Kudos must be extended to Richard Linklater for actually being proactive and going out to shoot the movie countless of us have doubtlessly tossed around in our mind’s eye. Taking our town — the places we know intimately — and building a portmanteau out of it with a group of friends.

Kudos must be extended to Richard Linklater for actually being proactive and going out to shoot the movie countless of us have doubtlessly tossed around in our mind’s eye. Taking our town — the places we know intimately — and building a portmanteau out of it with a group of friends.

There’s nothing flashy or that original about this universal concept per se, but it always strikes one as more than just a straightforward story. There is a bit of artistry to its execution, while still functioning on the most shoestring of budgets.

Even one of my favorite bands in high school, Reliant K made their own rendition involving a soccer ball. But again, Linklater has time and history on his side, because he was the one who actually got it made. Few others would have the wherewithal to get it off the drawing board.

What’s more, Slacker actually has some genuine life to it by capturing a very specific subculture and locale like a time capsule of 1990s Austin, Texas. It takes pieces of the world he knows and promotes them to a wider audience, which is one of the cool perks of cinema. It’s able to take a localized image and globalize it, despite how humble the reach might have been, to begin with.

Better yet, the up-and-coming director dares to open the picture with his own monologue, musing about his dreams and alternate realities to his uninterested taxi driver. He teases a hypothetical scenario where he was invited into a beautiful girl’s hotel room just for standing at the bus stop. He matter-of-factly curses to himself that he should have stayed behind, before picking up his bags to go, effectively choosing a different fate.

From thenceforward, the camera is on the move as well. Because this isolated sequence is only one among a whole bunch of other asides helping to predict the conversing integral to The Before Trilogy or even a more communal vision like Dazed and Confused. Though the characters nor the dialogue builds that same type of rapport with the audience, one could easily argue they are not supposed to.

This is a near stream-of-consciousness exercise with the camera following its whims, roving around, and taking an almost bipolar interest in everything. You get the sense Linklater knew full-well what he wanted to capture; still, he makes it look organic. There’s this constant mixture of intellectualization and socializing going on.

A mother is run over by a car. A husker sings his tune on a street corner. People run into each other serendipitously. Handheld walk-and-talk scenarios make the action simple and fast.

Some of the characters are definitely “whack,” but that’s all part of the fun. The dialogue grabs hold of any weird quirk or a bit of oddness it can from conspiracy theories, aliens, television, the JFK assassination, anarchy, literally anything at all.

This one is an important landmark of indie filmmaking right up there with Cassavetes works or Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989), paving the way for everything from Clerks to the wave of indies that came to fruition in the mid-90s and early 2000s.

While I don’t find it quite compelling in this given era, there’s no way to underplay what it means for movies. Many are indebted to Linklater, and the beauty is that the director is still churning out quality work, both personal and commercial.

In fact, I’m a little in awe of him, because it seems like he’s constantly managing to make the projects he wants. He will not give up on his own artistic aspirations. In the age of the blockbuster, those are admirable motivations.

3/5 Stars

I’ve been of the certain age where it seems like every friend you have is getting married in the next year. It’s an exhilarating time albeit expensive and a bit taxing (if you’re even able to go to all of them). But most of us wouldn’t trade the joy of being a part of these experiences for anything.

I’ve been of the certain age where it seems like every friend you have is getting married in the next year. It’s an exhilarating time albeit expensive and a bit taxing (if you’re even able to go to all of them). But most of us wouldn’t trade the joy of being a part of these experiences for anything.

Upon watching A Few Good Men for the first time, it was hard not to draw parallels with An Officer and a Gentlemen for some reason and it went beyond some cursory elements such as both films involving branches of the military. Perhaps more so than that is the intensity that manages to surge through the plot despite the potentially stagnant battleground like Cadet Schools, Courtrooms, and the like. And that can in both cases is a testament to the stellar performances in front of the camera.

Upon watching A Few Good Men for the first time, it was hard not to draw parallels with An Officer and a Gentlemen for some reason and it went beyond some cursory elements such as both films involving branches of the military. Perhaps more so than that is the intensity that manages to surge through the plot despite the potentially stagnant battleground like Cadet Schools, Courtrooms, and the like. And that can in both cases is a testament to the stellar performances in front of the camera. Themla & Louise hardly feels like typical Ridley Scott fare but then again, neither is this a typical movie. It pulls from numerous genres that have been depicted countless times before from buddy movies to caper comedies, road films, and the like. But perhaps the intrigue begins with the two leads.

Themla & Louise hardly feels like typical Ridley Scott fare but then again, neither is this a typical movie. It pulls from numerous genres that have been depicted countless times before from buddy movies to caper comedies, road films, and the like. But perhaps the intrigue begins with the two leads. There’s something remarkably moving about the beginning of Saving Private Ryan. I’ve only felt it a few times in my own lifetime whether it was family members recognizing names on the Vietnam Memorial tears in their eyes or walking over the sunken remains of the U.S.S. Arizona at Pearl Harbor. It’s these types of memories that don’t leave us — even as outsiders — people who cannot understand these historical moments firsthand.

There’s something remarkably moving about the beginning of Saving Private Ryan. I’ve only felt it a few times in my own lifetime whether it was family members recognizing names on the Vietnam Memorial tears in their eyes or walking over the sunken remains of the U.S.S. Arizona at Pearl Harbor. It’s these types of memories that don’t leave us — even as outsiders — people who cannot understand these historical moments firsthand. I’ve heard people like director Jean-Pierre Gorin say that there is little to no distinction between documentary and fiction. At first, it strikes us as a curiously false statement. But after giving it a moment of thought it actually makes sense, because no matter the intention behind it, the medium of film is always subjective. It’s always a created reality that’s inherently false and even in its attempts at realism — that realism is still constructed.

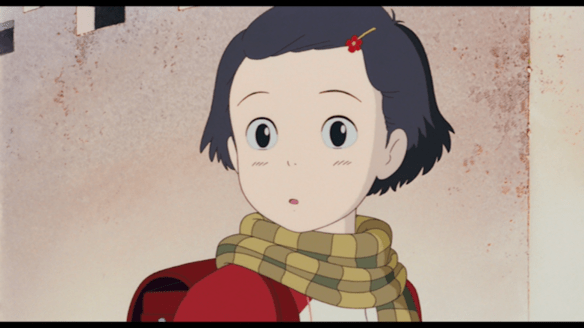

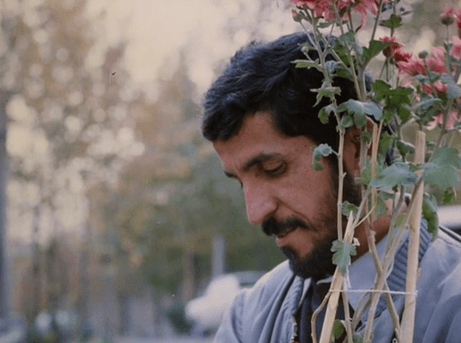

I’ve heard people like director Jean-Pierre Gorin say that there is little to no distinction between documentary and fiction. At first, it strikes us as a curiously false statement. But after giving it a moment of thought it actually makes sense, because no matter the intention behind it, the medium of film is always subjective. It’s always a created reality that’s inherently false and even in its attempts at realism — that realism is still constructed. The beauty of Close-Up that not only does it feature the real individuals involved in this whole ordeal: There’s Sabzian playing himself, the Ahankhah family who brought the case to court, and Kiarostami appearing as well. But it blends the actual footage from the trial with reenacted scenes set up by the director as if they are happening for the first time.

The beauty of Close-Up that not only does it feature the real individuals involved in this whole ordeal: There’s Sabzian playing himself, the Ahankhah family who brought the case to court, and Kiarostami appearing as well. But it blends the actual footage from the trial with reenacted scenes set up by the director as if they are happening for the first time. The opening notes of Joan Jett hollering “Bad Reputation” made me grow wistfully nostalgic for Freaks & Geeks reruns. The hope budded that maybe 10 Things I Hate About You would be the same tour de force narrative brimming with the same type of candor. It is not. Not at all. But that’s okay. It has its own amount of charms that forgive the obvious chinks in the armor of this very loose adaptation.

The opening notes of Joan Jett hollering “Bad Reputation” made me grow wistfully nostalgic for Freaks & Geeks reruns. The hope budded that maybe 10 Things I Hate About You would be the same tour de force narrative brimming with the same type of candor. It is not. Not at all. But that’s okay. It has its own amount of charms that forgive the obvious chinks in the armor of this very loose adaptation. This was not the film I expected from the outset, and oftentimes that’s a far more gratifying experience. Nostalgia was expected and this film certainly has it, even to the point of casting the legendary funny man and cultural icon Don Knotts in the integral role as the television repairman.

This was not the film I expected from the outset, and oftentimes that’s a far more gratifying experience. Nostalgia was expected and this film certainly has it, even to the point of casting the legendary funny man and cultural icon Don Knotts in the integral role as the television repairman. Yogi Berra famously once said, If the world was perfect, it wouldn’t be. And to go even further still, in As You Like It Shakespeare wrote, the world is a stage and all the men and women are merely players. They have their exits and entrances.” So it goes with this film — The Truman Show. In fact, in some ways, it feels reminiscent of the likes Groundhog Day and even Jim Carrey’s later project

Yogi Berra famously once said, If the world was perfect, it wouldn’t be. And to go even further still, in As You Like It Shakespeare wrote, the world is a stage and all the men and women are merely players. They have their exits and entrances.” So it goes with this film — The Truman Show. In fact, in some ways, it feels reminiscent of the likes Groundhog Day and even Jim Carrey’s later project  However, as things progress there begin to be even more warning signs and indications to Truman that all is not right in his world. In truth, his life is a TV show, where everyone is privy to a television program including the audience, but that program ends up being his life. Truman Burbank is at the center of this orchestrated universe and he has been for 30 years. But over time he gets wise to the game and he’s looking to push the limit of the rules as far as they will go so he can get to the bottom of it all.

However, as things progress there begin to be even more warning signs and indications to Truman that all is not right in his world. In truth, his life is a TV show, where everyone is privy to a television program including the audience, but that program ends up being his life. Truman Burbank is at the center of this orchestrated universe and he has been for 30 years. But over time he gets wise to the game and he’s looking to push the limit of the rules as far as they will go so he can get to the bottom of it all.  If there is a Creator of the Universe, our universe, The Truman Show puts it in a clearer light. Christoph seems like a somewhat selfish individual who allows his creation to walk off set rather reluctantly, but he finally does let go. Thus, his actions seem to make it clear that the most loving Creator possible would let his creation do what they pleased. He would be in control, but he would willingly give his created ones free will to do what they want. That makes sense to me. I would want to be a living, breathing, mistake-doing individual rather than a mechanized robot. That’s the beauty of this life.

If there is a Creator of the Universe, our universe, The Truman Show puts it in a clearer light. Christoph seems like a somewhat selfish individual who allows his creation to walk off set rather reluctantly, but he finally does let go. Thus, his actions seem to make it clear that the most loving Creator possible would let his creation do what they pleased. He would be in control, but he would willingly give his created ones free will to do what they want. That makes sense to me. I would want to be a living, breathing, mistake-doing individual rather than a mechanized robot. That’s the beauty of this life.