Here is a tale of Tin Pan Alley and the ensuing partnership of real-life songwriting duo Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby. The cast was what had me deeply intrigued because, in this day and age, my only connection to the two songsmiths is “I Wanna Be Loved by You,” memorably performed by Marilyn Monroe in Some Like it Hot (1959). In this film, it’s given a cutesy performance by an up-and-comer named Debbie Reynolds.

However, that’s not much of a background to go off of, but boy, do I enjoy Fred Astaire and Vera-Ellen. Having them together is a tantalizing proposition indeed. Red Skelton always struck me more as a mainstay of Ed Sullivan Show reruns than an actor and Arlene Dahl was a relatively recent discovery. Still, each performer contributes to the overwhelming appeal.

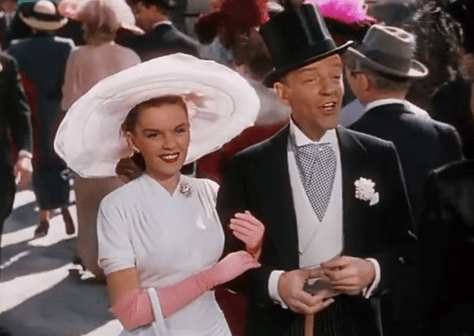

Three Little Words immediately introduces an opening number with Astaire and Vera-Ellen which starts things off on the right foot with its toe-tapping assets. They are a close-knit song-and-dance pair with talk floating between them about getting married. She’s in love with him. He’s in love with her…and his work.

Their next performance of “Mr. and Mrs. Hoofer at Home” might be the film’s finest hour as far as the dance numbers go, showcasing the technical expertise of its stars who make it look delightfully effortless. I could not help recalling first Keaton’s One Week (1920) and then a bit of Chaplin from Modern Times (1936) in his dream house with Paulette Goddard.

Because here we have the continuation of the same motif as articulated this time around by Astaire and Vera-Ellen. The novelty is taking something so integral to American life, that is the home, gender roles, and the cult of domesticity as it were, and personifying it visually through metaphor and movement. It works wonders in such a colorfully abstract space.

It’s no coincidence that Keaton and Chaplin were comics of a very physical nature. Likewise, the dance of Astaire with his leading lady is equally silly, in a sense, but also so very inventive in how it expresses the mundane rhythms of life many of us experience every day. It’s my favorite out-and-out moment in the picture.

Because I’ve always maintained a fairly conflicted relationship with musical biopics. The prime example might be Yankee Doodle Dandy, which has spectacular moments thanks to the indelible James Cagney, but it also comes off rather flat and insipid in other patches. The agenda is complicated by the fact that we are taking a real person’s life and trying to dress it up. We can hardly look at it like fact and yet we are often dealing with real names and real places. It’s this odd brand of authenticity that feels sanitized and in some ways totally fake.

But if we take it for what it is, enjoy the dance numbers, and disregard the dubious guises that men like Astaire and Red Skelton are putting on, it’s easy enough to enjoy their charms. There are glimpses of how the musical creative process works and a vaudeville nostalgia wafts over the picture, which no doubt endeared Astaire to the project. One slight nod I picked up on was Gloria De Haven playing a character (I think) named after her father, Carter De Haven, though her mother was on the Vaudeville circuit as well.

It’s a fluke knee injury that finally leads to the unlikely pairing of our two down-and-outers. It begins down a contentious road and never quite rights itself, but along the way, they crank out such well-received hits as “My Sunny Tennessee” and “So Long Oolong” both unquestionably catchy.

You begin to understand more deeply the culture of the time when every family had a piano in the living room to gather around and radio had yet to take over the country. In such a period, sheet music and tunes crafted by the likes of Kalmar and Ruby were all the rage.

Because they could be reprinted and replayed time and time again. Thus, it wasn’t so much about the artist, unless you had the good fortune (and the money) to see them live. It was about the writers and lyricists who could pen catchy tunes agreeable to a wide audience. That was the way the industry went. We were a long way off from rockability, disc jockeys, and record sales.

While Kalmar finally gets it into his skull to marry Jessie thanks to her prodding, Ruby continues to pick the wrong girls, starting with a flirty nightclub dancer (Gale Robbins) who has about a million beaus at her disposal. His friends watch out for his interests, and he ultimately winds up with a beautiful actress (Dahl as the real-life Eileen Percy), under hilarious circumstances. She’s a big deal now, but Ruby doesn’t remember that they’ve met before…

The creative output continues in spurts from more songs, then distractions, then Animal Crackers with the Marx Brothers, and more songs. Ultimately, a spat breaks up the partnership for what seems like the last time. Though Ruby is now married and equally happy, the wives know their men need to get back together.

With a certain amount of forethought, both missuses strike up a reunion between their husbands by giving them a bit of a helpful push instigated by Phil Regan’s popular radio show. In one regard, nothing has changed. They’re still as ornery as ever, but they retain that same glimpse of brilliance — smiles breaking over their faces one last time.

Three Little Words was probably more true to life than some biopics of its day and amid what is dressed up or relatively accurate, the most interesting ideas on the table have to do with the creative collaboration between two men. It’s true that in such instances, opposites attract. One is usually musically-inspired, coming up with tunes just like that, and the other able to tinker with words to make them fit perfectly with a melody. On their own, they would be nowhere, and yet together, they’re able to literally create music to our ears.

But the other side of such a partnership is the invariable disagreements that arise. There’s the inevitable conflict that comes from two personalities with personal vision and diverging personalities. The most iconic examples I always go back to were The Beatles because by the end you had three leads with John and Paul and George. Although Harrison was the third-fiddle, after the breakup, he would release arguably the greatest album of any of their solo careers: All Things Must Past.

However, sometimes there’s also a lack of interest and then a desire for a change of pace. In this story, Bert is obsessed with being a magician and even tries his hand at playwriting. Meanwhile, Harry has always held onto the aspirations of being a big-league ballplayer. The real miracle is that they stayed together for so long, crafting such a bevy of classics.

3.5/5 Stars