies,” and they dance the night away.

It becomes a point of friction watching who everyone spends most of the night with. We see potential trouble from a mile away as they link up and an inkling of jealousy begins to seethe under the surface.

What a strange little family they make. One evening they sit down for a dinner of Chinese food of all things. Marianne and Harry went to town together — a perfectly romantic getaway — and Jean-Paul took Pen away to the sea.

Whether or not it’s an act of retaliation or not, it’s easy to perceive it as such. They sit around working their chopsticks, fidgeting, and trading glances. If the movie is about something it would be this. The elephant in the room as it were.

However, there is a lack of an interior when you break the film open and that’s part of what puts it below its contemporaries, at least in my estimation. There are gorgeous exteriors with gorgeous people, fabulous sartorial style, and not much else.

It’s a testament to the performers and their innate charisma because they make it compelling. But it lacks the kind of commentary or wit of The Graduate or even the fabular qualities of The Swimmer.

The final act of La Piscine takes it into the territory of a true thriller. For the first time, something happens that might have its place in a Henri-Georges Clouzot picture or even Jean-Pierre Melville. Until this dramatic inflection point, it’s a work of latent psychology and desire. I’m not sure if the shift is warranted or not.

However, there is something else worth noting. As of 2024, Alain Delon was still with us, but all his primary scene partners are all gone. Birkin died most recently in 2023, and both his friends, Romy Schneider and Maurice Ronet, were lost to us too soon.

This realization adds a different kind of knowing austerity to the proceedings, though it’s hardly required. Even without this insider information, we leave the film mostly empty, and it’s difficult to know whether this is a statement or merely a formalistic reality.

3.5/5 Stars

Note: This review was written before Alain Delon’s passing on August 18, 2024.

Citizen Kane is so often lauded for the simple fact that never before had a director had so much creative control on a project and exercised it in such an unprecedented fashion, especially given the state of affairs in the Hollywood studio system. It’s an enigma, a stunning debut and really an astounding miracle where all things aligned for an instant of so-called perfection.

Citizen Kane is so often lauded for the simple fact that never before had a director had so much creative control on a project and exercised it in such an unprecedented fashion, especially given the state of affairs in the Hollywood studio system. It’s an enigma, a stunning debut and really an astounding miracle where all things aligned for an instant of so-called perfection. At first glance The Trial is a bare-boned parable, feeling gaunt and cavernous with empty sets and even emptier words. Everyone Josef meets talks him in circles, tirelessly — never leading to any significant conclusion, only the next diversion in his journey.

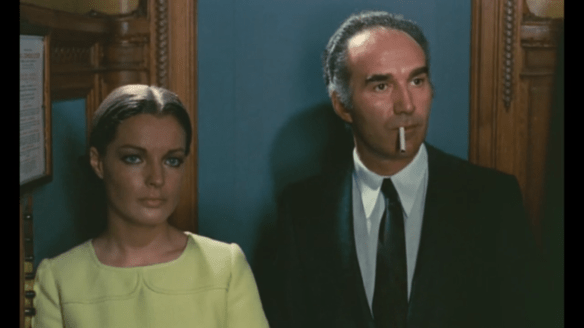

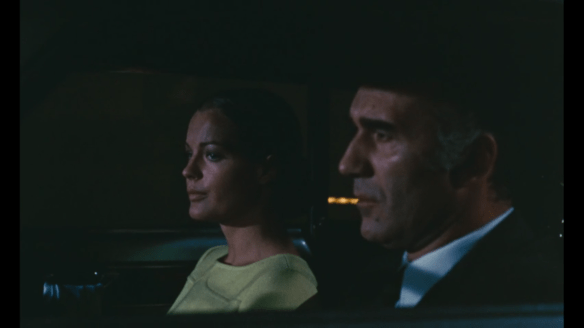

At first glance The Trial is a bare-boned parable, feeling gaunt and cavernous with empty sets and even emptier words. Everyone Josef meets talks him in circles, tirelessly — never leading to any significant conclusion, only the next diversion in his journey. If The Trial is a hodgepodge of talent, with the presence of Americans Orson Welles and Anthony Perkins, international sirens Jeanne Moreau, Elsa Martinelli and Romy Schneider, with European backing and source material from Kafka, then it is a thoroughly intriguing marriage all the same. This film is perhaps the greatest adaptation of the work of Kafka and not due necessarily to its faithfulness to its source material, but because it displays an unmistakably Wellesian vision. The cyclical nature of the legal system pales in comparison with the fascination that comes with watching the continual creativity that is projected up on the screen — this is a hollow dream of a film.

If The Trial is a hodgepodge of talent, with the presence of Americans Orson Welles and Anthony Perkins, international sirens Jeanne Moreau, Elsa Martinelli and Romy Schneider, with European backing and source material from Kafka, then it is a thoroughly intriguing marriage all the same. This film is perhaps the greatest adaptation of the work of Kafka and not due necessarily to its faithfulness to its source material, but because it displays an unmistakably Wellesian vision. The cyclical nature of the legal system pales in comparison with the fascination that comes with watching the continual creativity that is projected up on the screen — this is a hollow dream of a film.