There’s not a more fitting place to start a horror film set in England than with Stonehenge, those relics of old that we can easily imagine being hexed with pagan cults and rituals summoning some unknown evil into the world.

Jacques Tourneur is no stranger to horror films and Night of the Demon (or Curse of the Demon in the U.S.) has its most obvious roots in his work at RKO with Val Lewton and the traditions hearkening back to the days of Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie. It’s stellar company to keep indeed. What hasn’t changed is filmmaking that surpasses its budget to create something genuinely unsettling through the generation of eerie atmospherics.

Except, one could contend that this production was much more tumultuous thanks to the ongoing struggles between producer Hal E. Chester on one side and Tourneur and screenwriter Charles Bennett on the other. In their estimation, the man supplying them with funds, was compromising the integrity of their vision and what they saw in the script.

One particular point of disagreement was in the actual incarnation of the devilish spirits, which take on an actual form rather than simply being implied or left fully to the imagination. The creation of a windstorm conjured up on the spot was another instigator as Tourneur demanded the use of airplane engines instead of electric fans. It got so bad lead actor Dana Andrews even threatened to quit if there was further interference with his director’s work.

Even in spite of these forms of strife going on behind the scenes, the picture genuinely comes off as a harrowing tale imbued with the ongoing terrors of witch cults and devil worship.

The beauty is when these seemingly supernatural, spiritual, or otherwise questioned forces impart themselves on the real world. The real world is grounded by a skeptical psychologist named Dr. John Holden (Dana Andrews) who is not about to believe in any of that kind of rubbish until he has no choice but to.

You couldn’t have a better and plainly a more blatantly obvious form of opening exposition. A man sleeps on a plane. It’s Dana Andrews and the paper propped over his eyes conveniently shows his picture and bears the headline that a prominent psychologist is about to arrive in England. Behind him, keeping him up needlessly, is Joanna Harrington (Peggy Cummins), a kindergarten teacher. They don’t know it yet but they will be seeing a great deal of each other in the near future.

Certainly people note that Andrew’s career took a tailspin in the 50s due in part to bouts of alcoholism and a changing milieu but if The City Never Sleeps and Night and The Devil are representative of his low budget efforts, then I can’t say I’m too heartbroken. At least his later career gave us a few quality films to relish. At any rate, it still looks like much the same man from Laura (1944) and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). He’s simply seen more of the world.

Likewise, Peggy Cummins is a winsome heroine and a terribly underrated actress who proves a fine companion for the good doctor. They realize they have both arrived in England much for the same reason, to pay their respects to the late Professor Harrington, who died under mysterious circumstances.

Joanna (Cummins) was his niece and intuition tells her something is gravely wrong with her uncle’s untimely death. Though John is forever the skeptic, he’s nevertheless interested in investigating the research his late mentor was doing, which involved runic symbolism as well as the deceased man’s main rival Dr. Julian Karswell (Nial MacGinnis).

Taken at face value, Karswell seems a deceptively bubbly chap who fancies being a magician for the local kiddies. There’s an eccentric and ultimately ominous charisma about him, first claiming he conjured up a wind storm and then when he feels slighted, proclaiming John will be dead in three days’ time.

At first, John takes it lightly but strange occurrences that follow involving a parchment paper seem to suggest he is indeed a marked man with an impending threat on his life. If he’s not totally afraid yet then Joanne is certainly worried for him. She talks him into attending a seance with the medium of Karswell’s peculiar mother, bringing even more strange revelations to the table.

The doctor and his colleagues look to use hypnosis on a local named Hobart, caught in a catatonic state of immobility, to try and pry out answers about this foreboding ordeal right in their midst. The doctor even rushes to an outgoing train because he knows who he will find aboard; his last chance to make it out alive.

Ultimately over strong objections, Hal E. Chester won out and got images of the demon inserted into the film. I would wager it compromises the picture but it cannot completely detract from its unnerving nature, weaving together reality and mysticism into a compelling tale of irrefutable doom. There’s a shroud of powerlessness and dread overtaking the frames even as there’s a general sense our heroes are facing something they cannot quite comprehend. That works very much to its favor.

You do get the sense that Chester only saw this project as a fledgling picture to slide easily on a double horror bill. Tourneur, being the genre wizard that he was, knew he could do far more. Night of the Demon, like the finest horror films in the tradition, remains with us, lingering even after the credits have rolled.

4/5 Stars

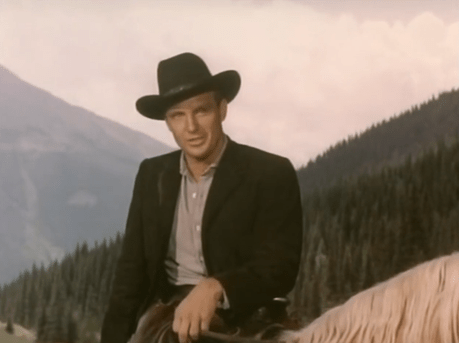

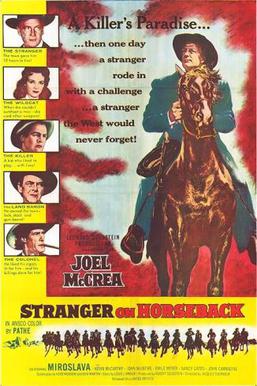

I didn’t know my Grandpa too well because he passed away when I was fairly young but I always remembered hearing that he really enjoyed reading Louis L’Amour. It’s not much but a telling statement nonetheless. I’ve read and seen Hondo (1953), which stars John Wayne and Geraldine Fitzgerald, and yet I’d readily proclaim Stranger on Horseback the finest movie adaptation of an L’Amour novel.

I didn’t know my Grandpa too well because he passed away when I was fairly young but I always remembered hearing that he really enjoyed reading Louis L’Amour. It’s not much but a telling statement nonetheless. I’ve read and seen Hondo (1953), which stars John Wayne and Geraldine Fitzgerald, and yet I’d readily proclaim Stranger on Horseback the finest movie adaptation of an L’Amour novel.