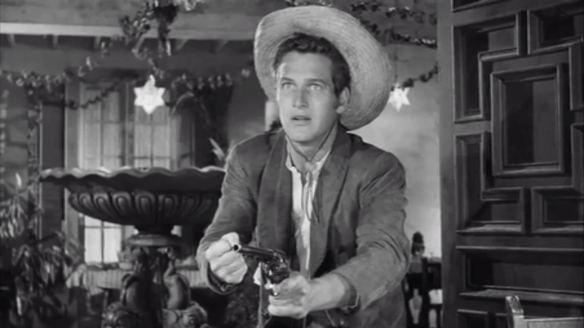

As it turns out, Paul Newman’s a real barn burner. His family name is synonymous with conflagrations and it’s a great entry point for a character, in this case, a drifter named Ben Quick who’s run out of town by the local judge.

As it turns out, Paul Newman’s a real barn burner. His family name is synonymous with conflagrations and it’s a great entry point for a character, in this case, a drifter named Ben Quick who’s run out of town by the local judge.

We never actually know if he was guilty of arson or not but we assume he must be. And so even with the audience, Quick carries that onus because the reputation seems to fit him. He’s a leering no-good, not to be trusted with money or women. It’s all speculation, mind you, though it cuts pretty close to the truth.

He receives some southern hospitality when a car screeches to a stop to pick him up. In the passenger’s seat is Eula (Lee Remick) with a coaxing sensuality accentuated by a sing-song twang that’s irresistible. More reserved is the driver, Clara (Joanne Woodward), who sees through Quick just like most people. She’s not about to be taken in by his animal magnetism.

This is just the beginning of a vast family drama and the names we have to thank are director Maritn Ritt, still trying to get his head above water after a blacklisting, and screenwriting stalwarts Irving Ravitch and Harriet Frank Jr.

Their tale was realized by weaving together three stories by William Faulkner that I have no prior knowledge of, matched with the atmospherics of a Tennessee Williams sweaty drama. In fact, it was released before a couple films that share more than superficial similarities, namely the well-remembered Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) also starring Newman, this time opposite Elizabeth Taylor and Burl Ives. Then, there was God’s Little Acre (1958) which was probably the quirkiest and most erratic of the trio starring Robert Ryan as the head of the family.

Arguably, there’s no larger-than-life figure than Orson Welles to take the part of the portly patriarch of the Varner clan, Will, a man who puts his stamp on the local town. After a stint in the hospital with ailments, he comes back in fashion, sirens howling, so everyone knows that the king has returned. First, it’s a visit to his mistress (Angela Lansbury) who’s anxious to get married so she can have more stability. His responses remain evasive.

The Louisianna heat is no fluke and Welles is perpetually perspiring. He lends an earthiness to the proceedings that undoubtedly takes some cues from Ritt. Will Varner laughs boisterously at the catcalls of young boys directed towards his daughter-in-law, just as he conspires to get his other daughter hitched up so grandchildren can start popping out. In this regard, he’s very pragmatic (if not misogynistic). He wants heirs to maintain the family name because his gutless son certainly isn’t going to be the one to do it.

While important to the stability of the picture, by all accounts, Welles was a terror to work with for everyone on set. There are multiple indications of why this might have been. It’s all too probable he felt pressured and slightly insecure with the young upstarts coming on the scene from the Actor’s Studio, including Marlon Brando and his current co-star Paul Newman. Alternatively, with Welles being the renowned directorial power that he was, there was probably some dissatisfaction on his part because he couldn’t pull all the strings and have total control like he was normally accustomed to.

However, put him together in a room with Paul Newman and you have two men in front of you as crooked as a barrel of fish hooks. Varner’s perceptive daughter puts it aptly, “One wolf recognizes another.” Soon they strike up a mutually beneficial deal throwing other people and lives around like they were pawns in a chess match to solely serve the two of them.

Varner wants a form of southern immortality. Males to bear his name and people to sing his praises and tame the land in a sprawling estate with spoils to match what he has accumulated over his lifetime. Quick, why, he just wants money and land and whatever else he can finagle out of the old man. What unites them is they’re both out for number one.

Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward go on their first cinematic date together and it’s a picnic in the park that ends prematurely. In real life, they would get married soon after principal photography wrapped and as they say, the rest was history. They stayed married for another 50 years until Newman’s passing in 2008. For a Hollywood marriage, this has to be some kind of record.

But regardless of what was going outside the frame, what is within the confines of the space is just as enchanting for the simple reason that they make some amount of palpable magic together. There’s a tension between them but then a certain attraction and pull that leads to oscillation back and forth in a continuous orbit of gravitation and then distaste.

In real life, it’s not what leads to stable romance but in film, it’s what dreams are made of because every sequence has an intangible undercurrent of spiritedness. It’s in the eyes twinkling. The unspoken words along with the spoken ones. Maybe it’s a lot of making something out of nothing but I would like to think it isn’t. They have something electric together.

Just as the film opened with fire, it’s another barn burning that ends the picture and gets the town in a tizzy. The irony is the very event that looks to be a dramatic firecracker actually reconciles a father and son. That’s the thing about The Long Hot Summer; it has the guts — some might say the gall — to end on an optimistic note without plunging into the throes of deep dark tragedy. Sometimes the 50s dramas take it too far. It’s almost as if they forget some of the greatest dramas historically were as much comedy as they were tragedy.

With so much talent, I’m inclined to like this one and since it all but led the pack coming out of the gates, it deserves some kudos. But best of all, the partnership between Martin Ritt, Ravitch, Frank, and Newman was just beginning, not to mention a marriage for the ages. It’s part of the reason why one can come away from The Long Hot Summer with a smile as wide as Will Varner’s.

3.5/5 Stars

Pleasant surprises abound in Incredibles 2. What is supremely evident is that Brad Bird still has a pulse on quality storytelling just as the overall animation is blessed by the continual technological advancements in the medium.

Pleasant surprises abound in Incredibles 2. What is supremely evident is that Brad Bird still has a pulse on quality storytelling just as the overall animation is blessed by the continual technological advancements in the medium.

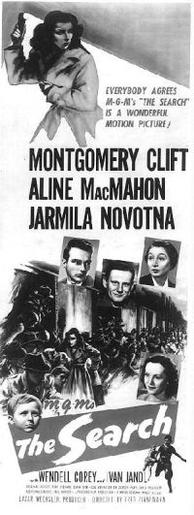

Any knowledge of director Fred Zinnemann only aids in informing The Search. Formerly living in a Jewish family in Austria, he would immigrate to the bright lights of Hollywood in the 1930s only to have both his parents killed in the Holocaust. So if you think he had no stake in this picture you would be gravely mistaken.

Any knowledge of director Fred Zinnemann only aids in informing The Search. Formerly living in a Jewish family in Austria, he would immigrate to the bright lights of Hollywood in the 1930s only to have both his parents killed in the Holocaust. So if you think he had no stake in this picture you would be gravely mistaken. Leave No Trace instantly reminded me of two distinct reference points. The first relates to a man named Richard Proenneke who lived in the Alaskan wilderness for 30 years building his own cabin and raising his own food in a life of tranquil solitude.

Leave No Trace instantly reminded me of two distinct reference points. The first relates to a man named Richard Proenneke who lived in the Alaskan wilderness for 30 years building his own cabin and raising his own food in a life of tranquil solitude.

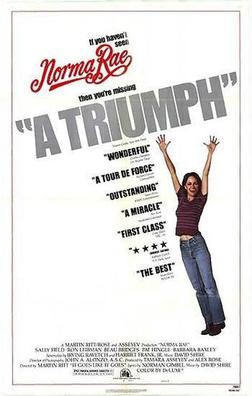

If you had any trouble possibly liking Sally Field before — consequently, one of the sweetest actresses ever to cross the screen — then there’s little gripe to be had with her any longer. Norma Rae really does feel like a gift for her. Both as a story to be a part of and a character to portray since both speak to us intuitively as an audience.

If you had any trouble possibly liking Sally Field before — consequently, one of the sweetest actresses ever to cross the screen — then there’s little gripe to be had with her any longer. Norma Rae really does feel like a gift for her. Both as a story to be a part of and a character to portray since both speak to us intuitively as an audience.