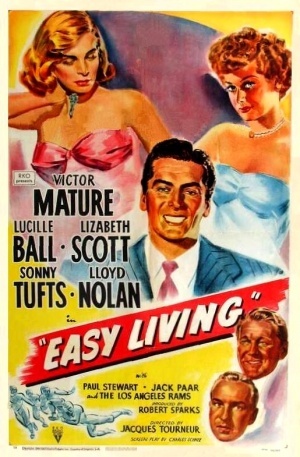

Movies like Easy Living would eventually go extinct with the advent and further proliferation of television. Now these kinds of programs would exist on cable or maybe streamers. It’s 1 hour and 17 minutes with solid stars, fairly impressive production values, and yet it’s certainly filling a niche opposite big-budget fare.

Movies like Easy Living would eventually go extinct with the advent and further proliferation of television. Now these kinds of programs would exist on cable or maybe streamers. It’s 1 hour and 17 minutes with solid stars, fairly impressive production values, and yet it’s certainly filling a niche opposite big-budget fare.

There’s an agreeable nostalgia to watching the dying breed of programmer. It opens and feels a bit like a Leave It to Beaver episode. Pete Wilson (Victor Mature) invites himself over to the home of his friend Tim McCarr (Sonny Tufts) and his good-natured wife Penny (Jeff Donnell). Their place in the story isn’t too prominent, but they give us two things. We see their domestic bliss in contrast to what Pete has, and their friendship primes us to like him.

Because Pete is a star quarterback for the Chiefs football team. Tim is one of his teammates, and they have a shared camaraderie through their profession. There’s also a time capsule aspect of professional football as we enter Hollywood’s version of a locker room from a very particular era.

The salaries are lower, the equipment looks archaic, and there’s only one Black player on the team. Some viewers might be surprised by his inclusion, and it deserves some acknowledgment. “Benny,” who we see getting treatment, is portrayed by none other than Kenny Washington. He not only played alongside Jackie Robinson at UCLA, but he and future actor Woody Strode would become the first men to integrate professional football in Los Angeles (even before Jackie broke the baseball color barrier in 1947).

If I get my dates right, he had already retired in 1949, but his presence comes with a wealth of important context. It’s also a bit more gratifying seeing him catching passes in the scrimmage than watching, say, Althea Gibson in The Horse Soldiers or Satchel Paige in The Wonderful Country. He gets to show off his excellence.

Milling about the locker room, there’s the unmistakable voice of Dick Erdman as equipment hand Buddy. Paul Stewart and Jack Paar make appearances, and the always reliable Lloyd Nolan is the team’s head coach. Anne (Lucille Ball) is a woman in the front office who’s pragmatic and signs the checks — it does feel like a kind of precursor for her work as Desilu studio head. I

t’s almost unnecessary to say she puts on the role seamlessly, though Hollywood had yet to recognize the breadth of her gifts. It would take radio and then television for the American public to realize she was one of the nation’s finest comediennes.

Thinking about it, Easy Living is one of the only films I know documenting this time in sports culture. You always hear anecdotal stories of ball players being bank tellers or car salesmen during the off-season to pay the bills before the days of gargantuan contracts. Here is a film about this kind of life. It’s a hard life for those who don’t have the market value and stability of Pete, and the team’s in a scrap for the playoffs.

Even the most casual viewer might be confused to see the squad practicing with horns on their helmets — as this was the actual Rams squad — though all the exterior and other scoreboards label the team as the Chiefs. For sports fans, it’s almost bizarre. You would think a script coordinator would care about some semblance of authentic continuity.

As much as I’m fond of Jacques Tourneur as a craftsman, you can imagine the milieu is far away from what the Frenchman was comfortable with or even mildly interested in. He’s out of his depth, though it is at its best when he is creating this assumed reality around Mature’s character.

From everything we gather about him, Pete’s in the driver’s seat. He has a gorgeous wife (Lizabeth Scott) who’s ventured out with her own design business, Liza Inc. Scott did well in some smoky femme fatale roles. Somehow, it seems like the film could have conceded to both her and Tourneur’s best impulses by taking on a more fatalistic approach.

As it stands, the drama feels a bit tedious as Mature receives a dire diagnosis about his health, presented to him by Jim Bachus, no less. The next step is figuring out how to forge ahead in football and love before life catches up with him. It’s ultimately the characters and relationships around him that feel the most worthwhile, from the hesitant love of Ball’s character to his friendships with the McCarrs, or even teammates who are given the chopping block.

In fact, all roads seem to be suggesting Ball is better and more understanding of Pete than his wife. Indiscretions aside, you can see the film putting them together, and yet the ending itself feels tacked on. What’s more, it’s disconcerting to watch our hero take back his wife with a few good, hard smacks. It’s a tenuous foundation to build a marriage on.

Since the film never quite feels like out-and-out noir, it would have been intriguing to dig into that darkness a bit more, especially if it was to seal the final act with a more cynical ending. Boxing is a lot easier to twist into a crime picture — we have so many prime examples — but I couldn’t help thinking what Easy Living could be if Tourneur was able to fashion it into something more morose and cynical like The Set-Up.

One last nitpick. Even with the inclusion of a rendition of the song “Easy Living,” it still barely makes up for giving the movie such an innocuous title. Perhaps it goes to show Jean Arthur with a fur coat is greater than Victor Mature with a football. Preston Sturges’ singular writing might have something to do with it, too.

3/5 Stars