“Nobody throws me my own guns and says ride on. Nobody” ~ James Coburn as Britt

“Nobody throws me my own guns and says ride on. Nobody” ~ James Coburn as Britt

People always resonate with stories of valor, honor, and bravery. It doesn’t matter if it’s a war film, a tale of samurai, or a western. Thus, Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai rather seamlessly became The Magnificent Seven, one of the most reputed westerns of the 1960s.

In theory & practice, it has everything you want in a western from a stellar cast to thrilling gunfights matched by one of the most epic soundtracks ever coming out of the annals of cinema.

But although it’s script is not exactly taut, you can hardly accuse The Magnificent Seven of being superficial. Its characters and its narrative are too satisfying for such a claim. After all, who wouldn’t want to see such a company as Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Horst Bucholtz, Charles Bronson, James Coburn, Robert Vaughan, and Brad Dexter? You have “The King and I,” “The King of Cool,” and about every other figure you would want in a good shoot’em up. They were seven who fought like 700.

In not completely splitting with its samurai roots, this western deals in moral codes and issues of honor perhaps more closely than even many of the best known western. The main issue here is that this laconic and sleek gang is brought together to defend a small Mexican border town made up of farmers against a bandit and his band of marauders. What causes men such as these to take on such a dangerous and in many ways such a one-sided job? For some it’s money (because they have none), some want the excitement, and for others, it’s something different. But all that matters is they all go into this together – some of the deadliest guns prepared to duke it out.

Into the valley road the seven rather like the light brigade, at first simply preparing to train up and prepare their little village of farmers to fight back against the brutal outlaw Calvera (Eli Wallach). But there’s something that happens over time. When you spend time in close proximity with people, eating their food and sharing their shelter, it’s hard not to build a bond — a connection that holds you there. At first, it seems of little consequence when the enemy gets beaten back, but everyone knows they will return with a vengeance.

Into the valley road the seven rather like the light brigade, at first simply preparing to train up and prepare their little village of farmers to fight back against the brutal outlaw Calvera (Eli Wallach). But there’s something that happens over time. When you spend time in close proximity with people, eating their food and sharing their shelter, it’s hard not to build a bond — a connection that holds you there. At first, it seems of little consequence when the enemy gets beaten back, but everyone knows they will return with a vengeance.

Ultimately, the seven are betrayed and are given a clear choice. They can keep moving on or turn back the way they came. It’s just a small inconsequential town, but they cannot turn their back on it, even when they were betrayed. They grapple with what’s good, what’s right, and what’s rational, and then make their decision. It goes against all reason and yet into the valley road the seven together (eventually).

And we get the final skirmish with guns blazing, bullets flying, and lives being put on the line. Here is a film where the final body count deeply matters. Not so much of the enemy, but of our heroes, because each one chisels out a little niche for themselves. Everyone has worth and importance even as they jockey for screen time and it pays off in the end. They fight with honor just as they die with honor. Perhaps it might seem futile, but not without significance. The little village is left in peace to live out their days in tranquility. Calvera’s final words echo in their ears: “You came back – for a place like this. Why? A man like you. Why?”

And we get the final skirmish with guns blazing, bullets flying, and lives being put on the line. Here is a film where the final body count deeply matters. Not so much of the enemy, but of our heroes, because each one chisels out a little niche for themselves. Everyone has worth and importance even as they jockey for screen time and it pays off in the end. They fight with honor just as they die with honor. Perhaps it might seem futile, but not without significance. The little village is left in peace to live out their days in tranquility. Calvera’s final words echo in their ears: “You came back – for a place like this. Why? A man like you. Why?”

Elmer Bernstein’s score is masterclass. Majestic, grand, playfully prancing about, and at the same time eliciting a grin from any boy who has ever dreamed of the Wild West. Furthermore, there are so many characters to idolize, because this film made ensemble action films the style along with the likes of The Great Escape, The Professionals, and The Dirty Dozen to name a few. This has always been one of my father’s favorite film’s and I can completely understand why. It has gunfights, bad guys, and good guys, quips, and tricks. But at the most basic level, it’s a striking parable about moral codes, personal pride, and the sacrifice that goes along with such things.

4.5/5 Stars

I still remember driving through the hills and dales of the English countryside listening to Hard Day’s Night in the family rental car. Back then I had a haircut that could best be described as a mop top. And then during my one visit to Liverpool, I was beyond ecstatic. I’m a fairly reserved person and yet standing in Paul McCartney’s kitchen at 20 Forthlin Road (his childhood residence) what else could I do but bend down and kiss the floor?

I still remember driving through the hills and dales of the English countryside listening to Hard Day’s Night in the family rental car. Back then I had a haircut that could best be described as a mop top. And then during my one visit to Liverpool, I was beyond ecstatic. I’m a fairly reserved person and yet standing in Paul McCartney’s kitchen at 20 Forthlin Road (his childhood residence) what else could I do but bend down and kiss the floor? What it manages to bring together within the frame of a meager B-film plot is quite astounding, balancing the brutality and atmospheric visuals with the direction of Robert Wise to develop something quite memorable. Boxing movies have been bigger and better, but film-noir has a way of dredging up the grittiest pulp and the Set-Up is that kind of film.

What it manages to bring together within the frame of a meager B-film plot is quite astounding, balancing the brutality and atmospheric visuals with the direction of Robert Wise to develop something quite memorable. Boxing movies have been bigger and better, but film-noir has a way of dredging up the grittiest pulp and the Set-Up is that kind of film.

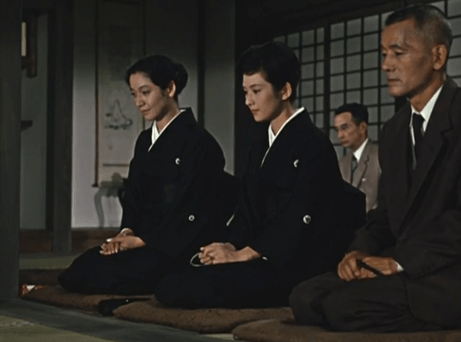

High and Low (or Heaven and Hell in the original Japanese) is a yin and yang film about the polarity of man in many ways. Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) is an affluent executive in the National Shoe Company. He worked his way up the corporate ladder from the age 16, because of his determination and commitment to a quality product. Now his colleagues want his help in forcing the company’s czar out. They come to his modernistic hilltop abode to get his support. Instead, they receive his ire, splitting in a huff. What follows is a risky plan of action from Gondo that is both fearless and shrewd. He takes all his capital to buy stock in the company so he can take over, but his whole financial stability hangs in the balance. He knows exactly what it means, but he wasn’t suspecting certain unforeseen developments.

High and Low (or Heaven and Hell in the original Japanese) is a yin and yang film about the polarity of man in many ways. Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) is an affluent executive in the National Shoe Company. He worked his way up the corporate ladder from the age 16, because of his determination and commitment to a quality product. Now his colleagues want his help in forcing the company’s czar out. They come to his modernistic hilltop abode to get his support. Instead, they receive his ire, splitting in a huff. What follows is a risky plan of action from Gondo that is both fearless and shrewd. He takes all his capital to buy stock in the company so he can take over, but his whole financial stability hangs in the balance. He knows exactly what it means, but he wasn’t suspecting certain unforeseen developments. At this point, the police are called and they arrive incognito, ready to stake out the joint and do the best they can to get the boy back safe and sound. This section of the film almost in its entirety takes place within the confines of Gondo’s house and namely the front room overlooking the city. It’s the perfect set up for Akira Kurosawa to situate his actors. He uses full use of the widescreen and his fluid camera movements keep them perfectly arranged within the frame.

At this point, the police are called and they arrive incognito, ready to stake out the joint and do the best they can to get the boy back safe and sound. This section of the film almost in its entirety takes place within the confines of Gondo’s house and namely the front room overlooking the city. It’s the perfect set up for Akira Kurosawa to situate his actors. He uses full use of the widescreen and his fluid camera movements keep them perfectly arranged within the frame. Finally, with the help of Shinichi, they make a startling discovery that ties back to the kidnapper. And the boy’s drawings along with a colorful stream of smoke help them move in ever closer. What follows is an elaborate web of trails through the streets as they work to catch the culprit in his crime, to put him away for good. And it works.

Finally, with the help of Shinichi, they make a startling discovery that ties back to the kidnapper. And the boy’s drawings along with a colorful stream of smoke help them move in ever closer. What follows is an elaborate web of trails through the streets as they work to catch the culprit in his crime, to put him away for good. And it works. But High and Low cannot end there without a consideration of the consequences. Gondo has been brought low. He’s losing his mansion and must start a new job on the bottom of the food chain once more. His enemy requests a final meeting as he prepares for his imminent fate, and this is perhaps the most grippingly painful scene. Gondo’s face-to-face with the man who made him suffer so much. Toshiro Mifune’s violent acting style serves him well as he wrestles so intensely with his own conscience. And yet at this junction, he is past that. What is he to do but listen? In this way, it’s difficult to know who to feel sorrier for — the man who is resigned to a certain fate passively or the one who goes out proud and arrogantly against death. Both have entered some dark territory and it’s no longer about high or low or even heaven and hell. They’re stuck in some middle ground. An equally frightening purgatory.

But High and Low cannot end there without a consideration of the consequences. Gondo has been brought low. He’s losing his mansion and must start a new job on the bottom of the food chain once more. His enemy requests a final meeting as he prepares for his imminent fate, and this is perhaps the most grippingly painful scene. Gondo’s face-to-face with the man who made him suffer so much. Toshiro Mifune’s violent acting style serves him well as he wrestles so intensely with his own conscience. And yet at this junction, he is past that. What is he to do but listen? In this way, it’s difficult to know who to feel sorrier for — the man who is resigned to a certain fate passively or the one who goes out proud and arrogantly against death. Both have entered some dark territory and it’s no longer about high or low or even heaven and hell. They’re stuck in some middle ground. An equally frightening purgatory.