Anyone who takes the time to search out this movie whether the reason is a young Jack Nicholson who wrote, helped finance, and starred in this western or because it’s directed by cult favorite Monte Hellman, they probably already know it was shot consecutively with The Shooting. Whereas the first western has an unnerving existential tilt as the plot takes us through an endless journey across the oppressive desert plains, you could make the claim that Ride in the Whirlwind is a more conventional western.

Anyone who takes the time to search out this movie whether the reason is a young Jack Nicholson who wrote, helped finance, and starred in this western or because it’s directed by cult favorite Monte Hellman, they probably already know it was shot consecutively with The Shooting. Whereas the first western has an unnerving existential tilt as the plot takes us through an endless journey across the oppressive desert plains, you could make the claim that Ride in the Whirlwind is a more conventional western.

However, it’s still highly intriguing for its main premise and the dilemmas that evolve as a result. But that’s enough with the big picture. Here are a few more details to fill in between the lines. The action begins with a holdup, a true western staple. True, a pair of men get injured but it’s about what you expect from such a skirmish. In the end, the stage rides off generally unimpeded and the bandits retreat to their lair up in the nearby mountains to wait it out for a while. Maybe they know a posse is on their trail and maybe not.

Either way, they’re mighty careful when a trio of riders make their way through the main pass. Of course, they don’t know that these are only a few cowhands making their way to Texas and they’re looking for a place to bed down for the night.

Both sides have a general sense of the other but rather than make waves they do the mutually beneficial thing and everything goes about their business nice and easy. There’s no need for guns and no ones looking for any trouble.

But the next morning a posse that means business rolls in and they’re not about to wait and ask questions. They set up posts to pin down their adversary and they hardly discriminate between who was a bandit and who is innocent. That’s not the way their righteous form of justice works.

Rather like the early Hollywood Classic The Ox-Bow Incident, they are searching for the men to lynch and it hardly seems to make any difference if the men are innocent or not. They shall be avenged. However, an interesting observation is that in once sense this does not seem like mob rule. The posse is calculated and cool in executing their objective although that’s no comfort to those who are actually innocent.

In the ensuing standoff, one of the ranch hands, caught in the crossfire gets it and the two bandits who come out with their lives get about what we expect. The second half of the film follows the two men who were able to escape and they just want to find a pair of horses so they can ride away from the whole business.

Their quest on foot leads them to a nearby homestead and this latter half of the story brings to mind earlier pictures such as Shane or Hondo where families are seen trying to make a life for themselves out on the plains.

Wes (Nicholson) and Vern (Cameron Mitchell) are desperate to get away yes, and they sneak into the families home but what makes them so different is the very fact that they are not real criminals. They are only doing this out of necessity. They treat the womenfolk respectfully including the ranchers taciturn daughter Abigail (Millie Perkins) but they’re also bent on taking for themselves a pair of horses.

First off, Evan ain’t so keen on having his home invaded or his family held hostage and he’s especially not obliging that they’re going to run off with some of his stock because they’re his after all.

This is in itself another brooding film like The Shooting but for different reasons. It’s filled with genuine tension because the irony of the situation is that we know these men are innocent and yet in order to survive in some ways they must take on the mantle of criminals just to live another day. There’s no space for a rational third way. There’s no grace or any type of understanding and so they’re forced to play by the rules already set up by the posse that’s pursuing them. That’s the moral conundrum at the core of this tale.

Ride in the Whirlwind has the dismal type of ending we expect with a bit of a silver lining but it’s that very shred of hope that makes it an affecting western. It feels right at home with the sentiments of the 1960s where the world is not as innocent as it used to be and the world often does not function by the most equitable standards. Some would say that’s why the western fell out of favor because in the classical sense, it no longer reflected the perceived world at large like it once did.

3.5/5 Stars

Crime films, westerns, and horror. It’s easy to see why these genres make arguably the best B-pictures, all things considered. It lies in their ability to deliver thrills with minimal capital and a bit of inspiration. Film Noir is by far my favorite but a film such as The Shooting makes me love shoestring westerns too. Except that’s just an initial gut reaction. What happens over the course of this film truly plays with our preconceptions. Its ambitions being rather curious.

Crime films, westerns, and horror. It’s easy to see why these genres make arguably the best B-pictures, all things considered. It lies in their ability to deliver thrills with minimal capital and a bit of inspiration. Film Noir is by far my favorite but a film such as The Shooting makes me love shoestring westerns too. Except that’s just an initial gut reaction. What happens over the course of this film truly plays with our preconceptions. Its ambitions being rather curious. Destry Rides Again is integral to the tradition of comedy westerns–a storied lineage that includes the likes of Way Out West, Blazing Saddles, and Support Your Local Sheriff. It takes a bit of the long maintained western lore and gives it a screwy comic twist courtesy of classic Hollywood.

Destry Rides Again is integral to the tradition of comedy westerns–a storied lineage that includes the likes of Way Out West, Blazing Saddles, and Support Your Local Sheriff. It takes a bit of the long maintained western lore and gives it a screwy comic twist courtesy of classic Hollywood. When put up against more sophisticated brands of humor and satirical wit, it would be easy to call the likes of Laurel & Hardy the lowest form of comedy. It sounds degrading but it’s also quite true. Their pictures are short. They’re for all intent and purposes plotless aside from one broad overarching objective. Their gags are simple. Pratfalls. Mannerism. Foibles. Visual gimmicks. More pratfalls and mayhem. It’s not brain science. It’s not reinventing the wheel. So, yes, it might be the simplest brand of comedy but it also might just be the funniest and most universal comedy out there.

When put up against more sophisticated brands of humor and satirical wit, it would be easy to call the likes of Laurel & Hardy the lowest form of comedy. It sounds degrading but it’s also quite true. Their pictures are short. They’re for all intent and purposes plotless aside from one broad overarching objective. Their gags are simple. Pratfalls. Mannerism. Foibles. Visual gimmicks. More pratfalls and mayhem. It’s not brain science. It’s not reinventing the wheel. So, yes, it might be the simplest brand of comedy but it also might just be the funniest and most universal comedy out there. Though it’s easy to be a proponent of

Though it’s easy to be a proponent of

It’s hard to grow tired of Bob Hope. In many ways, he’s a universal entertainer — transcending time — circumventing the decades with a brand of humor that is timeless. And the same goes for his iconic persona. He can quip with his lips like Groucho Marx but he’s more of a lovable dope. He likes to think he’s clever and when he lets his mouth run off Hope certainly is, in a cheeky sort of way. It’s just his characters who are always dumb.

It’s hard to grow tired of Bob Hope. In many ways, he’s a universal entertainer — transcending time — circumventing the decades with a brand of humor that is timeless. And the same goes for his iconic persona. He can quip with his lips like Groucho Marx but he’s more of a lovable dope. He likes to think he’s clever and when he lets his mouth run off Hope certainly is, in a cheeky sort of way. It’s just his characters who are always dumb. “Ringo don’t look so tough to me.”

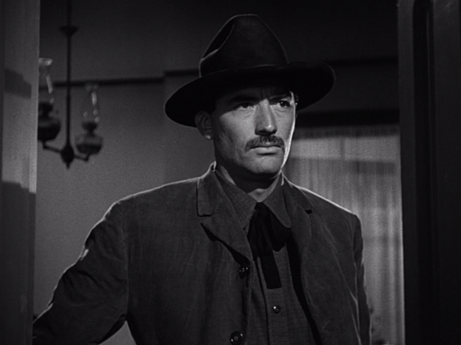

“Ringo don’t look so tough to me.” Of all men to understand Ringo, you would think that the local Marshall (Millard Mitchell) would be the last, but he happens to be an old friend of the gunman. They used to run in the same circles before Mark softened up. His life mellowed out, while Ringo’s reputation continued to build.

Of all men to understand Ringo, you would think that the local Marshall (Millard Mitchell) would be the last, but he happens to be an old friend of the gunman. They used to run in the same circles before Mark softened up. His life mellowed out, while Ringo’s reputation continued to build. The main reason Ringo stays in a town that doesn’t want him is all because of a girl (Helen Westcott). He waits and waits, biding his time, for any word from her, and finally, it comes. He gets his wish to see her and his son in private. These scenes behind closed doors are surprisingly intimate, casting the old gunman in an utterly different light.

The main reason Ringo stays in a town that doesn’t want him is all because of a girl (Helen Westcott). He waits and waits, biding his time, for any word from her, and finally, it comes. He gets his wish to see her and his son in private. These scenes behind closed doors are surprisingly intimate, casting the old gunman in an utterly different light.