“Like a rat, I want to be beautiful. Because you have a beauty that can’t be reflected in pictures” -sung by Linda, Linda, Linda

During the grainy opening scene of Linda, Linda, Linda there’s some time spent figuring out how these characters relate to our story as two AV nerds look to video a high school girl who is introducing a school’s forthcoming cultural festival.

It’s not so important to get to know who they are as to realize they will become the bookend for the movie and the parameters of its world. Because when you are a Japanese student, “Bunkasai” really is your chance to shine in front of your peers.

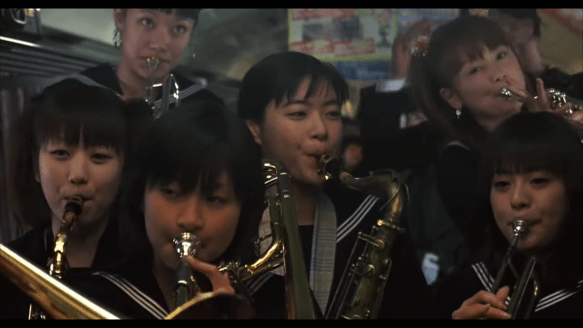

Linda, Linda, Linda captures this environment better than any other film I’ve seen thus far, and it’s because there’s really an ecosystem built out. Each class has their own task, game, or food vendor that they’re preparing for. Sports teams will have exhibitions. Clubs will have booths. Bands put on performances on the big stage for everyone.

However, this canvas wouldn’t work without the human drama we come to expect with high school. One girl hurts her hand and petty disagreements lead to the dissolution of an all-girl rock band. Three of its members, Kei, Kyoko, and Nozomi, decide to form a new quartet without their lead singer. Son (Bae Doona), the unblinking Korean exchange student is quickly found as her replacement.

Some western audiences might not recognize what an odd choice Son is to be their lead singer. Japanese is not her first language. They often have trouble communicating with her (A stunted bus stop interaction brought back all sorts of personal memories from my time overseas). She has to learn all the lyrics to their setlist and she’s a bit kooky. Still, it fosters a beautiful kind of relationship.

There’s something leisurely and unhurried about the pacing of the movie. Characters are put in front of us, and yet we don’t feel like there’s some objective to be obtained. It’s about getting to know them and observing their situations.

My primary avenue to consider this film is through the filter of my own experience. I went to a cultural festival like this. There was giant Jenga and classrooms turned into rollercoasters and carnival games. We had boba, sweet potatoes, and frankfurters (while supplies last). But the best part was the music. I saw many of my students come into their own, witnessing sides of them you never see in the classroom. Raging fuzz-filled guitar solos, singers coming out of their shells, and girl guitar gods rocking out.

In fact, I was up on that stage too. Rather like Son I was an outsider. I got asked to sing a song in English and so without any musical training or a voice to speak of I agreed spending several weeks learning a One Direction tune. It’s not quite The Blue Hearts, but I’m not much of a singer. Son spends her time training at a karaoke drink bar.

If that experience was hardly a highlight of my life, I fall back on the experiences I got to witness. Linda Linda Linda has that same raucous joie de vivre we rarely attribute to Japanese culture. That’s what made it so joyous watching my students rock out to One OK Rock and Green Day.

It’s the same energy making Linda, Linda, Linda buzz with a pervasive joy. The audience imbibes the energy, cheers it on, and the musicians feed off of it. Nerves die away. They give themselves over to the music and enjoy themselves. If it’s like my school, these kids will probably never be professional musicians, but that’s hardly the point. Music has joys going beyond fame and monetary gain.

I was once taken by the idea of James Carse with his infinite games. Finite games have winners and losers. In infinite games, the players seem to be cooperative feeding into something bigger than themselves and utilizing a different, intrinsic rubric for success.

Although Linda…deviates mostly from the similar-sounding Swing Girls, what they share beyond a frantic slap-dash finale, is this performative exhilaration found most often in music. Soon enough, the festival is over and that’s the end of it.

But for a couple shining moments in the middle of the setlist, they were at the center of something spectacular. It’s easy to be a sucker for these kinds of stories when they feel so closely tied to my own fond memories. Long live Linda, Linda, Linda.

4/5 Stars

One could choose any number of labels to attempt categorizing Departures. It’s a film indebted to the rapturous compositions of the past. It shares elements akin to any police procedural ever made or for that matter, the veterinary antics from a British gem like All Creatures Great and Small.

One could choose any number of labels to attempt categorizing Departures. It’s a film indebted to the rapturous compositions of the past. It shares elements akin to any police procedural ever made or for that matter, the veterinary antics from a British gem like All Creatures Great and Small.