Here is the first of two purported instances where Paul Newman wound up taking on roles earmarked for the recently deceased James Dean. Dean even had a fairly visible relationship with Pier Angeli who would have been his co-star. At one point, there was even talk of marriage swirling around though Angeli’s mother disapproved of Dean. Because it’s true he was “the rebel,” and she the angelic ingenue. It served them both well on screen, and the saintly image works well opposite Newman here.

While Dean had the angst and a sturdy enough frame to have at Rock Hudson in Giant, there’s no doubt his slight build doesn’t seem like the physique of a boxer. In this physical regard alone Newman might have proved to be a fine choice and in consideration of the performance itself, he showcases a glint of many of the traits that would turn him into a beloved box office attraction.

Watching his big break in the context of his illustrious career is gratifying for just those reasons. Because we know the successes waiting for him. Somebody Up There Likes Me finally gave him a shot to put himself out there so people could take note.

Due to the aura of The Sound of Music and to a lesser extent West Side Story, they are two films that effectively misrepresent the career of director Robert Wise. At the very least, they can be deceptive.

True, West Side Story gives us a glimpse into gangland New York, albeit touched up in vibrant color. But we only need look to Wise’s early noir works, a pedigree including the boxing classic The Set-Up; or even Odds Against Tomorrow, to see what he was capable of in terms of grungy atmospherics. This one occupies a seedy dive world akin to something like On The Waterfront (1954) or even Love with a Proper Stranger (1963).

Coincidentally, Steve McQueen has an early part in this one and Sal Mineo, a Dean compatriot leftover from Rebel Without a Cause, gives a crucial supporting role. Because Rocky incurs a childhood of abuse only to grow up as a hoodlum on the streets terrorizing the neighborhood with his band of cronies. Romolo (Sal Mineo) is the most important because they have the same life experience but wind up in completely different stratospheres.

It does take Rocky a long time though. He lands himself in a reformatory and gets thrown around the social reform structures implemented by society, all to no avail. He gets upgraded to a Penitentiary and still, his brutish intensity is never cowed.

Picking a fight with everyone big or small. It doesn’t matter if they’ve got stripes on their shoulders, suits, college educations, or police badges in their pockets. He’s ready and willing to wail on anyone. To say he has a blatant disregard for rules and authority is a gross understatement. It’s part of what makes Newman’s turn entertaining in the earliest segments.

We wonder when he’s ever going to hit an upswing as he’s on the lamb, then dishonorably discharged, and awarded a stint at Leavenworth. Could that be a bit of Luke Jackson that we see?

Even as he reluctantly agrees to jump in the ring for a promoter (Everett Sloane) to earn some desperately needed cash, he never has a taste for fighting. It seems like for once in his life the newly minted Rocky Graziano (like the wine) is looking to get away from fighting. And yet over time, he is convinced to train and to channel his hate into his right hand, like a charge of dynamite, so it can benefit him in the confines of the ring.

Also, about this time, he is introduced to his sister’s friend Norma, a sweet, reticent girl who is taken with romantic movies, butterfly kisses, and nice words spoken out of a place of kindness. Rocky’s entire upbringing has left him with the impression “love is for the birds.” They shouldn’t be together and yet, for some unexplainable reason, they are.

Soon, with the help of Irving (Sloane), Rocky has made a name for himself as the most popular Italian in the world, aside from Frank Sinatra and Michelangelo. Still, Norma can’t stand his fighting believing it is all, “meanness and blood and ignorance.”

On the surface, it seems true. However, Graziano is a curious force. So brutal and antagonistic and yet in his own gruff way, he’s so capable of love. He loves his mother (Eileen Heckert) dearly even as he tears her apart. He loves his wife, never laying a hand on her. He only has tenderness in his heart for them.

Still, in the ring he is ruthless and outside it, he’s plagued by fixers (Robert Loggia in a slimy debut) and a horde of journalists looking to smear his past all over the tabloids.

The climactic bout versus incumbent champion Tony Zale personifies how chaotically communal boxing is. An assortment of POV shots with punches aimed right at the camera, a flurry of edits, and a boisterous brand of intimacy makes us feel like we’re living right inside the ring. The beauty of it has to be the fact Rocky seems like he’s losing the entire time. Sometimes that doesn’t matter. Grit alone sustains. It’s a delightful finishing point, but the film is not won in the ring.

I’m trying to come up with concrete justifications for why I enjoyed this experience so much. A few have been offered up but on the whole, I’m at a loss for words. Certainly Wise is no stranger to this street corner aesthetic, which he develops with such assured conviction, but the beats of the story are nothing new. They come to be expected; what takes you by pleasant surprise in such a context is a performance or a bit of dialogue from Ernest Lehman.

Because the boxing ring is only ever an arena for the life outside the ropes to play out and thankfully a rapport is built with the characters that comes to more than a few fights to prove oneself. In fact, until the final showdown in the ring, most of what we know about Rocky occurs outside of the ring with the gloves off.

Newman invests himself in the part readily showing a young punk evolve into a broken man with hatred in his blood, delinquency, and rage at the core of his being. Yet by some miracle, he’s able to gain a life and a beautiful girl to bless him with an existence worth living. Yes, he wins a big fight in the end, but we get the sense we leave him on a firm foundation. When the inevitable comes and he’s taken down, there’s still something and someone to return home to. Until that day he can relish what he was bred to do. But it’s not his all.

Then, of course, there’s Pier Angeli who is a minor revelation not because of any amount of flamboyance but the exact opposite. She is gifted with a grace and a poise that is positively enthralling. Her voice, quiet even hushed, flows with a peacefulness — an unassuming dignity even — so very unlike the ravishing vivacity of our Italian movie star archetypes. She is a discovery to be sure though her life was unfortunately cut tragically short. This role might be the finest testament to her presence as a performer.

It’s admittedly almost hokey witnessing Rocky riding down a cheering street, staring into the heavens noting exuberantly, “Somebody up there likes me.” Certainly, that’s true, but his wife reminds him, “Someone down here does too.” That’s how he knows The Big Man Upstairs was looking after him, putting such a calming force into the turbulence of his own life. The scene is so easy to forgive because we’ve witnessed how very true it is.

This boxing biopic would be something of lesser note without Paul Newman’s star-making turn and what is an anti-hero without a companion to salvage their brokenness and turn them into the best person that they can be? Accordingly, comparable praise must be heaped on Angeli too.

4/5 Stars

Barry Sullivan has an absolute field day as a homicide cop, Lt. Collier Bonnabel, with very calculated methods of getting to the root of every crime. Whether it comes by pushing, cajoling, romancing, tricking, or flattering — he’ll do whatever is necessary. What matters to him is to keep stretching them because everyone has a breaking point. You just have to know how to work them so they slip up.

Barry Sullivan has an absolute field day as a homicide cop, Lt. Collier Bonnabel, with very calculated methods of getting to the root of every crime. Whether it comes by pushing, cajoling, romancing, tricking, or flattering — he’ll do whatever is necessary. What matters to him is to keep stretching them because everyone has a breaking point. You just have to know how to work them so they slip up.

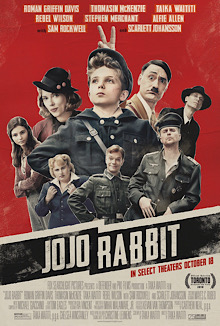

We must acknowledge the elephant, or rather, the rabbit, in the room. Grappling with the intersection of Nazis and humor has always been a loaded and controversial topic. But usually, it fosters conversation nonetheless so here’s an attempt to provide some meager context.

We must acknowledge the elephant, or rather, the rabbit, in the room. Grappling with the intersection of Nazis and humor has always been a loaded and controversial topic. But usually, it fosters conversation nonetheless so here’s an attempt to provide some meager context.

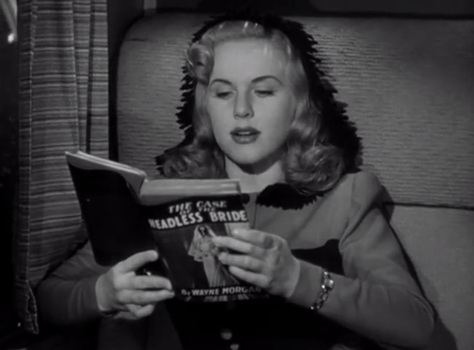

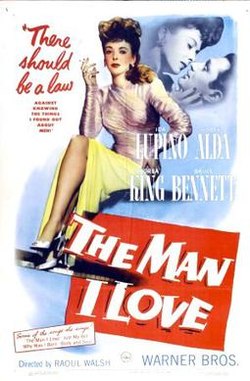

It feels like we might have the courtesy of a bit of Gershwin masquerading under the cloak of noir. We find ourselves at a hole-in-the-wall jazz joint after hours. Club 39 feels free and easy with an intimate jam sesh. Petey Brown (Ida Lupino) is having fun with a rendition of “The Man I Love.”

It feels like we might have the courtesy of a bit of Gershwin masquerading under the cloak of noir. We find ourselves at a hole-in-the-wall jazz joint after hours. Club 39 feels free and easy with an intimate jam sesh. Petey Brown (Ida Lupino) is having fun with a rendition of “The Man I Love.” Of the plethora of returning G.I. films and film noirs, this one reflects their fears most overtly and for this very reason, it might be generally the most forgotten today. That and the assembly of a lower-tier cast. Most of these names have been lost to time.

Of the plethora of returning G.I. films and film noirs, this one reflects their fears most overtly and for this very reason, it might be generally the most forgotten today. That and the assembly of a lower-tier cast. Most of these names have been lost to time.