It’s a joy to watch Agnes Varda dance. Or, more precisely, it’s a joy to watch her camera dance. Because that’s exactly what it does. Her film opens in color, catching our attention, vibrant and alive as the credits roll and a young woman (Corinne Marchand) gets her fortune read by an old lady. She’s worried about her fate. We can gather that much and this is her way of coping. Superstition and tarot cards but she’s trying and the results are not quite to her fancy.

It’s a joy to watch Agnes Varda dance. Or, more precisely, it’s a joy to watch her camera dance. Because that’s exactly what it does. Her film opens in color, catching our attention, vibrant and alive as the credits roll and a young woman (Corinne Marchand) gets her fortune read by an old lady. She’s worried about her fate. We can gather that much and this is her way of coping. Superstition and tarot cards but she’s trying and the results are not quite to her fancy.

And from that point on Varda’s camera continues to move dynamically but her film quickly turns to black and white as if to say something. Our main heroine, this young, attractive singer named Cleo has sunk into a sense of despondency. For the next two hours, she must wait it out to hear the news from her doctor. The news being whether or not she has been stricken with cancer. And if cancer then recovery or even….death. This is her existential crisis.

In the following moments, the camera falls back as an observer even donning her point of view from time to time and that’s the true enjoyment of this film. There are stakes laid out right from beginning and those remain in the back of our minds but it’s really about how we get there. How she gets there.

Cleo walks the streets of Paris browsing shop windows for hats, taking cab rides through the city, patronizing local establishments, resting at her flat with her assistant, and even calling on friends.

It becomes obvious that Cleo needs other people in her life whether she knows it or not. There’s an importance in solititude when she gets to examine the passing world and take in the serenity of running water in a park on a peaceful afternoon. But it’s the people that bring some color to her life. True, she does note that everyone spoils me, no one loves me, undoubtedly bemoaning the quick house call by her lover, the doting of her houskeeper, and the comical buffoonery of her pianist and lyricist duo.

But she also calls on her friend Dorothee who models by day in a sculptor’s studio taking in the bustling Parisian streets with all sorts of people but more importantly time for all sorts of conversation both superficial and sincere. They visit the local cinema and are treated to a silent comedy short (starring Nouvelle Vague power couple Jean-Luc Godard and Anna Karina). As the girl’s boyfriend rightly ascertains comedy is good for the soul. It can help alleviate a world of hurt.

Cleo’s final confidante comes quite by chance. A soldier on leave from Algeria as it turns out. He’s at first forward, then didactic, and finally utterly sincere. He’s perhaps just the type of person Cleo was looking for without even realizing it — someone who is perfectly obliging with conversation when she feels completely taciturn. Theirs is a quick friendship as he agrees to go with her to the hospital for the impending news and she, in turn, looks to see him off to the train station as he goes back from whence he came.

And does the film’s conclusion suffice? Not particularly. It’s abrupt and unsatisfying after all that prolonged wait but curiously Cleo seems at peace. Perhaps that is enough. What this film does impeccably is capture a moment as if it was pure and true and utterly authentic. It takes real world issues and a real world setting, synthesizing them into a fictional storyline that still functions as the every day would.

This is the world of the Cold War, war in Algeria, Edith Piaf in the hospital, Elmer Gantry, Bridget Bardot, and French pop music. It’s all melded together, bits and pieces, and moments and ideas and snapshots into a thoroughly engaging piece that becomes a sort of rumination on life and death and all those things that complicate living. If it all sounds like a jumbled mess of words it is and instead of trying to comprehend it by any amount of diction you should do yourself an immense favor and see Agnes Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7 for yourself. If you are disappointed then I am truly sorry for you. Because it’s a wonderful film.

4.5/5 Stars

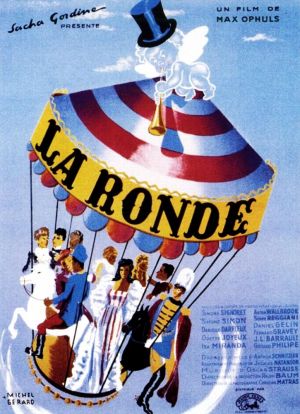

If you know anything about director Max Ophuls you might realize his preoccupation with the cycling of time and storyline, even in visual terms. He initiates La Ronde with a lengthy opening shot that, of course, involves stairs (one of his trademarks), and the introduction of our narrative by a man who sees the world “in the round.” He brings our story to its proceedings, introducing us to the Vienna of 1900. It’s the age of the waltz and love is in the air — making its rounds. It’s meta in nature and a bit pretentious but do we mind this jaunt? Hardly.

If you know anything about director Max Ophuls you might realize his preoccupation with the cycling of time and storyline, even in visual terms. He initiates La Ronde with a lengthy opening shot that, of course, involves stairs (one of his trademarks), and the introduction of our narrative by a man who sees the world “in the round.” He brings our story to its proceedings, introducing us to the Vienna of 1900. It’s the age of the waltz and love is in the air — making its rounds. It’s meta in nature and a bit pretentious but do we mind this jaunt? Hardly. Watching films with French treasure Mr. Hulot (Jacques Tati) is a wonderful experience because, in some respects, it feels like he brings out the child in me. And if history is any indication — I’m not the only one — others feel this sensation too.

Watching films with French treasure Mr. Hulot (Jacques Tati) is a wonderful experience because, in some respects, it feels like he brings out the child in me. And if history is any indication — I’m not the only one — others feel this sensation too. “You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette

“You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively.

Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively. There is no solitude greater than that of the samurai unless it be that of a tiger in the jungle… perhaps…

There is no solitude greater than that of the samurai unless it be that of a tiger in the jungle… perhaps… And though he does call on his lovely girlfriend (Nathalie Delon), who is absolutely devoted to him, as well as making eyes at the nightclub pianist who is the main eyewitness to his hit, Jef for all intent and purposes, is alone. It’s a kind of forced solitude, a self-made exile created by his trade. After he goes through with the hit, he must shut himself off more and more. That is his job.

And though he does call on his lovely girlfriend (Nathalie Delon), who is absolutely devoted to him, as well as making eyes at the nightclub pianist who is the main eyewitness to his hit, Jef for all intent and purposes, is alone. It’s a kind of forced solitude, a self-made exile created by his trade. After he goes through with the hit, he must shut himself off more and more. That is his job. Robert Bresson’s film is an extraordinary, melancholy tale of adolescence and as is his customs he tells his story with an assured, no-frills approach that is nevertheless deeply impactful.

Robert Bresson’s film is an extraordinary, melancholy tale of adolescence and as is his customs he tells his story with an assured, no-frills approach that is nevertheless deeply impactful. Children believe what we tell them. They have complete faith in us. They believe that a rose plucked from a garden can plunge a family into conflict. They believe that the hands of a human beast will smoke when he slays a victim, and that this will cause him shame when a young maiden takes up residence in his home. They believe a thousand other simple things. – Jean Cocteau

Children believe what we tell them. They have complete faith in us. They believe that a rose plucked from a garden can plunge a family into conflict. They believe that the hands of a human beast will smoke when he slays a victim, and that this will cause him shame when a young maiden takes up residence in his home. They believe a thousand other simple things. – Jean Cocteau  One of Jean-Luc Godard’s strengths is his capability of feigning pretentiousness, while still simultaneously articulating humor. His film opens with its first of many inter-titles, “A film adrift in the cosmos,” followed by the equally poignant “A film found in a dump.”

One of Jean-Luc Godard’s strengths is his capability of feigning pretentiousness, while still simultaneously articulating humor. His film opens with its first of many inter-titles, “A film adrift in the cosmos,” followed by the equally poignant “A film found in a dump.” Conflagrations engulf cars and human bodies while above the din comes the piercing screams of a woman bemoaning the loss of her Hermes handbag. We cannot take this anyway but humorous because it once again is yet another moment of utter insanity.

Conflagrations engulf cars and human bodies while above the din comes the piercing screams of a woman bemoaning the loss of her Hermes handbag. We cannot take this anyway but humorous because it once again is yet another moment of utter insanity. It’s only 40 minutes — hardly a feature film and more of a featurette, but Jean Renoir’s truncated work, A Day in the Country, is nonetheless still worth the time. Admittedly, I still have yet to venture to France and I hope to do that someday soon, but this film propagates marvelous visions of the countryside that resonate with all of us no matter where we hail from. Those quiet jaunts out in nature. Sunny days perfectly suited for a lazy afternoon picnic. Peacefully gliding down the river as men fish on the bank contentedly.

It’s only 40 minutes — hardly a feature film and more of a featurette, but Jean Renoir’s truncated work, A Day in the Country, is nonetheless still worth the time. Admittedly, I still have yet to venture to France and I hope to do that someday soon, but this film propagates marvelous visions of the countryside that resonate with all of us no matter where we hail from. Those quiet jaunts out in nature. Sunny days perfectly suited for a lazy afternoon picnic. Peacefully gliding down the river as men fish on the bank contentedly. As always these characters set up Renoir’s juxtaposition of luscious extravagance with the earthier lifestyle of the lower classes. However, there is a geniality pulsing through this film, with Mrs. Dufour exclaiming how polite these young men are–they must be of good stock, obviously not tradesmen. Even Mr. Dufour is a good-natured old boy who gets fed up with the elderly grandmother, but he willingly takes the boys charity and advice when it comes to the prime fishing holes.

As always these characters set up Renoir’s juxtaposition of luscious extravagance with the earthier lifestyle of the lower classes. However, there is a geniality pulsing through this film, with Mrs. Dufour exclaiming how polite these young men are–they must be of good stock, obviously not tradesmen. Even Mr. Dufour is a good-natured old boy who gets fed up with the elderly grandmother, but he willingly takes the boys charity and advice when it comes to the prime fishing holes. We get the essence of what is there and we can still thoroughly enjoy Renoir’s composition. His is a fascination in naturalistic beauty where he nevertheless stages his narrative to unfold in time. But really this mise-en-scene created by the woods, and meadows, trees, and rivers really function as another character altogether. And when all the players interact it truly not only elicits tremendous joy but an appreciation for Renoir’s so-called Poetic Realism. Whether he’s capturing a woman swinging jubilantly on a swing or framing a shot within the trees, we cannot help but tip our hat to his artistic vision. If his father Auguste was one of the great painters of the impressionist era, then Jean was certainly one of the most prodigious filmmakers of his generation, crafting his own pieces of impressionistic realism. In fact, with father and son, you can see exactly how art forms can overlap on canvas and celluloid. They truly share a fascination in some of the same subjects. Universal things like nature and human figures interacting in the expanses of such environments. It’s beautiful really, even in its pure simplicity.

We get the essence of what is there and we can still thoroughly enjoy Renoir’s composition. His is a fascination in naturalistic beauty where he nevertheless stages his narrative to unfold in time. But really this mise-en-scene created by the woods, and meadows, trees, and rivers really function as another character altogether. And when all the players interact it truly not only elicits tremendous joy but an appreciation for Renoir’s so-called Poetic Realism. Whether he’s capturing a woman swinging jubilantly on a swing or framing a shot within the trees, we cannot help but tip our hat to his artistic vision. If his father Auguste was one of the great painters of the impressionist era, then Jean was certainly one of the most prodigious filmmakers of his generation, crafting his own pieces of impressionistic realism. In fact, with father and son, you can see exactly how art forms can overlap on canvas and celluloid. They truly share a fascination in some of the same subjects. Universal things like nature and human figures interacting in the expanses of such environments. It’s beautiful really, even in its pure simplicity.