Coming out of a psychology background I was familiar with Stanley Milgram’s famous social experiment back in high school during Intro to Psych. Even back then it was a striking conclusion on conformity and just how far people will go. It was also ruthlessly contrived and even more methodically executed. Inspiration came from Milgram’s own background working with psychologist Solomon Asch, as well as his own Jewish ancestry, nights watching Candid Camera, and a fascination in the Adolf Eichmann trial.

Coming out of a psychology background I was familiar with Stanley Milgram’s famous social experiment back in high school during Intro to Psych. Even back then it was a striking conclusion on conformity and just how far people will go. It was also ruthlessly contrived and even more methodically executed. Inspiration came from Milgram’s own background working with psychologist Solomon Asch, as well as his own Jewish ancestry, nights watching Candid Camera, and a fascination in the Adolf Eichmann trial.

The results of his controversial deception are staggering. If people are told to administer an electric shock, even against their own will, knowing that the other person might full well be hurt, they will comply with benevolent authority. When you think about its moral implications, you wonder why no one had yet to make a film about it, but then again, now someone has.

Michael Almereyda appears to be the heart and soul of this film, and he brings together a mixed bag of talent, headed by Alexander Skarsgard and Winona Ryder, with various supporting spots filled by the likes of Jim Gaffigan, John Leguizamo, Anton Yelchin, Dennis Haysbert, and Anthony Edwards.

This is a stripped down film of simple design, but it rocks us with potency because its basic premise is so intriguing. It’s difficult not to be fascinated by the findings of Milgram since they feel as startling now as they were back in 1962. The scary part is that humanity has not changed all that much, not really when we get down to the base levels of human nature.

It puts the systematic genocide of the Nazis into perspective, but it has even more frightening implications for all of humanity. It leads to soul-searching, personal reconciliation, and of course, backlash, against Milgram himself. As the moral issues are twofold. The participants subjected to such an illusion, with confederates playing along, are forced to figure out their own conscience — what this all means about them. Meanwhile, the man behind this deception is understandably under fire. The public cannot fully condone what they did, nor do they want to believe his results.

Milgrim would lose his tenure, but as the years rolled ever onward, he carved at a decent life for himself with his wife, kids, and a nice work circuit, giving lectures and continuing his social experiments on conformity.

These are the fascinating aspects of the film. It’s when it gets a tad pretentious, breaking the fourth wall and using obviously phony back projection to tell the story of Milgram the man, that it ceases being as interesting. Because we are intrigued far more by his work than him as a person. He’s hardly an anomaly and more the norm, so we begin to remember why a film was never made about him before. The narrative strands start becoming fairly thin.

But in some ways, Experimenter feels like an apt companion piece to the film Hannah Arendt, because they both examine two people fascinated with human kind’s capacity to commit evil by examining not simply Adolf Eichmann but a great many other everyday individuals. That alone makes it worthwhile viewing — especially those fascinated by psychology. Like the former film, it’s hardly perfect or even cutting edge when it comes to biopics, but it certainly gives the viewer something to grapple with.

3.5/5 Stars

“Two people shouldn’t know each other too well if they want to fall in love. But, then, maybe they shouldn’t fall in love at all.” – Vittoria

“Two people shouldn’t know each other too well if they want to fall in love. But, then, maybe they shouldn’t fall in love at all.” – Vittoria The initial scene in the stock exchange is gloriously tumultuous and it never lets up. This is the dashing young Piero’s (Alain Delon) domain that he rushes through with lithe business savvy. What this arena becomes is the quintessential Italian marketplace, a hectic theater of business made up of all kinds, involved parties and observers alike. Vittoria (Vitti) is one of those who looks on with mild interest and really throughout the entire film she is a keen observer as much as she is a person of action.

The initial scene in the stock exchange is gloriously tumultuous and it never lets up. This is the dashing young Piero’s (Alain Delon) domain that he rushes through with lithe business savvy. What this arena becomes is the quintessential Italian marketplace, a hectic theater of business made up of all kinds, involved parties and observers alike. Vittoria (Vitti) is one of those who looks on with mild interest and really throughout the entire film she is a keen observer as much as she is a person of action. And the narrative becomes perhaps even more tantalizing than love because it’s the prospect of romance that keeps it going. But it never seems fully realized. It’s frustrating, unfulfilling in a sense, like most of his films. Whether it’s an unsolved mystery or the most perplexing conundrum mankind has ever faced romantic attraction, he always leaves us an open-ended denouement.

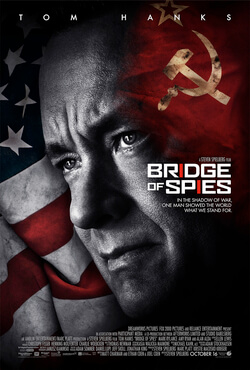

And the narrative becomes perhaps even more tantalizing than love because it’s the prospect of romance that keeps it going. But it never seems fully realized. It’s frustrating, unfulfilling in a sense, like most of his films. Whether it’s an unsolved mystery or the most perplexing conundrum mankind has ever faced romantic attraction, he always leaves us an open-ended denouement. Steven Spielberg is this generation’s

Steven Spielberg is this generation’s

Arguably the greatest French comic was Jacques Tati and like Chaplin or Keaton he seemed to have an impeccable handle on physical comedy, combining the human body with the visual landscape to develop truly wonderful bits of humor. Bed and Board is a hardly a comparable film, but it pays some homage to the likes of Mon Oncle and Playtime. There’s a Hulot doppelganger at the train station, while Antoine also ends up getting hired by an American Hydraulics company led by a loud-mouthed American (Billy Kearns) who closely resembles one of Hulot’s pals from Playtime. Furthermore, there are supporting cast members with a plethora of comic quirks. The man who won’t leave his second story apartment until Petain is dead and buried at Verdun. No one seems to have told him that the old warhorse has been dead nearly 20 years. The couple next door that is constantly running late, the husband pacing in the hallway as his wife rushes to make it to his opera in time. There’s the local strangler who is kept at arm’s length until the locals learn something about him. The rest is a smattering of characters who pop up here and there at no particular moment. Their purpose is anyone’s guess, and yet they certainly do entertain.

Arguably the greatest French comic was Jacques Tati and like Chaplin or Keaton he seemed to have an impeccable handle on physical comedy, combining the human body with the visual landscape to develop truly wonderful bits of humor. Bed and Board is a hardly a comparable film, but it pays some homage to the likes of Mon Oncle and Playtime. There’s a Hulot doppelganger at the train station, while Antoine also ends up getting hired by an American Hydraulics company led by a loud-mouthed American (Billy Kearns) who closely resembles one of Hulot’s pals from Playtime. Furthermore, there are supporting cast members with a plethora of comic quirks. The man who won’t leave his second story apartment until Petain is dead and buried at Verdun. No one seems to have told him that the old warhorse has been dead nearly 20 years. The couple next door that is constantly running late, the husband pacing in the hallway as his wife rushes to make it to his opera in time. There’s the local strangler who is kept at arm’s length until the locals learn something about him. The rest is a smattering of characters who pop up here and there at no particular moment. Their purpose is anyone’s guess, and yet they certainly do entertain. But as Truffaut usually does, he digs into his character’s flaws that suspiciously look like they might be his own. Antoine easily gets swayed by the demure attractiveness of a Japanese beauty (Hiroko Berghauer), and he begins spending more time with her. Thus the marital turbulence sets in thanks in part to Antoine’s needless infidelity –revealed to Christine through a troubling bouquet of flowers. It’s hard to keep up pretenses when the parent’s come over again and Doinel even ends up calling on a prostitute one more. It’s as if he always reverts back to the same self-destructive habits. He never quite learns.

But as Truffaut usually does, he digs into his character’s flaws that suspiciously look like they might be his own. Antoine easily gets swayed by the demure attractiveness of a Japanese beauty (Hiroko Berghauer), and he begins spending more time with her. Thus the marital turbulence sets in thanks in part to Antoine’s needless infidelity –revealed to Christine through a troubling bouquet of flowers. It’s hard to keep up pretenses when the parent’s come over again and Doinel even ends up calling on a prostitute one more. It’s as if he always reverts back to the same self-destructive habits. He never quite learns. If you’ve read any of my reviews on the original trilogy, you undoubtedly know that Star Wars had a tremendous impact on my childhood. That’s true for many young boys. It was the film franchise of choice, and it wasn’t just a series of movies. The beauty of Star Wars is that it encompasses an entire galaxy of dreams beyond our own. It’s a world that reflects ours in many ways — the difference is that they have lightsabers. But not just lightsabers. Aliens. Spaceships. Planets. The Force. Characters who for all intent and purposes live like us. Good, that is in constant conflict with the evil in the world. It’s a struggle that is constantly evolving.

If you’ve read any of my reviews on the original trilogy, you undoubtedly know that Star Wars had a tremendous impact on my childhood. That’s true for many young boys. It was the film franchise of choice, and it wasn’t just a series of movies. The beauty of Star Wars is that it encompasses an entire galaxy of dreams beyond our own. It’s a world that reflects ours in many ways — the difference is that they have lightsabers. But not just lightsabers. Aliens. Spaceships. Planets. The Force. Characters who for all intent and purposes live like us. Good, that is in constant conflict with the evil in the world. It’s a struggle that is constantly evolving. Charles Trenet’s airy melody “I Wish You Love” is our romantic introduction into this comedy-drama. However, amid the constant humorous touches of Truffaut’s film, he makes light of youthful visions of romance, while simultaneously reveling in them. Because there is something about being young that is truly extraordinary. The continued saga of Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel is a perfect place to examine this beautiful conundrum.

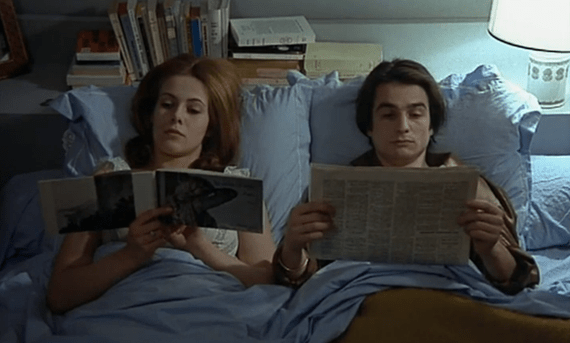

Charles Trenet’s airy melody “I Wish You Love” is our romantic introduction into this comedy-drama. However, amid the constant humorous touches of Truffaut’s film, he makes light of youthful visions of romance, while simultaneously reveling in them. Because there is something about being young that is truly extraordinary. The continued saga of Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel is a perfect place to examine this beautiful conundrum. In fact, all in all, if we look at Doinel he doesn’t seem like much. He’s out of the army, obsessed with sex, can’t do anything, and really is a jerk sometimes. Still, he manages to maintain an amicable relationship with the parents of the innocent, wide-eyed beauty Christine (Claude Jade in her spectacular debut). Theirs is an interesting relationship full of turbulence. We don’t know the whole story, but they’ve had a past, and it’s ambiguous whether or not they really are a couple. They’re in the “friend zone” most of the film and really never spend any significant scenes together. Doinel is either busy tailing some arbitrary individual or fleeing pell-mell from the bosses wife who he has a crush on.

In fact, all in all, if we look at Doinel he doesn’t seem like much. He’s out of the army, obsessed with sex, can’t do anything, and really is a jerk sometimes. Still, he manages to maintain an amicable relationship with the parents of the innocent, wide-eyed beauty Christine (Claude Jade in her spectacular debut). Theirs is an interesting relationship full of turbulence. We don’t know the whole story, but they’ve had a past, and it’s ambiguous whether or not they really are a couple. They’re in the “friend zone” most of the film and really never spend any significant scenes together. Doinel is either busy tailing some arbitrary individual or fleeing pell-mell from the bosses wife who he has a crush on. By the time he’s given up the shoe trade and taken up tv repair he’s already visited another hooker, but Christine isn’t done with him yet. She sets up the perfect meet-cute and the two young lovers finally have the type of connection that we have been expecting. When we look at them in this light, sitting at breakfast, or on a bench, or walking in the park they really do seem made for each other. Their height perfectly suited. Her face glowing with joy, his innately serious. Their steps in pleasant cadence with each other. The hesitant gazes of puppy love.

By the time he’s given up the shoe trade and taken up tv repair he’s already visited another hooker, but Christine isn’t done with him yet. She sets up the perfect meet-cute and the two young lovers finally have the type of connection that we have been expecting. When we look at them in this light, sitting at breakfast, or on a bench, or walking in the park they really do seem made for each other. Their height perfectly suited. Her face glowing with joy, his innately serious. Their steps in pleasant cadence with each other. The hesitant gazes of puppy love. While

While  Whereas the previous Torn Curtain was generally concerned with life behind the Iron Curtain, Topaz is decidedly more continental moving swiftly between Russia, France, America, Cuba, including a few pitstops at international embassies. However, the film does end up spending a lot of time focused on Cuba which can very easily be juxtaposed with the East German scenes in the former film. Hitchcock once more creates an illusion of reality using the Universal backlot and the adjoining area to craft Cuba, and he makes into a place of sunshine and romantic verandas, but it also runs rampant with totalitarian militia. It’s perhaps more exotic and welcoming than East Germany, but no less repressed. In both cases, they become a perilous locale for our protagonists. Still, rather unlike the previous film, Topaz lacks a truly A-list star like Paul Newman or Julie Andrews.

Whereas the previous Torn Curtain was generally concerned with life behind the Iron Curtain, Topaz is decidedly more continental moving swiftly between Russia, France, America, Cuba, including a few pitstops at international embassies. However, the film does end up spending a lot of time focused on Cuba which can very easily be juxtaposed with the East German scenes in the former film. Hitchcock once more creates an illusion of reality using the Universal backlot and the adjoining area to craft Cuba, and he makes into a place of sunshine and romantic verandas, but it also runs rampant with totalitarian militia. It’s perhaps more exotic and welcoming than East Germany, but no less repressed. In both cases, they become a perilous locale for our protagonists. Still, rather unlike the previous film, Topaz lacks a truly A-list star like Paul Newman or Julie Andrews. Torn Curtain was

Torn Curtain was  However, when you watch any Hitchcock film you do wait to be dazzled with some twist or trick because he was always one to bring humor and fascinating aesthetic qualities into his films. Torn Curtain has a few such moments that quickly come to mind. The most prominent has to do with the editing of the sequence in the farmhouse. It is here where Gromek is murdered by Armstrong and the housewife, but it is cut in such a fascinating way. It contrasts with Psycho’s shower sequence quite easily as they try and murder him first by strangling and then anything they can get a hold of whether it’s guns, knives, shovels. There is no score to speak of. Soon it becomes a methodical rhythm of cutting between contorted faces as they slowly but surely move towards the stove. The brutality and length of the ordeal suggest how ugly and laborious it is to kill a man. Hitchcock certainly does not glorify it in any sense.

However, when you watch any Hitchcock film you do wait to be dazzled with some twist or trick because he was always one to bring humor and fascinating aesthetic qualities into his films. Torn Curtain has a few such moments that quickly come to mind. The most prominent has to do with the editing of the sequence in the farmhouse. It is here where Gromek is murdered by Armstrong and the housewife, but it is cut in such a fascinating way. It contrasts with Psycho’s shower sequence quite easily as they try and murder him first by strangling and then anything they can get a hold of whether it’s guns, knives, shovels. There is no score to speak of. Soon it becomes a methodical rhythm of cutting between contorted faces as they slowly but surely move towards the stove. The brutality and length of the ordeal suggest how ugly and laborious it is to kill a man. Hitchcock certainly does not glorify it in any sense. The term “banality of evil” has floated through the lexicon ever since German philosopher and columnist Hannah Arendt coined the phrase during the Eichmann trial back in 1961. In fact, the words gained so much traction that they have undoubtedly lost some impact due to overuse. However, this film takes equal interest in the backlash that she received on her remarks about the Jewish community. Her claim that the Jews were collaborators with the Nazis and privy to their own destruction, undoubtedly would be unpopular now. Back then it was a pure lightning rod for scurrilous criticism and hateful backlash.

The term “banality of evil” has floated through the lexicon ever since German philosopher and columnist Hannah Arendt coined the phrase during the Eichmann trial back in 1961. In fact, the words gained so much traction that they have undoubtedly lost some impact due to overuse. However, this film takes equal interest in the backlash that she received on her remarks about the Jewish community. Her claim that the Jews were collaborators with the Nazis and privy to their own destruction, undoubtedly would be unpopular now. Back then it was a pure lightning rod for scurrilous criticism and hateful backlash.