The great thing about The Big Three — Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd — and all the great silent clowns, is how they engender a kind of audience identification with profoundly comic results. Because each had their own unique persona that remained constant throughout all the trials and tribulations they went through.

The great thing about The Big Three — Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd — and all the great silent clowns, is how they engender a kind of audience identification with profoundly comic results. Because each had their own unique persona that remained constant throughout all the trials and tribulations they went through.

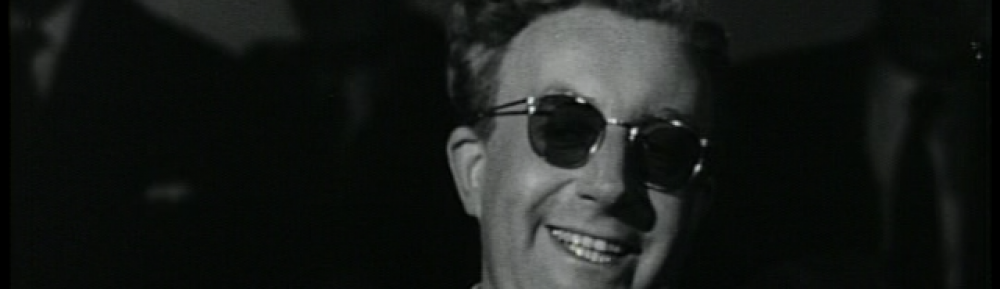

The enduring charm of the Harold Lloyd character is his nebbish yet indefatigable spirit. He’s bespectacled, always smiling, and there’s a bit of a hapless daredevil in him. He doesn’t always do so purposefully, but he’s accustomed to ticking clocks — racing against time against the odds — and of course Safety Last famously put him in contact with another literal ticking clock. More on that later.

At only 73 minutes, it’s easy to place a silent comedy like Safety Last with other rudimentary forms of movies from the nascent film industry. The two reelers and other silent fare which might seem like a dime a dozen and disposable. We might mistakenly think we have nothing to learn from them because they are over a century old and we’ve already grown beyond what they have to offer.

And yet the very first shot belies any erroneous impressions. There’s the shadow of what looks to be a hangman’s noose. Our hero, Harold, looks to be behind bars saying a last adieu to the love of his life. Then, the perspective shifts and we realize not a man shuffling off to jail but one waiting at the train station to head to the city to make good. Eventually, his girl Mildred can come out to him and they can get married!

There’s not a specific utility to the gag and if you’re not thrown off by it tonally, it shows a sense of visual invention that easily transfers from early shorts and reel comedies. It shows these early movies were not made by a bunch of hacks but technicians with a great deal of ingenuity and knowhow. The proof is in what they left us.

The first half of the picture is most defined by its bits. There’s a gag to avoid the rent collector where Harold and his roomie hide under their hanging coats with their legs pulled up.

In another vignette Lloyd is stuck in the back of a laundry truck baking like a sauna with a driver who is deaf; it leads into his extended attempt to get back to his work in time by any means necessary so he can clock in. It’s to no avail so he sneaks in under the guise of a mannequin, as one does. No one can say he’s not plucky.

We can all commiserate with him as he deals with time wasters on the department store floor and then the hordes of blue-blooded ladies who come for a sale prepared to pull the clothes off his back; some things haven’t changed. There’s another scene where he combs his hair in the shine of a bald man’s pate. Again, it’s yet another whimsical example of ways to stretch the form for the sake of a visual gag.

Then, Harold tries to put on airs for his girl masquerading as the general manager, though he’s only a mere grunt who’s easily discarded. Like us all he wants to be important and appreciated; he doesn’t want to let his loved ones down or be seen as a failure.

The final act of climbing all 12 floors of the department store feels like the birth of the high-wire thriller genre before our eyes. After all, he’s as much of a free climber as you or me. Still, he has that smiling girl in the back of his mind and the prize money if he reaches the top.

There’s some visual trickery but the cutaways and overhead shots give us a sense of scale all in service of the movie. The fact we can’t make out all the fault lines and there is still this harrowing sense of unassailable danger is a credit to the picture a century on. Both as a physical feat and a technical marvel of early Hollywood.

Harold’s conspiring with his acrobatic friend to get up the building devolves into a charade with cops and a drunk, a bit like a Keystone Kop reel with chases and “Kick Me” signs. It might be the lowest common denominator of comedy, but that’s hardly a bad word.

Lloyd has a myriad of gags at his disposal as he begins his ascent. They are play things that complicate what already feels like a daunting task: pigeons, scurrying mice, rope, a spring, and of course that famed clock face.

Lloyd clinging for his life has become one of the most iconic images in cinema history, and that’s across the board regardless if people have ever seen the movie or not. His exploits live on in the ubiquity of the public consciousness.

My final observation is noting how the movie ends with a gag just as it came in. His shoes get stuck in the tar on the rooftop as he walks off with his girl, the always and forever irrepressible hero Harold Lloyd.

There’s an added layer to the silent movie romance when you realize Lloyd would actually marry his leading lady Mildred and they would be together for the rest of their lives. It’s a stretch but it’s hard not to see how this big smash of a movie was to the actor Harold as climbing the department store was to his alter ego. They came out on the other side larger than life and beloved by the public. Most importantly, they got the girl. It’s the stuff of Hollywood.

4.5/5 Stars

“Go West Young Man. Go West.” – Horace Greeley

“Go West Young Man. Go West.” – Horace Greeley

Though the image quality of the print I saw hardly stands the test of time, there’s something almost modern about The Virginian’s characterizations or at least what it deems interesting to show.

Though the image quality of the print I saw hardly stands the test of time, there’s something almost modern about The Virginian’s characterizations or at least what it deems interesting to show.