Douglas Sirk’s films are always lovely to look at, almost to the point of making you sick. The panoramas swell with color. They’re too perfect. The sets are gaudy — the cars the same — to the point of almost being unsightly in their over the top artificiality. Try to find any amount of authenticity and you will most likely fail.

The people within the frames are even more glamorous than the rooms they fill and arguably more colorful. Namely the dashing Rock Hudson, a Sirkian mainstay and then Lauren Bacall, Dorothy Malone, and Robert Stack, all Hollywood talents playing character types with names and dialogue straight out of a trashy romance novella. We wouldn’t have it any other way. It’s exquisite.

Because everything is played with the utmost of seriousness from starting credits to the closing shot and yet it just doesn’t take. Sirk seems to be working against his material and that’s where the enjoyment of this picture really lies. It makes Written on the Wind the zenith of the soap opera tradition.

Like any good melodrama, it begins with a shooting, it ends with a murder inquest and the in between is filled in with drunkenness, romantic interplay, familial strife, impotence, fist fights, childhood dynamics, and anything else you can imagine in such a sleazy affair. Still, when everything has run its course, our leading man and his leading lady are able to drive through the pearly mansion gates off on a perfect life together.

Though Rock Huson and Lauren Bacall are arguably our stars, it is their fairly typical and straightforward roles lay the groundwork for the true show put on by Malone and Stack as the Hadley siblings.

Malone sheds her librarian role in The Big Sleep (1946) for the performance of her career as the uninhibited, diabolical, sex-crazed platinum blonde. And Stack is a far cry from Elliot Ness. He lives like he’s never even heard of prohibition as he lets his characterization go completely off the rails in a fantastic manner.

Their father (Robert Keith) is one of the richest oilmen around and they’ve grown up as brats accustomed to wealth and yet their lives are an utter shambles with flings, booze, and personal demons leaving a wake of tumult that rips through the tabloids.

Mitch Wayne (Hudson) and Lucy Moore (Bacall) meet in a boardroom as nice as you please. You would guess that romance is kindling except that the impetuous Kyle (Stack) inserts himself in the situation trying to win her over with jet flights and a steady stream of charm. Somehow it works and they are wedded soon thereafter. It has all the signs of a trainwreck given Kyle’s track record but miraculously it works for a while. But he’s devastated by some news from his local doctor (Ed Platt) which drives him back into a constant stupor and drunken tirades.

Meanwhile, his sister relishes watching him falter because they’ve never seen eye-to-eye on anything. Her main focus is seducing Mitch their lifelong friend who has never allowed himself to fall prey to her wiles. In retaliation, she looks to search out any man who can show her a decent time. She doesn’t much care who it is. But Mitch is hardly jealous for her, only protective, and his eyes are set on Lucy nee Moore anyways. If the entanglements aren’t clear already they present themselves obviously enough. It’s gloriously sensationalized nonsense.

Still, so many others owe an undying debt to this film and those like it. Fassbinder came from here as did Todd Haynes. Dallas, Dynasty, or any other 80s soaps found their roots right here too. After all, this is the original version of “Who Shot J.R.” Thus, the debt must be paid to Sirk’s films and people have.

Because his style is very easy to admire. Contemporary audiences undoubtedly ate it up and we do now years later. The artificial interiors and the airbrushed Technicolor palette helps define what many people deem to be 1950s Hollywood. It’s luscious, easy on the eyes, decadent, all those apt superlatives. But if that was all that he had to offer, Sirk wouldn’t be as interesting to a great many people now.

It’s the very fact that he seems highly self-aware and he’s so wonderful at staging and creating this environment, beautifully photographed by his longtime collaborator Russell Metty, that the whole composition tells us something more. It’s rear projections and painted backdrops. Sets and stages that accentuate this piece of drama. It’s all sending us a collective wink to see if we get the joke. Those who do will be greatly rewarded.

4.5/5 Stars

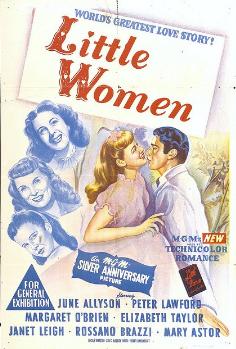

In the recent days, I gained a new appreciation of June Allyson as a screen talent and in her own way she pulls off Jo March quite well though it’s needlessly difficult to begin comparing her with Katharine Hepburn or Winona Ryder.

In the recent days, I gained a new appreciation of June Allyson as a screen talent and in her own way she pulls off Jo March quite well though it’s needlessly difficult to begin comparing her with Katharine Hepburn or Winona Ryder.

“The more you know about women the less you know about women.” It’s the story of my life and also a marvelous entry point for this film because it really is a throwaway line. It’s referred to several times thenceforward but really means nothing more. Anyways, if we came to this film simply for the plot it would have been buried under heaps of other more elegant or frenetic comedies over the years. But the reason to revisit this one for all those eager thespians out there is solely for the dancing and what dancing it is.

“The more you know about women the less you know about women.” It’s the story of my life and also a marvelous entry point for this film because it really is a throwaway line. It’s referred to several times thenceforward but really means nothing more. Anyways, if we came to this film simply for the plot it would have been buried under heaps of other more elegant or frenetic comedies over the years. But the reason to revisit this one for all those eager thespians out there is solely for the dancing and what dancing it is.