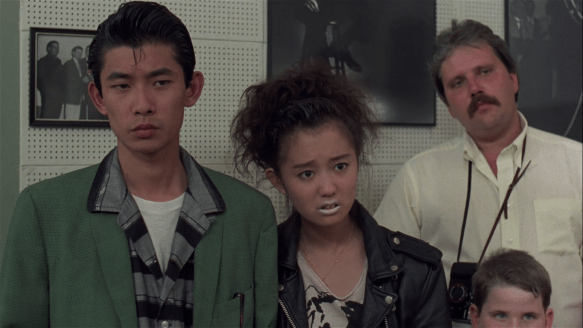

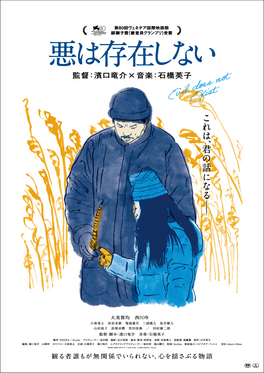

From watching one of director Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s interviews, it’s made clear he started Evil Does Not Exist by using the music of Eiko Ishibashi as inspiration. There’s a swelling breadth to it augmenting everything it touches. At times doleful and then evolving into a plinking intensity looking for release.

From watching one of director Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s interviews, it’s made clear he started Evil Does Not Exist by using the music of Eiko Ishibashi as inspiration. There’s a swelling breadth to it augmenting everything it touches. At times doleful and then evolving into a plinking intensity looking for release.

It plays against a backdrop of austere forests, trickling streams, and fresh dustings of snow outside the prying eyes of the Tokyo metropolis. The score becomes a viable metaphor for the movie itself.

The film’s relationship with its characters is also distinct. There’s something Bressonian about it. Because the famed French director famously envisioned his actors as models and often cast non-professionals. He wasn’t looking for performances in the conventional sense.

I don’t know Hamaguchi’s filmography all that well, but it doesn’t feel like he has a stock company. Rather he likes to use different actors for what they offer in each distinct context. We spend the opening minutes watching this man named Takumi (crew member Hitoshi Omika) exist and act, though not in the way we normally think of it in film.

It is slow cinema in the sense that we watch him in the paces of his life from collecting stream water to chopping wood. This tells us more about him than any amount of dialogue might, but it also signals to us what kind of movie we’re in for.

Hamaguchi is prepared to steady your heart rate, and I could use much more of this amid the daily grind. However, it is a tightrope because it’s so easy to lose your audience as they grow potentially disillusioned by the pacing and elongated editing schemes. Seeing as Drive My Car was over 3 hours and Happy Hour over 5 hours, there’s something about Evil Does Not Exist that feels, if not economical, at least more contained.

Takumi’s relationship with his quizzical daughter is rather reminiscent of Leave No Trace (2018). So much of their affection and relationship is facilitated through their shared love of nature with the father passing down his knowledge to his girl.

The movie’s dramatic conflict comes with an impending land development. A Tokyo-based talent agency has plans to install a Glamping site, which ostensibly is little more than a ploy to get a coveted tax subsidy.

Like any conscientious Japanese company, they do their due diligence by holding an open forum for the locals to voice their concerns. The subsequent extended community scene is trademark Hamaguchi with a sprawling dialogue exchange. While it’s not a Park and Rec episode, maybe it’s the Japanese alternative.

There’s something tight-knit about this small community rubbing up against the wary encroachment of the Tokyo firm. Their concerns are well-founded and measured. They see through everything with a clarity that no formal Japanese double-speak can totally obfuscate.

Their opposition, if you will, are the archetypes of a veteran salaryman and his deferential associate who hasn’t quite detached from her empathy. The audience I sat with was mostly quiet if attentive, but there was more than one occasion I found myself chuckling to myself, either from a line of Japanese dialogue or an interaction.

I found this section of the movie especially rich with behavioral humor. There’s a youthful rebel in baggy pants who tramples over the typical decorum and has to be held back. The ritualistic bowing is met with contempt and even Takumi is brusque. They want to try to recruit him as an advisor for their glamping endeavor. He has no business card to give them as is customary, nor does he want their token gifts or pleasantries.

These might be subtle, but it’s a pleasure to watch how these locals eschew what feels like traditional norms. Because so much of Japanese life feels like a tug of war between exterior and interior identity. We say don’t judge a book by its cover and here it holds true on more than one occasion. Many of these characters seem perceptive and ultimately nuanced.

One of the other surprises is how Hamaguchi turns the “enemy” into real people over an extended car ride back to the countryside. They know they’re not dealing with idiots, but their superior encourages them to return and ensure they stay on schedule. It feels like an untenable mission. Having seen both sides, we feel for them. Their hearts aren’t in it.

They trade their hopes, aspirations, and dating prospects in a way that you rarely see in Japanese work culture without alcohol as a social lubricant. Despite the modest scope, I’m not sure if others are aware of how radical this feels.

Takumi takes his guests out into the natural world and allows them to walk alongside him in his daily tasks. Later that same evening his daughter disappears and darkness is closing in. There’s something dismal and inevitable about it as the entire population mobilizes to try and find her.

Without drawing it out too much, they do discover the girl as well as a fawn and doe who feel like semiotic creatures. It’s no coincidence there was a movie called The Deer Hunter. He lives on the fringes of the frame here with his bullets flying in a game of offscreen roulette.

The willfully oblique ending is inexplicable, but I could not look away. You can take it one of two ways: either with mystified displeasure or a contentment in not understanding everything. I fit in the latter category. It was like staring at a mesmerizing spell.

Somehow it feels like a pleasure and a privilege to get these moments in time slowed down for us — sequences that are purposefully meditative. I couldn’t help thinking how much of a backward society we live in that it takes a screen in the dark projecting images in front of us to draw a person out of the hubbub and back into nature. Are we so removed that moving pictures are one of the last vestiges of the natural world in the urban jungle? Because it’s not the real thing.

I would find it instructive for the director to expound on his themes at length — that’s what I want — and yet the movie leaves the results up to us. Still, if nothing else, Hamaguchi gives us a reminder of our imperative ties to the natural world lest we forget where we originate. As much as we try, life cannot always be domesticated comfort. There’s wild beauty out there we would do well to remember.

I think we share an appreciation of the natural world. Maybe it’s semantics or a mere positive affirmation, but if evil does not exist, we could also conjecture, like The Deer Hunter, that interpersonal discord, war, and death are natural in a chaotic world.

However, I would not say that humans nor beasts are inherently good. For the time being, we live in a broken, fallen world and this is just a reality. Our world is full of entropy, but this is not meant to be our resting state.

It’s all the more reason to do our utmost to look after our environments, be kind to our neighbors, and work toward human flourishing. Of course, that’s easier said than done, but like Thomas Aquinas posited I would like to believe that good can exist even without evil. We’re not there yet, but I’m still hopeful.

3.5/5 Stars