Like the fella says, in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love – they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.

Like the fella says, in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love – they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.

Great films ring anew each time you see them. Or in this case, they twang with the oddly disconcerting strains of zither strings. The Third Man is such a film that continually asserts itself as one of the golden classics of the 1940s. But we must set the scene.

There’s an image of a great city–a formerly great city–blown up, diced up, and quartered. The first syllable of dialogue glibly carrying a twinge of irony lays the groundwork for the entire plot really. This is Post-war Vienna. It’s where the blown out buildings strewn with rubble can exist with the elegant remnants of royal dynasties. A land of black marketeering and shifty-eyed collaboration between wartime allies. It’s deception and ambiguity to the nth degree not only evident in the people but the very social structure they find themselves in. Everyone’s got an angle, a secret to hide, and a reason to hide it. There’s a consistently fine line between right and wrong and the storyline is ripe with incongruities and dissonance that, if nothing else, are disconcerting.

It struck me that this is the original Chinatown except it doesn’t simply act as a mere metaphor. We actually get enveloped in the atmospheric Vienesse world that feels invariably gaunt and hollow. It’s a world that’s flipped upside down and with the hapless American western pulp novelist Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) as our guide, we become just as mixed up as he does.

He’s come to the town for the prospects of a job offered by an old school chum Harry Lime. But Harry’s not there to meet him. In fact, Harry’s not anywhere. He’s dead. But everything is clouded with that same ambiguity. The military police led by Inspector Calloway (Trevor Howard) and his right hand man (Bernard Lee) are still investigating Lime’s prior dealings on the black market in tainted penicillin. Meanwhile, Martins obviously goes blundering around trying to learn anything he can because these men are obviously incompetent. He scouts around for eyewitnesses and several of Lime’s acquaintances. Most of all he’s taken with Harry’s gal Anna (Valli) who is also torn apart by the death of her Harry. They bond over that although Holly soon becomes infatuated with her as she remains in love with a man who is gone forever.

This is the disorienting world that we are thrown into by Graham Green and director Carol Reed. Where heaven is down and hell is up. Ferris Wheels ever turning, rotating through their cycles. Dutch angles giving every figure a contorted view. We never see anyone for their face value and we can never assume anything. Because there’s always something lurking in the shadows.

Joseph Cotten is surprisingly compelling as the poor, unfortunate stiff and it’s hard not to feel sorry for him in his ignorance because we can relate with him. Alida Valli is striking as the aloof beauty who nevertheless has an unswerving affection for her former love that remains the only joyous thing in her current existence. Then, of course, there’s Orson Welles as the charismatic myth of a man–arguably the most intriguing supporting character there ever was even if it’s mostly thanks to the legend created by those who knew him.

Joseph Cotten is surprisingly compelling as the poor, unfortunate stiff and it’s hard not to feel sorry for him in his ignorance because we can relate with him. Alida Valli is striking as the aloof beauty who nevertheless has an unswerving affection for her former love that remains the only joyous thing in her current existence. Then, of course, there’s Orson Welles as the charismatic myth of a man–arguably the most intriguing supporting character there ever was even if it’s mostly thanks to the legend created by those who knew him.

Meanwhile, Carol Reed’s film is stylish and simultaneously dingy around the edges another gritty entry in the annals of film noir with some of the most beautifully pronounced shadows in the history of film. The final setpiece through the dank cavernous underworld of the Viennese sewers is a fitting place for the Third Man’s climatic moments to play out. It epitomizes all that has been going on above ground so far.

Then in a strikingly Deja Vu moment, the story ends much as it began in the exact same place with the exact same people but now there is so much more tension underlying each character. Feelings now buried in the dirt.

And in his final shot, Reed is fearless. He plays a game with the audience, giving them their final shot but instead of bringing it to a rapid conclusion he lets the gravity of the situation sink in before it’s gone in a fit of wistful melancholy. It ends as all films noir should with one man dead, another man smoking a cigarette, and the girl walking off with neither of them. It’s about as bleak as you can get but then again we’ve already spent the entire film getting accustomed to this lifestyle. This is only a day in the life of a city like Vienna. This is what life is in a post-war zone.

5/5 Stars

Note: I will say that I rewatched the film on Netflix and I would vehemently dissuade others from doing the same (at least if they’ve never seen The Third Man before). Because one major change they made that you would hardly even think about is adding subtitles in some crucial moments. When I saw the film multiple times before the lack of subtitles only added to my general sense of confusion in the face of ambiguities, much like Holly Martins faces himself. Subtitles take some of that away from us as an audience. In this case, the subtitles are tantamount to colorizing black & white movies or resorting to pan and scan. They can easily ruin the experience.

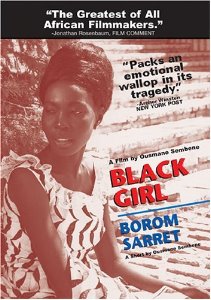

What’s fascinating about this film is how it manages to give voice to those who are normally silenced and even in her subservience this narrative powerfully lends agency to a young Senegalese woman’s perspective. Because even when she is silent and words are not coming out of her mouth and her status ultimately makes her powerless, the very fact that her mind is constantly thinking, her eyes observing and so on mean something. Inherently there’s a great empowerment found there even if it’s only known by her and seen by the outside observer peering into her life. That’s part of her. We are given a view into what she sees. We can begin to understand her helplessness and isolation. Where she came from and the life she left behind. Giving up the master narrative of the entitled and shown the flip side of the world for once.

What’s fascinating about this film is how it manages to give voice to those who are normally silenced and even in her subservience this narrative powerfully lends agency to a young Senegalese woman’s perspective. Because even when she is silent and words are not coming out of her mouth and her status ultimately makes her powerless, the very fact that her mind is constantly thinking, her eyes observing and so on mean something. Inherently there’s a great empowerment found there even if it’s only known by her and seen by the outside observer peering into her life. That’s part of her. We are given a view into what she sees. We can begin to understand her helplessness and isolation. Where she came from and the life she left behind. Giving up the master narrative of the entitled and shown the flip side of the world for once. Prior to the making and release of Monsieur Verdoux Charlie Chaplin had undoubtedly hit the most turbulent patch in his historic career and not even he could come out of scandal and political upheaval unscathed. To put it lightly his stock in the United States plummeted.

Prior to the making and release of Monsieur Verdoux Charlie Chaplin had undoubtedly hit the most turbulent patch in his historic career and not even he could come out of scandal and political upheaval unscathed. To put it lightly his stock in the United States plummeted. The glamour of limelight, from which age must pass as youth centers

The glamour of limelight, from which age must pass as youth centers  But now no one’s there. The seats are empty, the aisles quiet, and he sits with a dazed look in his flat the only recourse but to go back to bed. It’s as if the poster on the wall reading Calvero – Tramp Comedian is paying a bit of homage to his own legend but also the very reality of his waning, or at the very least, scandalized stardom. It adds insult to injury.

But now no one’s there. The seats are empty, the aisles quiet, and he sits with a dazed look in his flat the only recourse but to go back to bed. It’s as if the poster on the wall reading Calvero – Tramp Comedian is paying a bit of homage to his own legend but also the very reality of his waning, or at the very least, scandalized stardom. It adds insult to injury. It’s important to know that he writes off such an assertion as nonsense and one can question whether this is Chaplin’s chance at revisionist history or more so an affirmation of his life’s actual trajectory–working through his current reality that the world questions (IE. Marrying a woman much younger than himself in Oona O’Neil who he nevertheless dearly loved).

It’s important to know that he writes off such an assertion as nonsense and one can question whether this is Chaplin’s chance at revisionist history or more so an affirmation of his life’s actual trajectory–working through his current reality that the world questions (IE. Marrying a woman much younger than himself in Oona O’Neil who he nevertheless dearly loved). Blanche Dubois and Stanley Kowalski. They’re both so iconic not simply in the lore of cinema history but literature and American culture in general. It’s difficult to know exactly what to do with them. Stanley Kowalski the archetypical chauvinistic beast. Driven by anger, prone to abuse, and a mega slob in a bulging t-shirt who also happens to be a hardline adherent to the Napoleonic Codes. But then there’s Blanche, the fragile, flittering, self-conscious southern belle driven to the brink of insanity by her own efforts to maintain her epicurean facade. They’re larger than life figures.

Blanche Dubois and Stanley Kowalski. They’re both so iconic not simply in the lore of cinema history but literature and American culture in general. It’s difficult to know exactly what to do with them. Stanley Kowalski the archetypical chauvinistic beast. Driven by anger, prone to abuse, and a mega slob in a bulging t-shirt who also happens to be a hardline adherent to the Napoleonic Codes. But then there’s Blanche, the fragile, flittering, self-conscious southern belle driven to the brink of insanity by her own efforts to maintain her epicurean facade. They’re larger than life figures. Themla & Louise hardly feels like typical Ridley Scott fare but then again, neither is this a typical movie. It pulls from numerous genres that have been depicted countless times before from buddy movies to caper comedies, road films, and the like. But perhaps the intrigue begins with the two leads.

Themla & Louise hardly feels like typical Ridley Scott fare but then again, neither is this a typical movie. It pulls from numerous genres that have been depicted countless times before from buddy movies to caper comedies, road films, and the like. But perhaps the intrigue begins with the two leads. The last time I saw Hoosiers it was on VHS and I was only a boy and I hardly remember anything. Gene Hackman yelling. Dennis Hopper as a drunk. Jimmy the boy wonder, “The Picket Fence”, and of course Indiana basketball at its finest. But in those opening moments, as he drives into town and walks through the halls of his new home, I realized just how much I miss Gene Hackman. Yes, he’s still with us but the moment he decided to step out of the limelight and retire from his illustrious career as an actor, films got a little less exciting. His passionate often fiery charisma is dearly missed.

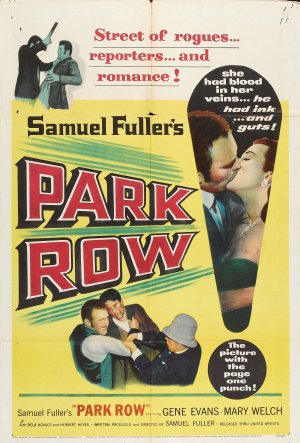

The last time I saw Hoosiers it was on VHS and I was only a boy and I hardly remember anything. Gene Hackman yelling. Dennis Hopper as a drunk. Jimmy the boy wonder, “The Picket Fence”, and of course Indiana basketball at its finest. But in those opening moments, as he drives into town and walks through the halls of his new home, I realized just how much I miss Gene Hackman. Yes, he’s still with us but the moment he decided to step out of the limelight and retire from his illustrious career as an actor, films got a little less exciting. His passionate often fiery charisma is dearly missed. It’s no secret that Sam Fuller cut his teeth in the journalism trade at the ripe young age of 18 (give or take a year) and so Park Row is not just another delicious B picture from one of the best, it’s a passion project memorializing the trade that he revered so dearly.

It’s no secret that Sam Fuller cut his teeth in the journalism trade at the ripe young age of 18 (give or take a year) and so Park Row is not just another delicious B picture from one of the best, it’s a passion project memorializing the trade that he revered so dearly. Initially, I Remember Mama comes off underwhelmingly. It’s overlong, there’s little conflict, and some of the things the story spends time teasing out seem odd and inconsequential at best. Still, within that framework is a narrative that manages to be rewarding for its utter sincerity in depicting the life of one family–a family that feels foreign in some ways and oh so relatable in many others.

Initially, I Remember Mama comes off underwhelmingly. It’s overlong, there’s little conflict, and some of the things the story spends time teasing out seem odd and inconsequential at best. Still, within that framework is a narrative that manages to be rewarding for its utter sincerity in depicting the life of one family–a family that feels foreign in some ways and oh so relatable in many others. Upon being thrown headlong into Christopher Nolan’s immersive wartime drama Dunkirk, it becomes obvious that it is hardly a narrative film like any of the director’s previous efforts because it has a singular objective set out.

Upon being thrown headlong into Christopher Nolan’s immersive wartime drama Dunkirk, it becomes obvious that it is hardly a narrative film like any of the director’s previous efforts because it has a singular objective set out.