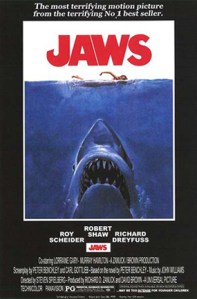

I remember my dad telling a story about the first time he saw Jaws back in 1975, now 50 years ago. He was on a road trip visiting a childhood friend in the Midwest, and though he had spent all his life in California, he was grateful to be in a place that was landlocked when the movie came out.

If my dad was representative of the general populous, this reaction was not unusual, and for any number of reasons, Jaws was a true cultural phenomenon. It changed the playbook of what a movie could be as a summer blockbuster, even as Steven Spielberg willfully built off the formula of Alfred Hitchcock while bringing his own youth and flair for storytelling to the fore.

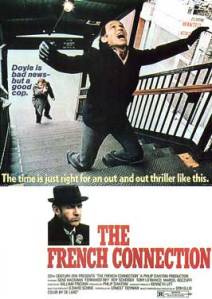

It struck me watching the film this time how it is really split into two sections. There are the scenes in the island getaway town of Amity where Police Chief Martin Brody (Roy Scheider) is introduced as a New York City transplant (Coincidentally, it’s convenient to read The French Connection as a bit of backstory). We soon get a sense of his family life, his happy marriage with his better half (Lorraine Gary), and the small-time responsibilities that come with the incoming tourist trade. He also hates the water…

These are the throes of summer, on the verge of the July 4th weekend, and a town like this thrives and even relies on out-of-town business. The first inkling of a shark attack comes when the mangled body of a young woman is found washed up on the shore.

Then, there’s the moment for all time when Brody tries to relax in the arms of his wife on the seashore, only to see an ominous creature emerge from the water and confirm all his worst fears.

A friend pointed out how Spielberg pays homage to Hitchcock with the “Vertigo Effect” or dolly zoom, which gives us as an audience such a perturbing sensation as we are physically reeled into the moment. From then on, it’s not just a threat, but a battle that Brody must wage, dealing with the local repercussions, backroom politics, and general hysteria that gets dredged up in the face of such a news story. As the police chief, it feels like the weight of the whole fiasco falls on him, and what’s worse is that he has so little support.

It all comes to a head when a grieving mother (Lee Fierro) confronts him with a public slap to the face: She found out he knew about the shark threat, and he still kept the beaches open. We know what actually happened, but still, as a beacon of safety, it falls on him, and he internalizes the outrage. Because he has a conscience and a family, too.

Then there are the later scenes where three men go out on a mission to hunt down the Great White terrorizing the town. It is an elemental story of man vs. nature. The cast thins out with the three primary stars and a big shark playing out a game of cat and mouse on a boat against a vast ocean. It’s an isolating, harrowing undertaking.

Put in these terms, and it feels like an entirely different movie, and yet there’s not a moment when they don’t feel anything but intimately related. A lesser film would have simply shot the second part — extended it — added some more sharks, guts, and explosions, and made it the movie (I haven’t seen the Jaws sequels, so I’m not sure if this formula applies). Although I’m sure this is what drew Spielberg to Peter Benchley’s source material.

However, this movie is made better by how it builds out an entire world, and we see how it develops the context and creates the stakes and emotional resonance for the entire story.

Scheider is also the only one who can kill that shark in the end. He moved away from the urban jungle to have a quieter life. But the movie calls for him to face this threat head-on, and he does it in an extraordinary way, aided by Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw’s characters.

They both provide two sides of an ethos appeal that lend credence to the evolutionary brutality of this underwater leviathan. Because one represents youthful intellect and scientific know-how of an oceanographer, while the other is a veteran of the sea, grizzled and tenacious. But we know intuitively that the trajectory of the story revolves around Scheider coming face to face with his own fears. It’s inevitable. No one else can save him.

These words don’t always go together, but Jaws has some delightfully effective expositional scenes. I think of the opening hook where a bunch of young people are on the beach mingling together. The eyes of a young man and woman meet. Then, the camera pulls away as they have their meet-cute. We understand everything without hearing, and the next thing we know, they’re racing off toward the water to skinnydip…

There’s also the scene where oceanographer Matt Hooper (Dreyfuss) pays a house call. It’s been a tumultuous day, and the police chief has grown introspective, jaded by the day’s events. Hooper awkwardly has two bottles of wine, and he’s wearing a tie. It becomes a scene with the wife talking to the young man, and we learn about both of our leads with this lovely sense of organic humor.

Then there’s Quint’s moment on the boat one evening, recounting his harrowing experience on the U.S.S. Indianapolis in 1945 on a mission related to the atomic bomb. Ultimately, they were sunk, and many of the survivors were picked off by swarms of sharks in the ensuing hours. An event like that forms a man for life.

Moments like these are chilling and give the moments of levity even more import. It’s like an escape valve for the tension. Spielberg does an admirable job of choreographing the hubbub of the town with frantic conversations and characters speaking over one another in a manner mirroring real life.

In another scene, Brody is deep in his thoughts, obviously distressed, then, right next to him at the dinner table, his little boy mimics his every move. It’s such an endearing moment of childlike warmth and affection. Or later, a drunken Shaw and Dreyfuss partake in some one-upmanship as they trade tattoo stories gaily after being at one another’s throats for most of the journey.

Spielberg, at such a young age, already feels adept at creating a total immersive experience in film (You only have to look at his work on Columbo and Duel to see the work he put in before Jaws).

The underwater POV shots from below as human bodies tread above the waterline draw us in, and the notes of John Williams’ score never cease to cause my feet to tense up in my shoes. There are even jump scares I had forgotten about. The cumulative effect is still overwhelming.

There’s an extraordinary blending of visual compositions that tell us the story succinctly, sprinkled with the kind of humor, exposition, and personal conflict that give the broader drama of Jaws a genuine meaning. Because we are not animals; we are not evolutionary machines. We are embodied creatures. We have hearts, limbs, eyes, voices, and feelings that make us who we are. It’s difficult to extricate ourselves from these realities, and what kind of unfeeling Social Darwinism would that leave us with?

The Mayor (Murray Hamilton) is a character who is easy to dislike. He does come off as a kind of irrefutable sleaze, and yet when he visits the hospital to give his condolences and reluctantly sign off on Quint’s hunt, he finally makes an admission. His kids were on the beach too, where the attacks happened. For a moment, he is as human as anyone else.

Because he’s emblematic of a story about locals trying to protect a way of life, and outsiders trying to maintain their own lives somewhere new. It’s a pleasure to watch Jaws and see it not simply as a historical lodestar in the blockbuster age, but 50 years on, it still remains a captivating saltwater thriller showing a young up-and-coming filmmaker on the ascendancy.

I’ve rarely seen my dad set foot in the ocean during my lifetime. It’s probably coincidental, although Steven Spielberg (and John Williams) might have something to do with this, too.

5/5 Stars