“Now I only have one thing left to do: Nothing. I don’t want any belongings, any memories. No friends, no love. Those are all traps.”

“Now I only have one thing left to do: Nothing. I don’t want any belongings, any memories. No friends, no love. Those are all traps.”

I once thought that Before Sunrise was the type of movie that I would want to make. Three Colors: Blue is another concept that I have often envisioned without even knowing it. In fact, I had seen The Descendants, a film with a somewhat similar story arc told from a different perspective. Except whereas Clooney’s film is full of blatant drama and intense familial moments in Hawaii, Blue is far more nuanced.

The Descendants might be a more gripping drama, but Blue has the sort of complex depiction that seems to more closely mirror reality. The grieving process involves isolation, solemness, and at times few words. The easiest way to grieve is not to feel, not to fully embrace the pain. Sometimes that is the simplest if not the healthiest way to deal with it for Julie. It’s a real world approach to the scenario, and it’s no less painful to watch — perhaps even more so.

Julie’s husband Patrice de Courcy was a famous composer who was commissioned to arrange a grand piece to be performed at concerts for the Unification of Europe. It is a great honor and we quickly learn that Patrice is quite a big deal. However, after a car accident, Patrice and his 5-year-old daughter perish in the crash and only Julie gets away alive. It is a stark, unsentimental picture, and it succeeds in changing Julie’s life forever.

Julie’s husband Patrice de Courcy was a famous composer who was commissioned to arrange a grand piece to be performed at concerts for the Unification of Europe. It is a great honor and we quickly learn that Patrice is quite a big deal. However, after a car accident, Patrice and his 5-year-old daughter perish in the crash and only Julie gets away alive. It is a stark, unsentimental picture, and it succeeds in changing Julie’s life forever.

After being released from the hospital she soon sells all her possessions and moves out of her family apartment to take up residence somewhere far removed from any acquaintances, including a man named Olivier who is in love with her. She has a new home and begins to sever ties to her old life. The unfinished work of her husband (and her) is trashed and that’s the end of that. In her new Parisian home, she has a rodent problem and becomes the hesitant confidant of a local exotic dancer. Furthermore, she rejects the necklace that a young man pulled out of the wreckage. Her times of solitude are spent swimming laps alone in the local pool, submerged and half-covered in shadow. Grandiose symphonies reverberate through her mind haunting her. In such moments, Kieslowski will often black out the screen in the middle of the scene, effectively interrupting the action for a few seconds before bringing us back.

Words are few and far between for Julie and when she does speak it is often brief and reserved. We are, therefore, forced to observe her without the aid of dialogue. She is certainly detached but there is a provocative side to her. Something is mystifying about her soft features, dark eyes, and short hair. She is a wonderful woman of mystery and beauty because the reality of it is, we do not know a whole lot about her. We must discover more bit by bit and she does not readily disclose information.

It is when pictures of her life literally flash before her eyes on a TV screen that the story takes its next turn. Julie learns soon enough that her husband had a mistress that he was with for a few years. In the hands of Hollywood, this would be high drama. In the hands of Kieslowski, it is far from it. Julie is still the same aloof individual she always was and even a confrontation with the mistress does not change that. She is civil and generous through it all.

It is when pictures of her life literally flash before her eyes on a TV screen that the story takes its next turn. Julie learns soon enough that her husband had a mistress that he was with for a few years. In the hands of Hollywood, this would be high drama. In the hands of Kieslowski, it is far from it. Julie is still the same aloof individual she always was and even a confrontation with the mistress does not change that. She is civil and generous through it all.

Finally, she returns to her husband’s composition which she learns Olivier has started to rewrite. They agree that he will make his own work and Julie must accept it for what it is. Faces from the film float across the screen and a still solemn Julie lets out a few silent tears. The anti-tragedy is complete, a subdued, intriguing piece of cinema. Not for those with short attention spans but, I am interested to see Red and White. Kieslowski intrigues me with his thought provoking films somehow reminiscent of the likes of Bergman or Bunuel.

4.5/5 Stars

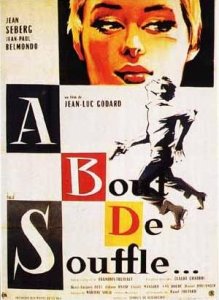

Directed by Jean-Luc Godard, this film follows a young woman who meets two crooks in an English language class. Through narration we learn that she told them about a cache of money she knows of and so they get her to help them swipe it. They both fight for her affection and ultimately the thug Arthur wins out. Despite Odile’s apprehension at taking the money from her aunt’s home, they continue to get the plan ready. Arthur’s uncle now wants in and then the plan changes again because the owner of the money is gone a day earlier. From this point everything begins to go wrong and after a horrible botched attempt the three culprits flee the scene with little to show for their caper. Arthur makes up an excuse to return and Odile and Franz drive off but they return when trouble seems imminent. Back at the house Arthur is confronted by his uncle and there is more bloodshed. Afterwards Odile and Franz again flee heading to South America while the narrator promises a sequel in the near future. This film unabashedly proclaims to be Nouvelle wave even going so far as having it printed on a store banner. Again, Godard combines his love of American pulp fiction and artistic experimentation to create yet another tragic tale. The film gives a nod to Hollywood crime films and also features several famous sequences. Some high points include the moment of silence, the spontaneous dance in the café, and of course the run through the Louvre. In my mind, Pulp Fiction owes at least something to Godard right here.

Directed by Jean-Luc Godard, this film follows a young woman who meets two crooks in an English language class. Through narration we learn that she told them about a cache of money she knows of and so they get her to help them swipe it. They both fight for her affection and ultimately the thug Arthur wins out. Despite Odile’s apprehension at taking the money from her aunt’s home, they continue to get the plan ready. Arthur’s uncle now wants in and then the plan changes again because the owner of the money is gone a day earlier. From this point everything begins to go wrong and after a horrible botched attempt the three culprits flee the scene with little to show for their caper. Arthur makes up an excuse to return and Odile and Franz drive off but they return when trouble seems imminent. Back at the house Arthur is confronted by his uncle and there is more bloodshed. Afterwards Odile and Franz again flee heading to South America while the narrator promises a sequel in the near future. This film unabashedly proclaims to be Nouvelle wave even going so far as having it printed on a store banner. Again, Godard combines his love of American pulp fiction and artistic experimentation to create yet another tragic tale. The film gives a nod to Hollywood crime films and also features several famous sequences. Some high points include the moment of silence, the spontaneous dance in the café, and of course the run through the Louvre. In my mind, Pulp Fiction owes at least something to Godard right here.