A place with a name like Okefenokee feels immanently American and this is an inherently American story though expatriate Jean Renoir feels sympathetic to these types of folks. He wasn’t a working-class filmmaker but in movies from his home country like Toni or La Bete Humaine, you see his concern for people in this station of life. They work in the fields, on the trains, making a good honest living, and sometimes their existence gets disrupted.

Granted, it’s early in his career trajectory, but it flabbergasted me that Dana Andrews is billed fourth. His Ben Ragan is our most obvious protagonist as an obdurate young man aiming to get his lost bloodhound back from the nearby quagmire of Okefenokee swamp, a cesspool of gators and crosses mounted with skulls. Worse still, it’s said to be the hiding place of wanted mankiller: Tom Keefer (Walter Brennan).

Ben’s father is an ornery old cuss named Thursday (Walter Huston), who remarried a younger woman. She’s a sign that he can be an affectionate man; he just has a difficult time showing it to his son.

Given these origins in a real place, I’m thoroughly intrigued by the world especially because it wasn’t completely fabricated on a studio backlot but was shot on location. This level of mimesis blends actors we know from all the Classic Hollywood projects with something that lends itself to greater authenticity. It’s not stark realism, but it adds a layer of tangible reality to the picture aside from some unfortunate back projections.

When Ben goes in search of “Old Trouble,” he sounds his horn like the Israelites marching around Jericho. Instead, he finds Walter Brennan who comes off like a fugitive mountain man with almost shamanistic qualities. Nothing can bring him down; not even a cottonmouth. But he also carries the film’s core dilemma with his fate. The town wants to string him up for killing a man; he pleads his own innocence, and Ben must for the time being keep his secret.

Swamp Water doesn’t get much press and The Southerner is usually touted as Renoir’s best American offering, but the link between the two pictures seems increasingly evident. The film has some of the same pleasant surprises. Some people are a whole lot better than you think they are and some are a whole lot worse.

The mercantile where Ben sells his furs is full of a gang of actors you relish seeing in these old Hollywood productions. Their prevalence is only surpassed by their instant recognizable character types. I’m talking about the Ward Bonds, Eugene Palletes, and Guinn ‘Big Boy’ Williams.

Whether John Ford got it from Renoir or Renoir got it from Ford, they both seem to have this enchanting preoccupation with dance even if it’s merely on a subconscious level. With The Grapes of Wrath and Swamp Water or The Southerner and Wagon Master we see firsthand how these communal events engender personal connections between the masses.

Except in a small outpost like this, they also bring all the local feuds and all sources of gossip to the surface. Ben’s flirtatious beau (Virginia Gilmore), comes off a bit like a blonde Jane Greer, albeit with a lightweight spitefulness. In contrast, Anne Baxter owns a curious role as a near-mute social pariah thanks to the notoriety of her fugitive father.

Rebuffed by his own girl, Ben vows to bring the ostracized (Baxter), now gussied up and quite presentable, to the gathering. It’s a bustling dance floor of dosey-does which is just as easily replaced by fisticuffs. It doesn’t help that Mr. Ragan is intent on searching out the man who accosted his wife, and he’s not squeamish about making a scene.

But beyond this, the Ford and Renoir connection can be seen in the stable of actors shared between Ford’s usual company and this 20th Century Production. It’s easy to say most of this falls to coincidence. This might be true, but in men like Walter Brennan, Ward Bond, and John Carradine, there’s something intangible we might attribute to the characters at the forefront of both these directors’ works.

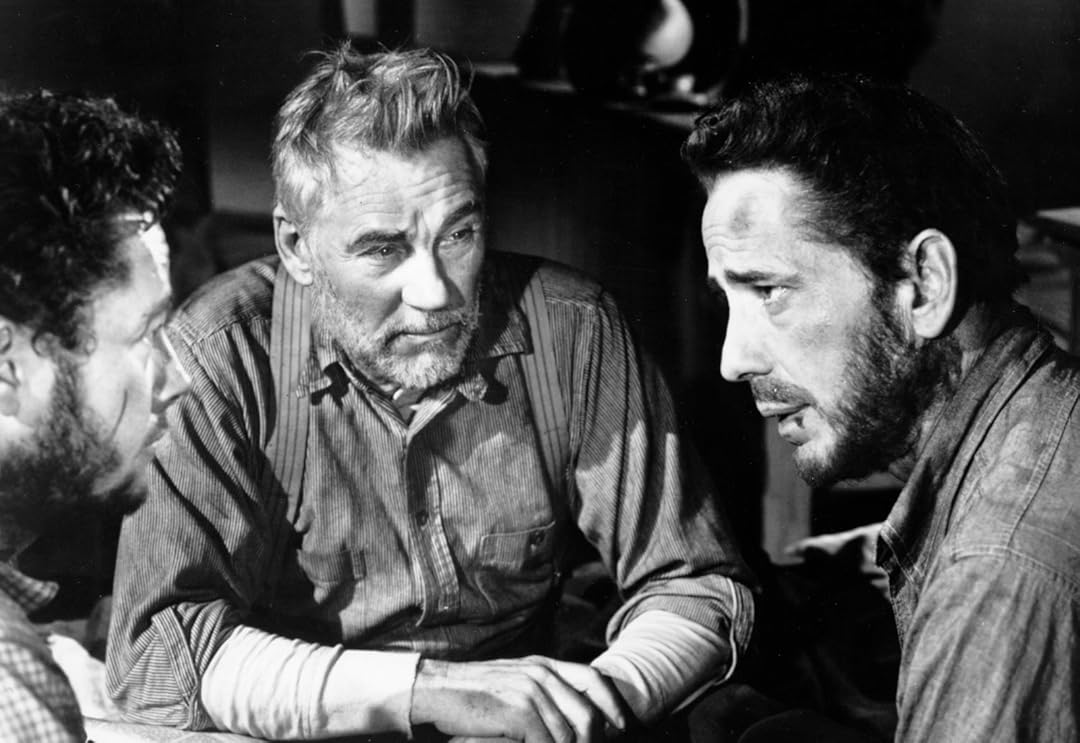

When I look at these faces, they do not look the part of movie stars, but they are iconic faces like Jean Gabin or even John Wayne. They can carry the weight of drama, and yet when you look at them, it seems like they’ve already been through drama enough in life. And so when we watch them, we appreciate their struggles and every wrinkle and whisker on their face. Because it’s these things that put them on our level as an audience. They are our fellow human beings.

If the legend holds, I can’t understand how Daryl Zanuck wouldn’t let John Ford remake Le Grand Illusion for fear he would ruin it, and then Zanuck turned right around and meddled in Renoir’s picture. It’s something I would like to learn more about, although it’s possible only the unspoken annals of history can tell us now.

What we have as a mud-caked monument is Swamp Water: A vastly interesting curio imbued with the fractured imprint of Jean Renoir. It proves you don’t have to be born in America to tell a profoundly American story. I’m not surprised Renoir was a naturalized citizen by 1946. If his cinema is any indication, we would gladly consider him one of our brethren because movies know no bounds.

4/5 Stars

Though the image quality of the print I saw hardly stands the test of time, there’s something almost modern about The Virginian’s characterizations or at least what it deems interesting to show.

Though the image quality of the print I saw hardly stands the test of time, there’s something almost modern about The Virginian’s characterizations or at least what it deems interesting to show.

“My father thanks you, My Mother Thanks you, My Sister Thanks you, and I Thank you.” – James Cagney as George M. Cohan

“My father thanks you, My Mother Thanks you, My Sister Thanks you, and I Thank you.” – James Cagney as George M. Cohan