NOTE: I’m never too concerned about spoilers but just be warned I’m talking about The Irishman, which will come out in November. If you want to be surprised maybe wait to read this…

NOTE: I’m never too concerned about spoilers but just be warned I’m talking about The Irishman, which will come out in November. If you want to be surprised maybe wait to read this…

The opening moments caused an almost immediate smile of recognition to come over my face. There it is. An intricate tracking shot taking us down the hallway to the tune of “In The Still of The Night.” We know this world well.

Martin Scorsese does too. Because it’s an instant tie to Goodfellas. In some sense, we are being brought back into that world. Except you might say that The Irishman picked up where the other film left off, filling up its own space, coming to terms with different themes. This is no repeat.

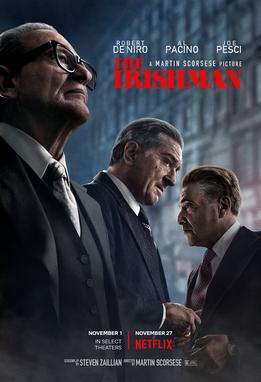

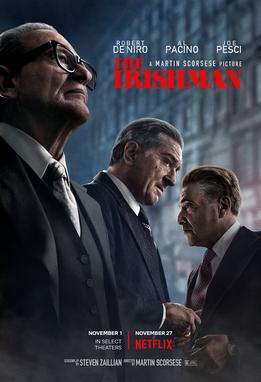

A day ago if badgered about the film I would have said it’s about a hitman named Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro) who had ties with the Buffalino crime family (Joe Pesci) and worked alongside Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino). The famed union teamster disappeared without a trace, only to become one of the most mythical unsolved cases of all time.

And yes, I had to take a few moments to get used to a de-aged Robert De Niro, although I think it might have been the blue “Irish” eyes, so I quickly accepted it and fell into the story. On a surface level, these are the initially apparent attributes. However, it’s a joy to acknowledge it’s so much more. Because all the greatest films offer something very unique unto themselves — and to their creators — in this case the world of organized crime.

We’re so used to having Scorsese and De Niro together; it’s staggering to believe their last collaboration was Casino (1995). Meanwhile, Joe Pesci came out of his near-decade of retirement to join with De Niro again and continue their own substantial screen partnership together. Some might be equally surprised to stretch their memories and realize Pacino and Scorsese have never worked together. Both have such deep ties to the American New Wave and the crime genre. The pedigree is well-deserved on all accounts.

But there’s something ranging even deeper and more elemental, resonating with us as an audience. This is not Sunday school truth but a type of hazy mythology with flawed titans going at it in a manner that feels almost bizarre. There are no pretenses here. If you are familiar with Scorsese’s work from Mean Streets to Goodfellas, this is an equally violent and profane work. And yet how is it we begin to care about characters so much that their relationships begin to carry weight? Especially over 3 and a half hours.

It is a monumental epic and that opening tracking shot I mentioned leads us to a white-haired, wheelchair-bound man who has seen so much over the course of his lifetime. Voiceover has a hallowed place in the picture akin to Goodfellas, but again, the man at the center of it all has such a different place in the story.

What’s more, The Irishman really is a full-bodied meditation on this lifestyle of organized crime. Yes, it’s placed in a historical context, but Sheeran is a man we can look at and analyze. He is a sort of case study to try and untangle the complexities of such an environment.

Steven Zaillian’s script lithely jumps all over a lifetime woven through the fabric of popular history, aided further by the music selections of Robbie Robertson (of The Band acclaim) and real-life touchstones ranging from the Bay of Pigs, the Kennedy Assassination, Nixon, and Watergate.

Thelma Schoonmaker makes the action accessible and smooth with ample artistic flourishes to grapple with the societal tensions and cold, harsh realities. Still, the majority of the picture is all about relationships. Everything else converges on them.

Sheeran didn’t know it then, but the day he met Russell Bulfino (Pesci) on his meat trucking route, would be the beginning of a beautiful friendship. Because he’s a man with clout and connections. Everyone comes to him, he expects other people to pay deference to him, and he looks kindly on those who carry out his favors.

In his company, Sheeran has a formidable ally, and he starts rising up the ranks even running in the same circles of the acclaimed Jimmy Hoffa. Being “brothers” as it were, it’s as if Sheeran and Hoffa understand one another intuitively and in a cutthroat world, they have a deep-seated, inalienable trust in one another. Who is the man Hoffa comes to have in his room to be his friend, confidant, and bodyguard if not Frank? You can’t help but get close to someone in that context.

Al Pacino just about steals the show blowing through the film with a phenomenally rich characterization of the famed teamster, because he willfully gives a tableau of charm, charisma, warmth, humor, mingled with a ruthless streak and utter obstinacy. His loyalists are many as are his enemies. It’s facile to be a mover and a shaker when you’re an immovable force of nature.

Even as Sheeran is busy, mainly on the road, his first wife and his kids (and then his second wife) are always present and yet somehow they never get much of a mention, rarely a line of dialogue, always in the periphery. This in itself is a statement about his family life.

One recalls The Godfather mentality. Where family is important but so is the family business and never the twain shall meet. Womenfolk and children are protected, shielded even, and the dichotomy is so severe it’s alarming.

In that film, the cafe moment is where Michael (a younger Pacino) makes a life-altering decision. For Frank, that mentality somehow comes easily for him. Michael was the war hero and thus stayed out of the family business for a time. Frank’s involvement in “painting houses,” as the euphemism goes, is just an obvious extension of the killing he undertook in Europe.

It’s curious how everyone mentions his military experience, the fact that he knows what it’s like, and how that somehow makes what he’s called to do second-nature. Again, it’s business. It’s following orders. If you do a good job, if you do the “right thing,” you get rewarded.

There are some many blow-ups and hits and what-have-yous, it wears on you to the point of desensitization, especially when you’re forced to laugh it off uneasily. This is very dangerous but again, it’s anti-Godfather, which was a film where these were the moments of true climax and meaning and import for the psychology of the characters. Where Michael evolves and takes over the territory. Where his older brother Sonny is killed and his other brother Fredo gets killed. There’s meaning in every one of them.

In the Irishman, it could care less. Everything of true importance seems to happen around conversations, in dialogue, between people. To a degree that is. Because dynamics are set up in such a way and the culture and the unyielding ways of men make it inevitable, opposing forces will rub up against one another.

The complicated realms of masculinity, pride, and respect make minor tiffs and bruised egos the basis of future gang wars and vendettas. Phone calls are testy and people are pulled aside to get straightened out before more serious action is taken. It’s a social hierarchy where go-betweens come to mediate everything.

As time goes on, we come to realize Sheeran is the wedge bewteen two of these unyielding forces, and he’s caught between a rock and a hard place. Between his “Rabbi” Russell, as Hoffa calls him, and the man he’s been through the trenches with — the man he asks to present his lifetime achievement award to him. He’s deeply loyal and beholden to both.

Is this his hamartia — his fatal flaw — that will become his undoing? We never quite know if he was able to make peace with any of it. All we know is something has to give…But I will leave it at that.

The unsung surprise of the film is the load of humor it manages end to end. Everyone is funny. The exchanges get outrageous to fit the larger-than-life characters and situations. It’s the kind of stuff you couldn’t make up if you tried. But the jokes play as a fine counterpoint to the grim reality of these men and their lifestyles.

In the later stages of life, as he prepares himself for death, Sheeran meets with a priest, which prove to be some of the most enlightening moments in the film. When asked if he has remorse, he matter-of-factly admits, not really, but even his choice to seek absolution is his attempt at something.

Scorsese continues in the stripe of Silence with some deeply spiritual and philosophical intercessions in what might otherwise seem a temporal and antithetical affair. The truth is you cannot come to terms with such a life — or any life — without grappling with the questions of the great unknown after death.

In another scene, Sheeran seeks out a casket and a resting place for his body muttering to himself just how final death is. That it’s just the end. It’s curious coming from a man who knocked off so many people, but somehow he’s just coming to terms with it himself. Perhaps it’s what old age does to one.

This is not meant to be any sort of hint or indication (we want more films), but if this were to be the last film this group of luminary talents ever made, I would be all but content. The film taps into content and themes that have been integral aspects of Martin Scorsese’s career since the beginning. Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and even Harvey Keitel are all synonymous with the crime film — they share a common thread — a communal cinematic context and language.

My final thought is only this. The Irishman feels like Martin Scorsese’s Citizen Kane. I don’t mean it in the sense it’s his greatest film or the greatest film of all time. Rather, in a thematic sense, they are kindred. Although Scorsese’s version includes crime and violence, the ends results are very much the same.

You have a man with a life crammed full of power and money and recognition, whatever, but at the end of the day, what did it get him? He clings to dog-eared photos of his kids whom he probably hasn’t seen in years.

When the priest tells him he’ll be back after Christmas, Sheeran looks up at him pitifully, acknowledging he’ll be around. He’s not going anywhere. He has no family. He has no one to care about him. All his buddies are gone, and he’s the last of them holding onto secrets that do him no good. It’s all meaningless.

It’s a striking final image. All I could think was, “Oh, how the mighty have fallen.” Whether or not any of it was true (as the film seems to validate), what’s leftover is a paltry life. It’s a testament to everything we’ve witnessed thus far that we feel sorry for him.

4.5/5 Stars

As of late, it feels like the world has entered a bit of a Mr. Rogers Reinnaissance. He’s been gone since 2003 and yet last year we had Morgan Neville’s edifying documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? There are podcasts galore including Finding Fred and then Mr. Rogers’s words, whether before the Senate Committee or pertaining to scary moments of international tragedy, seem to still provide comfort and quiet exhortation to those in need.

As of late, it feels like the world has entered a bit of a Mr. Rogers Reinnaissance. He’s been gone since 2003 and yet last year we had Morgan Neville’s edifying documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? There are podcasts galore including Finding Fred and then Mr. Rogers’s words, whether before the Senate Committee or pertaining to scary moments of international tragedy, seem to still provide comfort and quiet exhortation to those in need. I Want to Live! calls upon the words of two men of repute to make an ethos appeal to the audience. The first quotation is plucked from Albert Camus. I’m not sure what the context actually was but the excerpt reads, “What good are films if they do not make us face the realities of our time.” This is followed up by some very official-looking script signed by Edward S. Montgomery, Pulitzer Prize winner, who confirms this is a factual story based on his own journalism and the personal letters of one Barbara Graham.

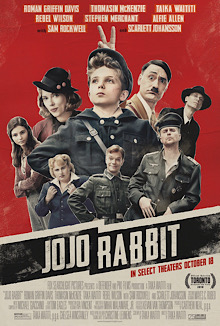

I Want to Live! calls upon the words of two men of repute to make an ethos appeal to the audience. The first quotation is plucked from Albert Camus. I’m not sure what the context actually was but the excerpt reads, “What good are films if they do not make us face the realities of our time.” This is followed up by some very official-looking script signed by Edward S. Montgomery, Pulitzer Prize winner, who confirms this is a factual story based on his own journalism and the personal letters of one Barbara Graham. We must acknowledge the elephant, or rather, the rabbit, in the room. Grappling with the intersection of Nazis and humor has always been a loaded and controversial topic. But usually, it fosters conversation nonetheless so here’s an attempt to provide some meager context.

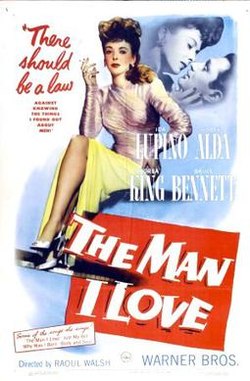

We must acknowledge the elephant, or rather, the rabbit, in the room. Grappling with the intersection of Nazis and humor has always been a loaded and controversial topic. But usually, it fosters conversation nonetheless so here’s an attempt to provide some meager context. It feels like we might have the courtesy of a bit of Gershwin masquerading under the cloak of noir. We find ourselves at a hole-in-the-wall jazz joint after hours. Club 39 feels free and easy with an intimate jam sesh. Petey Brown (Ida Lupino) is having fun with a rendition of “The Man I Love.”

It feels like we might have the courtesy of a bit of Gershwin masquerading under the cloak of noir. We find ourselves at a hole-in-the-wall jazz joint after hours. Club 39 feels free and easy with an intimate jam sesh. Petey Brown (Ida Lupino) is having fun with a rendition of “The Man I Love.” Of the plethora of returning G.I. films and film noirs, this one reflects their fears most overtly and for this very reason, it might be generally the most forgotten today. That and the assembly of a lower-tier cast. Most of these names have been lost to time.

Of the plethora of returning G.I. films and film noirs, this one reflects their fears most overtly and for this very reason, it might be generally the most forgotten today. That and the assembly of a lower-tier cast. Most of these names have been lost to time.

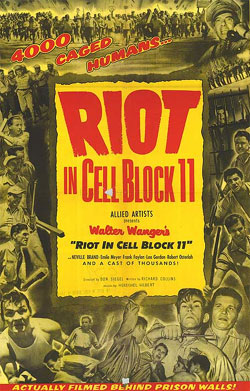

If you’re like me you met Don Siegel because of Dirty Harry (1971) or maybe The Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). But it was only after discovering the rest of his work — the likes of The Big Steal (1949), The Lineup (1958), or even this film, where you began to appreciate the consummate craftsman that he was.

If you’re like me you met Don Siegel because of Dirty Harry (1971) or maybe The Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). But it was only after discovering the rest of his work — the likes of The Big Steal (1949), The Lineup (1958), or even this film, where you began to appreciate the consummate craftsman that he was.

NOTE: I’m never too concerned about spoilers but just be warned I’m talking about The Irishman, which will come out in November. If you want to be surprised maybe wait to read this…

NOTE: I’m never too concerned about spoilers but just be warned I’m talking about The Irishman, which will come out in November. If you want to be surprised maybe wait to read this…