Claire’s Knee is a film made for color. Eric Rohmer’s other films up to this point had almost exclusively been black and white, but it’s as if he knew that his newest oeuvre deserved different treatment. It’s vast countrysides and glistening lakes abundant with flowers and fruits fill up our senses. We get to watch and see and experience the beauties of this oasis. And there is no music because the songs of the birds suffice.

Claire’s Knee is a film made for color. Eric Rohmer’s other films up to this point had almost exclusively been black and white, but it’s as if he knew that his newest oeuvre deserved different treatment. It’s vast countrysides and glistening lakes abundant with flowers and fruits fill up our senses. We get to watch and see and experience the beauties of this oasis. And there is no music because the songs of the birds suffice.

Jerome (Jean-Claude Brialy) is a reserved but genial diplomat, who also pulls off his beard quite well. He’s taking a peaceful holiday at Lake Annecy as he prepares himself for marriage with his longtime sweetheart. Quite by chance, he bumps into an old friend named Aurora during a jaunt in his speedboat. Through her, he meets her landlady Madame Walter, the lady’s daughter Laura, and finally Claire, Laura’s older half-sister. It’s an increasingly interesting chain of acquaintances.

The course of the film follows the progression of the summer days signified by white inter-titles expressing the date and time. During these days Jerome, in a sense, willingly becomes Aurora’s “Guinea pig” for her next novel as they discuss love, life, relationships, desire, and the like. Early on, Aurora notices that young Laura has taken some liking in Jerome, and he good-naturedly pursues the relationship, to see what happens.

She’s a young girl who has some big ideas. Laura admits feelings for Jerome, but it’s seemingly only fleeting young love. She still has many years ahead of her, and yet her opinions on love and friendship are already forged. She’s willing to discuss them in depth with her much older counterpart. They take a hike through the mountains together, dance together on Bastille Day, but it’s not a romance. She moves on to a younger boy more fitting for her.

She’s a young girl who has some big ideas. Laura admits feelings for Jerome, but it’s seemingly only fleeting young love. She still has many years ahead of her, and yet her opinions on love and friendship are already forged. She’s willing to discuss them in depth with her much older counterpart. They take a hike through the mountains together, dance together on Bastille Day, but it’s not a romance. She moves on to a younger boy more fitting for her.

But that’s enough skirting around the uncomfortable. It’s the entrance of Claire that feels integral to the film, if not simply for the fact that the film’s title revolves around her. The fact is Claire is a beautiful girl, who intrigues and disturbs Jerome for the simple fact that her physical appearance is all he knows about her.

The moment he witnesses her picking fruit off a tree up above him, he cannot stop looking. He’s absolute powerless around her. She intimidates and casts a spell that mystifies him. The fact he wishes to touch her knee is hardly a thing to be taken all that seriously. By this point, we know that Jerome and Aurora are not all that serious. It’s almost as if they’re playing a game. And yet Jerome still earnestly wishes to touch Claire’s Knee.

In a moment of sincerity he even acknowledges he is drawn to thin delicate girls, but having a girl made to order would hardly be a recipe for true love. Because the fantasy could never equate to actual compatibility and joy for two individuals. The perfect moment does finally arrive, and it seems like Jerome can finally act out on his desire. He is caught in the rain with Claire and they must wait, taking refuge from the rain. He has news about her boyfriend that brings her to tears. In an instant, he caresses her knee, but soon enough all the desire is gone and it gives way to a good deed.

Thus, somehow Jerome maintains his good-natured personality despite his potentially disastrous relationships with the two girls. It’s as if he knows that inconsequential flings and fantasies can never measure up to true love. He heads off ready to marry his bride to be. We never get a feeling that this is some odd ploy to get a dramatic rise out of its audience. Rohmer’s moral tale is genuinely curious about love. In truth, it’s packed full of musings and revelations on the issue. It draws the conclusion that love means nothing without action.

Thus, somehow Jerome maintains his good-natured personality despite his potentially disastrous relationships with the two girls. It’s as if he knows that inconsequential flings and fantasies can never measure up to true love. He heads off ready to marry his bride to be. We never get a feeling that this is some odd ploy to get a dramatic rise out of its audience. Rohmer’s moral tale is genuinely curious about love. In truth, it’s packed full of musings and revelations on the issue. It draws the conclusion that love means nothing without action.

To his credit, Brialy pulls off the role nearly flawlessly, because he could have so easily seemed like a perverted jerk, but somehow he still comes out of this film with his reputation intact. Perhaps it’s because Laura and Claire are such striking characters. Jerome somehow pales in comparison, despite his age. Although young, Laura seems beyond her years and then there’s Claire. A young woman so exquisitely beautiful in a natural, carefree sort of way. She is perfect to be the subject of this film.

4/5 Stars

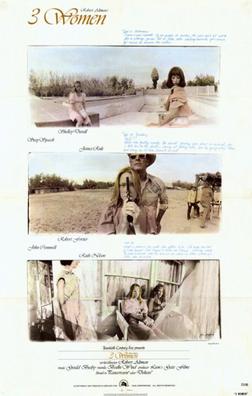

Supposedly Robert Altman’s inspiration for 3 Women came from a dream he had, as with many of the most original ideas out there. Admittedly, in some ways, the resulting project feels like his rendition of a European art-film. It has some roots in Bergman and Polanski while transposing the action to his usual locales that are inbred into the fabric of America — places like the California deserts and Texas.

Supposedly Robert Altman’s inspiration for 3 Women came from a dream he had, as with many of the most original ideas out there. Admittedly, in some ways, the resulting project feels like his rendition of a European art-film. It has some roots in Bergman and Polanski while transposing the action to his usual locales that are inbred into the fabric of America — places like the California deserts and Texas.

“If you had a choice would you either love a girl or have her love you?”

“If you had a choice would you either love a girl or have her love you?”