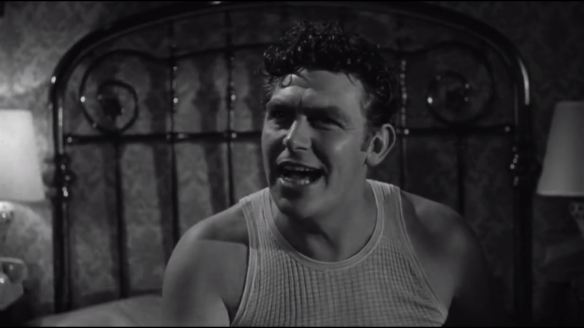

It begins unobtrusively enough. In a backwater Arkansas jail, a drunkard plays his guitar on a radio segment of “A Face in the Crowd” being broadcast from his cell. They don’t know it quite yet but soon the host who found him, Marcia Jeffries (Patricia Neal), and Larry “Lonesome” Rhodes (Andy Griffith) capture the public’s imagination. Far from just plucking Rhodes out of obscurity, Jefferies also rebrands him with an off the cuff remark and uses her daddy’s radio reach to broadcast him all around.

With such a platform, Rhodes does the rest with his wild whoops of down-home charm and strangely beguiling magnetism. He’s a natural performer and showman who knows how to form a connection with the folks at home. Soon they have created a following or as is popular in the lexicon these days a “tribe” giving him real media presence in the cultural conversation.

Someone asks him the question, “How does it feel to be able to say anything that comes into your head and be able to sway people?” But it’s true. He’s at the forefront of a grassroots democracy turning into a television phenomenon.

Meanwhile, Jefferies watches it all unfolding with bright-eyed awe and deep enthusiasm. It’s absolutely rich seeing it sweep over the country. One of the cogs in the machine is a jaded writer named Mel (an early Walter Matthau) who watches the unfoldings with grim amusement. Meanwhile, Lonesome’s ever-ambitious and cutthroat promoter (an even younger Anthony Franciosa) positions his man to continue broadening his success. Everyone’s trying to get a piece of this new pie. Because what’s more American than pie?

Rhodes keeps up his side of the bargain by purveying his own brand of “authenticity.” On one show he brings on a destitute African-American woman and gives a call-to-action and the money comes pouring in, in response. Another week he crosses a mattress sponsor and subsequently raises the man’s sales all across the country simply by belittling his product.

Soon he’s brought on to promote the product of the stuffy Vitajex company and he takes their pride and joy, disregarding their focus groups and tradition, selling the pill straight to the public. By the time he’s done with them, the public’s buying them up by the barrelful.

He also captures the imaginations and the fancy of all the young girls all across the nation — soon has them all swooning over him — but one lucky girl wins out (Lee Remick) with her baton twirling during the Ms. Arkansas Majorrette competition of 1957. Of course, Lonesome Rhodes is made the judge and after getting mobbed by the girls, he takes a shine to Betty Lou.

Marcia gets pushed further and further into the periphery of his life as Rhodes weds the frisky twirler and sets his sights on the next domain to be conquered. Politics have entered a new stage — the television age — and no man is more beloved than Lonesome Rhodes. “You gotta be a saint for the power the box can give you,” as Mel notes, and in the wrong hands, this immense power is dangerous.

Rhodes throws his support behind a stodgy old lawmaker giving him advice in the process. The film was already predicting the famed televised debate between Nixon and Kennedy. Where campaigning is about punchlines and glamor; it becomes a popularity contest and an advertising endeavor as much as a smear campaign. He uses his Cracker Barrel Show to promote the senator in a more relaxed atmosphere and has the position of Secretary of National Morale waved in front of him.

He even notes his candidate should get a dog, observing that it didn’t do Roosevelt any harm or Dick Nixon neither (referring to the well-received “Checkers” speech in 1952). Because these events begin to hint out how corruption, even double talk, begin to make the general public question “authenticity.”

In one off-handed remark, Lonesome crows, “This whole country is just like my flock of sheep.” However, like Arthur Godfrey, his downfall (though more rapid) occurs after an onscreen incident that removes his mask and undermines his image before the people. They can never see him the same way. The saboteur, as it were, is Marcia for she cannot bear to see the people taken in.

So the final trajectory is obvious — the ascension and the dethronement — but that can hardly neutralize what we have already witnessed. A Face in the Crowd lingers with fair warning, relevant to any analogous situation in the modern landscape, only magnified to the nth degree.

Earl Hagen’s down-home waterhole tunes fit The Andy Griffith Show just as this arrangement from Tom Glazer gels with A Face in the Crowd. Speaking of, I must insert a thought on what I know more about, as I grew up watching countless hours of The Andy Griffith Show.

The character of Andy Taylor obscures the fact of what a fine actor Andy Griffith was. To some extent, the same can be said of No Time for Sergeants because like the early seasons of his show, he’s just playing a bubble-headed hick. Later on, he became more of a straight man and after Barney Fife left, he settled into a more irascible role so there was an evolution.

Regardless, Lonesome Rhodes turns the overarching stereotypes of the man on their head. You can still see him as the benevolent Sheriff of Mayberry but this certainly lingers in the back of your mind. Take away the moral integrity and others-centric mentality of Andy and you wind up with Lonesome.

Given its themes about media and television, which seem like a cutting-edge indictment in their contemporary age, it seems logical to lump A Face in The Crowd with Network. Similarly, though technology and advertising continue to become more advanced and invasive, the themes explored feel, not less relevant, but more so.

We simply have to magnify them. Instead of television, we have Twitter and smartphones. Instead of people who willfully hide their intent, we have people in power who seem to blatantly disregard moral uprightness.

I want Lonesome Rhodes to be outdated and immaterial but to make such a claim would be an immense act of folly. It would cater to the same sense of ignorance and sway in all sectors of society, which led to the rise of such a person in the first place. Then and now…

4.5/5 Stars

Note: An earlier version of this review erroneously said Rip Torn instead of Anthony Franciosa (He was featured in an uncredited role).

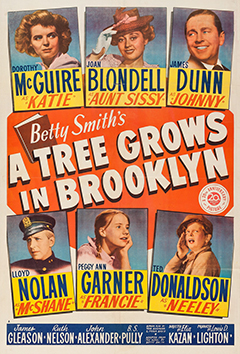

The reveries of a Saturday afternoon in childhood are where A Tree Grows in Brooklyn chooses to begin and it proves a fine entry point, giving us an instant feel for the world the Irish neighborhood of Williamsburg in Brooklyn. Its contours are impoverished, even harsh, but also richly American.

The reveries of a Saturday afternoon in childhood are where A Tree Grows in Brooklyn chooses to begin and it proves a fine entry point, giving us an instant feel for the world the Irish neighborhood of Williamsburg in Brooklyn. Its contours are impoverished, even harsh, but also richly American. Since the dawn of man, the vast reaches of the cosmos up above have enamored us to the nth degree. You need only watch something like 2001 to be reminded of that fact. (There’s no doubt James Gray is well-versed in its frames.)

Since the dawn of man, the vast reaches of the cosmos up above have enamored us to the nth degree. You need only watch something like 2001 to be reminded of that fact. (There’s no doubt James Gray is well-versed in its frames.)

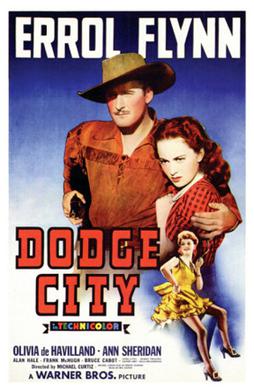

The year is 1866. The Civil War is over and anyone with vision is moving west. One such outpost is Kansas where the railway is replacing the stagecoach. It’s a world of iron men and iron horses. Because a place like the notorious Dodge City is a “town that knew no ethics but cash and killing.”

The year is 1866. The Civil War is over and anyone with vision is moving west. One such outpost is Kansas where the railway is replacing the stagecoach. It’s a world of iron men and iron horses. Because a place like the notorious Dodge City is a “town that knew no ethics but cash and killing.” The western is founded on certain unifying archetypes, from drifters to revenge stories, showdowns and the westward progress of civilization butting up against the lawless wilderness. It always proved a fitting genre for morality plays and deeply thematic ideas. The tradition of the bank robbery goes back to Edwin S. Porter and The Great Train Robbery, and it plays an important role in The Naked Dawn.

The western is founded on certain unifying archetypes, from drifters to revenge stories, showdowns and the westward progress of civilization butting up against the lawless wilderness. It always proved a fitting genre for morality plays and deeply thematic ideas. The tradition of the bank robbery goes back to Edwin S. Porter and The Great Train Robbery, and it plays an important role in The Naked Dawn.

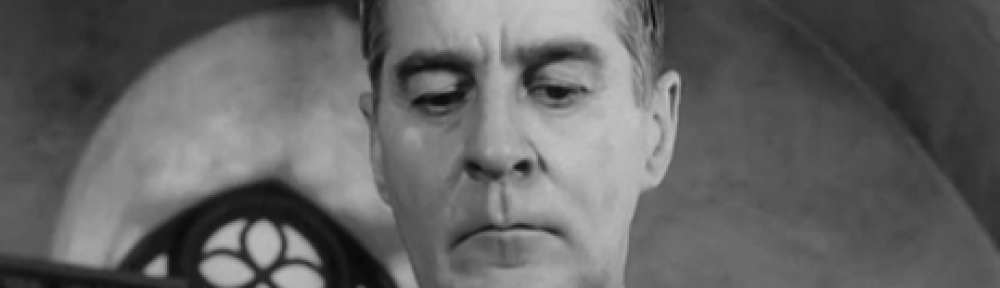

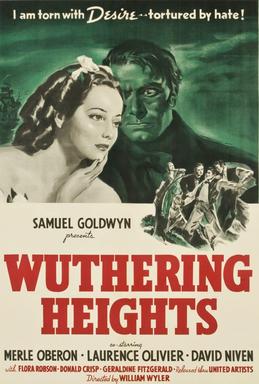

It’s almost instantly reasonable to clump this cinematic adaptation of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights with other contemporary pictures swirling with gothic menace like Rebecca, Suspicion, and Jane Eyre. The latter film, of course, is based off the novel of another of the Bronte Sisters, Charlotte.

It’s almost instantly reasonable to clump this cinematic adaptation of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights with other contemporary pictures swirling with gothic menace like Rebecca, Suspicion, and Jane Eyre. The latter film, of course, is based off the novel of another of the Bronte Sisters, Charlotte.