Run for Cover is rarely talked about in conversations of westerns, but there’s something fascinating about getting a James Cagney-led sagebrusher. Like seeing Edward G. Robinson in The Violent Men, it’s hard not to read his entire history of gangster pictures into his backstory because although it’s a different decade, genre pictures still hold a place in the viewing public’s hearts.

Before they broke out with the likes of Hud, Harriet Frank Jr. and Irving Ravetch penned the story this movie was based on. Although it hardly has the pedigree of Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar, the images of the picture are still stunning in their own right shot on location in Aztec, New Mexico.

The opening premise is frankly pretty corny. Cagney meets John Derek at a watering hole very conveniently. They ride on together with no apparent purpose except to get to the nearby town. Then, in a freak misunderstanding, while they’re shooting some scavengers out of the sky, the two men are mistaken for train robbers, and they have a bag full of cash literally dropped in their laps.

The locomotive heaps on the coal to race back to town to sound the alarm after their close scrape with the “outlaws.” Realizing what has happened, Cagney, always the level-headed one, looks to follow behind and return the money. They have nothing to hide. Still, there’s only one way this might end.

The mountains in the background are towering — truly awesome to look at — but there are more pressing matters at hand. It’s rather foreboding. It’s been some time between viewings, but there definitely are elements of The Ox-Bow Incident and Johnny Guitar here where the lynch-mob mentality takes over the local populations driven mostly by fear and traumatic experience.

However, this is all a false start, a way of developing the scenario ahead of us. It’s about that same man played by Cagney — now the town marshal — and his young companion who’s stricken with a life-altering injury. They must figure out what it means to live their lives.

Cagney rarely got a lot of late-period credit. There’s White Heat and then One, Two, Three comes to mind — these are marvelous showcases for his tenacious talents. Run for Cover is rarely talked about, whether it’s in the context of ’50s westerns, the career of Nicholas Ray, or that of Cagney himself.

But it does feel like another picture to buttress his legacy with. Not because it’s some grand masterpiece; he proves that he can make a slighter, quieter picture like this sing. Because his talents were not always purely bellicose or irascible. He has a more general charisma even later in his career.

He’s summed up so beautifully in a crucial scene. The doctor says Derek will never walk again. Cagney won’t hear of it, and he walks into the adjoining room as the boy lies on the floor crying out that he can’t get up. As their kindly Swedish benefactor (Viveca Lindfors) attends to him, Cagney simply beseeches him to “get up.”

There’s an authority in his words that feels almost Christ-like. It might seem like it comes out of a place of callousness, but really there is so much concern there. He doesn’t want the boy to give in and waste his life. In some manner, he is a miracle maker, a man of faith looking to bring the best out of this boy.

it’s a fairly slow-paced, straightforward western and this means much of the brunt of the movie must be carried by the merit of the performances — the relationships cultivated between them.

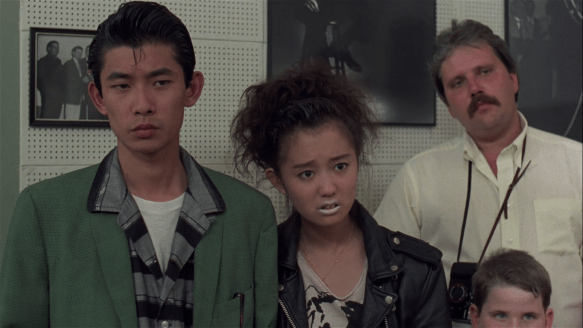

John Derek feels like little more than a pretty face, and the young actor might have said as much, but Cagney seems generous to him just as his character is generous to his young companion enlisting him as his deputy. He gives him credence and importance in this movie that he wouldn’t get otherwise without such a consummate professional to partner with.

There is some menace in the picture. Ernest Borgnine represents one — a shifty outlaw — and later some godless out-of-towners come tumbling into church mid “Christ The Lord is Risen Today” prepared to raid the bank.

What Run for Cover has to its advantage is how it turns all manner of dynamics on its head. The sheriff lambasts the townsfolk who are so righteous, so willing to condemn others, even as they are supposed to represent civilized society.

Then his one protégé becomes the film’s final and most crucial point of conflict, and this is not just like the Searchers, the ornery old man budding heads with the impetuous youth.

It’s a different kind of complication as they must face off against one another and come to terms with who they are down to their very core. There’s a clear-cut emotional intensity that can only be resolved in one telling act. It’s tragedy and redemption all rolled up into one, and here we have something that feels distinctly of Nicholas Ray.

3.5/5 Stars