Robert Mulligan is an unassuming film director. Man in the Moon would be his last film in a career that was not so much illustrious as it was respectable. In truth, I’ve only had the pleasure of seeing one of his other films — his crowning achievement To Kill a Mockingbird.

Robert Mulligan is an unassuming film director. Man in the Moon would be his last film in a career that was not so much illustrious as it was respectable. In truth, I’ve only had the pleasure of seeing one of his other films — his crowning achievement To Kill a Mockingbird.

There are in fact some similar threads running through these two films, starting with the Deep South nostalgia and close analysis of adolescence. Both these films take the point of view of a young girl. Their narratives hope to shed at least a little bit of light on that intricate stage of life. This time a 14-year-old Reese Witherspoon is our lead, playing the Elvis-loving, gum-chewing, spunky dynamo named Dani. She and Scout share a lot in common because as young people there’s an inherent tendency to mope, question, and disregard. They have not quite grabbed a hold of the mature world of their parents. After all, they still have a great deal to experience. That’s what makes these film arcs necessary.

Man in the Moon starts with Dani, but there’s a whole family unit around her. A father (Sam Waterson) who is a decent, down-to-earth-man, and he would rather commune with nature in his fishing boat than go to typical church. A mother (Tess Harper) who loves her husband and daughters dearly, knowing when to trade tough love for hugs. Maureen (Emily Warfield) is Dani’s oldest sister and her idol, along with the object of every local boy’s desire. She’s beautiful and yet what’s more extraordinary is her good nature. She doesn’t deserve the creepy father and son duo eyeing her in the local town.

Arguably, the next most important character in Dani’s story is Court (Jason London). They have your typical terse meet-cute that signifies only one thing. They must fall in love. It turns out he’s the eldest son of an old friend of Mrs. Trant. Soon things change for young Dani because she’s never known someone like Court, much less liked a boy.

Arguably, the next most important character in Dani’s story is Court (Jason London). They have your typical terse meet-cute that signifies only one thing. They must fall in love. It turns out he’s the eldest son of an old friend of Mrs. Trant. Soon things change for young Dani because she’s never known someone like Court, much less liked a boy.

Their relationship is one of those complicated entanglements. He’s a few years older and is the man of the house. He has to grow up quickly and views Dani as a child. But their friendship blossoms with frolicking afternoon swims. Dani is ready for something more. She thinks she’s in love. Now if Court was one of the other boys, he could easily take advantage of the situation — this fawning girl who is madly in love with him. But he’s not like that. Dani can’t quite get that through her head. It just doesn’t make sense. They enter friend territory and Dani’s heart is still aflutter, but she’s happy again.

The second half of the film enters melodramatic territory that first hits the Trant’s with familial turmoil, and then Court. Dani for the first time in her life is faced with the full brunt of tribulation. What makes matter worse is her feelings are all mixed up. She loves her sister. She hates her sister. She cannot bear to see Court. She cannot bear the suffering. It’s in these moments that uncomfortable feeling well up in the pit of your stomach.

The second half of the film enters melodramatic territory that first hits the Trant’s with familial turmoil, and then Court. Dani for the first time in her life is faced with the full brunt of tribulation. What makes matter worse is her feelings are all mixed up. She loves her sister. She hates her sister. She cannot bear to see Court. She cannot bear the suffering. It’s in these moments that uncomfortable feeling well up in the pit of your stomach.

Man in the Moon like many of the great coming-of-age movies is really about adolescents coming out of their innocence and being inundated with the often frightening realities of life. It reminds even the youngest of us that more often than not life is unmerciful. It’s how we pick ourselves up out of that fatality that matters. It’s hard but that pain is often how we grow and mature — learning how to cope with the way things are. That’s what makes the people around us so integral to existence. They can be our lifeline that keeps us afloat. Thus, Dani’s friendship with Court matters so much. That’s why Dani’s relationship with Marie matters too.

Perhaps the drama is laid on rather thick, but nevertheless, it’s difficult not to get behind this film. Reese Witherspoon’s perkiness is wonderfully disarming, and Jason London plays a decent young man. These are characters I want to watch and emulate. Not quite Scout and Atticus, but they are still definitely worth the time.

4/5 Stars

You’ve got a right to grieve, Dani. You got a right to be hurt. But if you get so wrapped up in your own pain that you can’t see anyone else’s, then you might just as well dig yourself a hole and pull the dirt in on top of you, because you’re never going to be much use to yourself or anyone else. ~ Mr. Trant

Note: This review previously said Marie (Gail Strickland) instead of Maureen (Emily Warfield)

Inherent in a film with this title, much like It’s a Wonderful Life, is the assumption that it is a generally joyous tale full of family, life, liberty, and the general pursuit of happiness. With both films you would be partially correct with such an unsolicited presumption, except for all those things to be true, there must be a counterpoint to that.

Inherent in a film with this title, much like It’s a Wonderful Life, is the assumption that it is a generally joyous tale full of family, life, liberty, and the general pursuit of happiness. With both films you would be partially correct with such an unsolicited presumption, except for all those things to be true, there must be a counterpoint to that. My Dinner with Andre was a film that was interesting in conception and not quite as engaging in practice — at least for me. The End of the Tour is another such conversation-driven story with a similar promise, but by some miracle, it really seems to pay off.

My Dinner with Andre was a film that was interesting in conception and not quite as engaging in practice — at least for me. The End of the Tour is another such conversation-driven story with a similar promise, but by some miracle, it really seems to pay off.

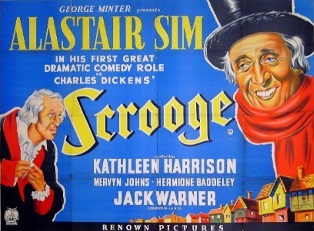

Oftentimes during the holidays, we are quick to label someone a “Scrooge,” almost jokingly because it’s a moniker that’s somehow lost a great deal of its magnitude with overuse and the passage of time. However, if we look at this film, so wonderfully anchored by Alastair Sim, and even Charles Dickens original work from which it is derivative, we would adopt a much wider definition of the word “Scrooge.”

Oftentimes during the holidays, we are quick to label someone a “Scrooge,” almost jokingly because it’s a moniker that’s somehow lost a great deal of its magnitude with overuse and the passage of time. However, if we look at this film, so wonderfully anchored by Alastair Sim, and even Charles Dickens original work from which it is derivative, we would adopt a much wider definition of the word “Scrooge.”