The initial inclination for seeing Arnaud Desplechin’s sprawling family drama was the presence of the estimable Catherine Deneuve. And she’s truly wonderful giving a shining, nuanced performance that makes the audience respect her, sympathize with her, and even dislike her a little bit. But the same goes for her entire family. The best word to describe them is messy. Dysfunctional is too sterile. Messy fits what they are. If you think your family is bad around the holidays, the Vuillards have a lot of their own issues to cull through.

The initial inclination for seeing Arnaud Desplechin’s sprawling family drama was the presence of the estimable Catherine Deneuve. And she’s truly wonderful giving a shining, nuanced performance that makes the audience respect her, sympathize with her, and even dislike her a little bit. But the same goes for her entire family. The best word to describe them is messy. Dysfunctional is too sterile. Messy fits what they are. If you think your family is bad around the holidays, the Vuillards have a lot of their own issues to cull through.

The inciting incident sends a shock wave through their already crumbling family unit. Their matriarch has been diagnosed with bone marrow cancer and must make the difficult decision of whether or not to risk treatment or go without. But Deneuve carries herself with that same quietly assured beauty that she’s had even since the days of Umbrellas of Cherbourg. In this capacity, she makes A Christmas Tale, far from a tearful, sobfest. She’s strong, distant, and you might even venture to say fearless.

And because of her strength, this story is not only about her own plight – it’s easy to downplay it because she is so resilient – but it frames the rest of the interconnecting relationships. It began when her first son passed away. The children who followed included Elizabeth (Anne Cosigny) who became the oldest and grew up to be a successful playwright. Junon’s middle child Henri (Mathieu Amalric) can best be described as the black sheep while the youngest, Ivan, was caught in the midst of the familial turmoil.

Because the issues go back at least five years before Junon gets her life-altering news. It was five years ago that Elizabeth paid Henri’s way out of an extended prison sentence (for a reason that is never explained) with the stipulation that she never has to see her brother again. Not at family gatherings, not for anything. And she gets her way for a time.

But with Junon’s news she and her husband Abel (Jean-Paul Roussillon) realize this is a crucial time to get their family back together because, above all, their matriarch needs a donor and due to her unique genetic makeup, a family member is her best bet.

Underlying these overt issues are numerous tensions that go beyond sibling grudges and sickness. Elizabeth’s own relationships have been fraught with unhappiness and her son Paul has been struggling through a bout of depression. Ivan and his wife (Chiarra Mastroianni) are seemingly happy with two young boys of her own. But old secrets about unrequited love get dredged up and Sylvia is looking for answers of her own. Although it’s a side note, it’s striking that Chiarra Mastroianni is Deneuve’s real-life daughter and in her eyes, I see the spitting image of her father, the icon, Marcello Mastroianni.

There’s also a lot of truth and honesty buried within A Christma Tale and in most competitions, it would win for the most melancholy of yuletide offerings. However, it’s important to note that its darkness is balanced out with romance, comedy, and a decent dose of apathy as well.

Still, the most troubling thing about A Christmas Tale is not the fact that it is extremely transparent, but the reality that the themes of Christmas have no bearing on its plot. We leave these characters different than they were before but whether they are better for it is up for debate.

The sentimentality of a It’s Wonderful Life crescendo would be overdone and fake in this context but some sort of reevaluation still seems necessary. Because without faith in anything — faith in their family is ludicrous — their world looks utterly hopeless. The two little grandsons wait in front of the nativity staying up to get a glimpse at Jesus (perhaps mistaken for Santa Claus) and their father calmly states they should go to bed because he’s never existed anyways. And there’s nothing inherently wrong with holding such beliefs.

Even the fact that Junon and her grown son Henri attend midnight mass is an interesting development. But during this season emblematic of hope and joy, it seems like the Vuillard’s can have very little of either one. Henri can be his mother’s savior for a time by extending her life for 1.7 years or whatever the probabilities suggest. But then what?

It’s this reason and not the family drama that ultimately makes A Christmas Tale a downer holiday story. Its denouement feels rather like a dead end more than fresh beginnings. Because Nietzche and coin flips are not the most satisfying ways to decipher the incomprehensibility of life – especially with death looming large during the holidays.

But that’s only one man’s opinion. That’s not to downplay all that is candid about this film in any way. If you are intrigued by the interpersonal relationships and entanglements of a family — may be a lot like yours and mine — this film is an elightening exposé.

3.5/5 Stars

Almost Famous is almost so many things. There are truly wonderful moments that channel certain aspects of our culture’s infatuation with rock n roll.

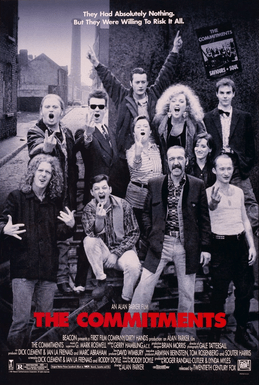

Almost Famous is almost so many things. There are truly wonderful moments that channel certain aspects of our culture’s infatuation with rock n roll. The Commitments is a very coarse film, extremely rough around the edges, and yet to its credit, the real appeal of this crowd-pleaser from Alan Curtis is the way that music is able to bring so much good into a dire situation. Because in some ways The Commitments are not just the christened “Saviors of Soul” but for one brief shining moment, they’re the “Saviors of Dublin” too.

The Commitments is a very coarse film, extremely rough around the edges, and yet to its credit, the real appeal of this crowd-pleaser from Alan Curtis is the way that music is able to bring so much good into a dire situation. Because in some ways The Commitments are not just the christened “Saviors of Soul” but for one brief shining moment, they’re the “Saviors of Dublin” too. “A picture with a smile — and perhaps, a tear…”

“A picture with a smile — and perhaps, a tear…”

In Manchester by the Sea, you can distinctly see Kenneth Lonergan once more translating some of his skills as a playwright and stage director into his film. There’s a very inherent understanding of two-dimensional space and how images can be framed in a very linear way as they would be seen by an audience taking in a stage production. But even more noteworthy than that is his dialogue which functions in remarkably realistic ways. Some will easily write this film off as the sheer doldrums because it’s fairly fearless in its pacing.

In Manchester by the Sea, you can distinctly see Kenneth Lonergan once more translating some of his skills as a playwright and stage director into his film. There’s a very inherent understanding of two-dimensional space and how images can be framed in a very linear way as they would be seen by an audience taking in a stage production. But even more noteworthy than that is his dialogue which functions in remarkably realistic ways. Some will easily write this film off as the sheer doldrums because it’s fairly fearless in its pacing. Upon watching A Few Good Men for the first time, it was hard not to draw parallels with An Officer and a Gentlemen for some reason and it went beyond some cursory elements such as both films involving branches of the military. Perhaps more so than that is the intensity that manages to surge through the plot despite the potentially stagnant battleground like Cadet Schools, Courtrooms, and the like. And that can in both cases is a testament to the stellar performances in front of the camera.

Upon watching A Few Good Men for the first time, it was hard not to draw parallels with An Officer and a Gentlemen for some reason and it went beyond some cursory elements such as both films involving branches of the military. Perhaps more so than that is the intensity that manages to surge through the plot despite the potentially stagnant battleground like Cadet Schools, Courtrooms, and the like. And that can in both cases is a testament to the stellar performances in front of the camera. Patterns has little right to be any good. It takes place almost exclusively in interiors. Boardrooms, offices, hallways, at desks, and in elevators. But thanks to a fantastic teleplay from Twilight Zone mastermind Rod Serling, this little picture exceeds the meager expectations placed on it. In fact, it was a major hit when it came out as a live television drama, so successful that it was performed a second time and subsequently developed into this film version.

Patterns has little right to be any good. It takes place almost exclusively in interiors. Boardrooms, offices, hallways, at desks, and in elevators. But thanks to a fantastic teleplay from Twilight Zone mastermind Rod Serling, this little picture exceeds the meager expectations placed on it. In fact, it was a major hit when it came out as a live television drama, so successful that it was performed a second time and subsequently developed into this film version. Whatever our criticisms of the previous generations, there’s still something within me that sees something uniquely compelling about films of old. Hollywood in the 30s and 40s could sugar coat, they could oversell the drama, but there was also a general decency that pervaded many of those films.

Whatever our criticisms of the previous generations, there’s still something within me that sees something uniquely compelling about films of old. Hollywood in the 30s and 40s could sugar coat, they could oversell the drama, but there was also a general decency that pervaded many of those films.