“This man bears a cross called cancer. He’s Christ.”

Ikiru is instantly a tale of dramatic irony as we see x-ray footage and an omniscient narrator tells us matter-of-factly the signs of cancer are already obvious. Our protagonist’s work life hits hard as he’s a public affairs section chief — dangerously close to my own title — thoroughly buried in the bureaucracy of Japan.

The great tragedy is how he’s never actually lived. He’s killing time, stamping documents with his inkan (official seal). I know it well because I sat at a desk in Japan watching others doing much the same. There were fewer teetering paper mountaintops around me, but the sentiment holds true. All his will and passion evaporated over the past 20 years. How this happened is made quite clear. We are once again privy to the dizzying circular bureaucracy that I’ve been subjected to in my own lifetime, from college campuses and also living abroad in Japan.

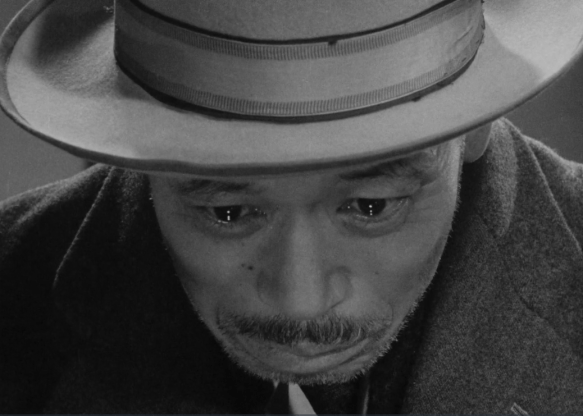

Even as he portrays a man of such a sorry constitution, there’s something instantly endearing about Takashi Shimura. In fact, he has been a friend of mine for quite some time. Aside from Toshiro Mifune and Setsuko Hara, he might be one of Japanese cinema’s most instantly recognizable icons. There’s a glint in his eyes of warmth that so quickly can turn to melancholy. It serves him well in Ikiru as do his distinguished features and graying hair. The dejectedness up his posture, the glumness in his being, verges on camp but it never loses its purpose.

The greatest revelation is the composition of the film itself in the hands of Akira Kurosawa and his editor Koichi Iwashita. I never recalled the editing of the picture, cutting and shifting between time periods. The delight in his son Mitsuo’s athletic prowess only for it to be crushed seconds later on the basepaths. Then, there was the boy’s appendix operation, an event he was not able to stay around for. It paints the relationship with his son, drifting through time, as the world spins around him, and Kurosawa follows the motion to find the heart of his picture.

As Watanabe sinks lower, taking an unprecedented leave from work, leaving all the underlings to surmise the reason, he meets a lowly fiction writer in a bar. The man’s occupation gives him a bit of license to wax philosophical, and he’s more forthcoming, more whimsical than we’re accustomed to coming across, especially in Japanese culture. He tries to empower the dying man to live it up.

After all, greed is a virtue, especially greed in enjoying life, and so they take to the night scene with reckless abandon blowing Watanabe’s savings in the process. For a night he tries on the life of a profligate and a drunkard with middling results. There are light-up pinball machines, rowdy smoke-filled beer halls, and lively streets overrun by women of the night. They proceed to make their way to every conceivable bar imaginable. As the montage and music roll on and on, I couldn’t help but recall The Best Years of our Lives.

It was a celebration under very different circumstances. A soldier comes back from V-J Day ready to live it up. But much like Watanabe-san, Al (Fredric March) is looking to put off the inevitable for a bit longer. It’s a lot easier to face this heightened reality than the morning after. It’s a diversion tactic.

In one space the two merrymakers totter up the stairs as couples dance cheek to cheek. Their destination seems to be the lively piano bar jumping with tons of western-infused honky-tonk rhythm and blues. But Watanabe-san subsequently brings the mood to a standstill as the house stops to watch him sing a melody born out of the melancholy of the past — reminding us life is brief.

To this point, he feels pitiful almost laughable, laid prostrate by his very drunkenness, and gallivanting around the streets to the sidewalk symphony of honking taxi cabs and the distinct notes of “Bibbity Bobbity Boo.”

The morning after is what we expect. Not only a hangover but real-life sets in and the baggage that comes with it. He realizes his son and daughter-in-law are completely absent. Not only absent; they are indignant about his behavior. Because of course, they don’t understand. He hasn’t told them anything.

Instead, he gravitates toward the youth of his garrulous young colleague (Miki Odagiri) bursting with untapped spunkiness. The key is how she makes up for his lack of both humor and energy. She somehow uplifts him with her very spirit — teaches him what it means to really live — what it is to have giggle fits. From the outside looking in, without his context, it looks like a sordid romance or some odd preoccupation. It’s more innocent than that.

He recounts how when he was a little kid, he was drowning in a pond; everything was going black as he writhed and thrashed around in the deep void around him. He felt the very same sensation when he found out about his illness — all alone in the world — his son as distant as his mother and father were when he was in the water. Full stop.

Ikiru and the act of living life are split into two distinct segments. Much of it is expounded upon after the inevitable happens and Watanabe-san has passed away. It’s one of the most abrupt deaths in film history. But that was never the point. Death was inevitable. What mattered is how he used the time before. How he lived it out. This tangles with the existential questions of life itself with all its subjectivities.

It sounds callous to say Kurosawa uses the motif, but what unfolds, in narrative terms, is like Rashomon meeting an abridged Citizen Kane. It’s artful and extraordinary taking the recollections of all the observers in his life to try and make sense of this man’s final hours.

The extended scene that follows almost plays out like a parable for me; it makes the dichotomy so apparent even as it expresses so much about these human beings. His fellow bureaucrats shed no tears at his wake. They have no gifts or kind words for him. And yet a host of working-class women, women who only knew him for a very few hours, anoint his burial with tears and burn incense for him.

The rich and well-to-do have no humility, no need, no appreciation because they’ve allowed themselves to be insulated — they believe they’ve brought every good thing on themselves. Revelation falls to those who are less fortunate, who have spent their whole lives impoverished and low. They can appreciate how a simple action by a simple man can be ripe with the kind of profound meaning these men sitting around idly by will never comprehend (much less believe).

It’s admittedly out of left field, but one of the songs I was taken with last year was COIN’s infectious pop record “Cemetery.” Its most gutting line goes, ” Never made time for the family but he is the richest man in the cemetery.” The words terrify me to death, and they inform how I think about Ikiru — its purpose — the meaning of Mr. Watanabe-san’s final act of unswerving resolve.

It’s a warning and a cry, a pronunciation and a prayer for all those who are willing to pay it heed. What is life but to be lived out? There are only a finite amount of hours and days between “In the beginning” and “The end.” There’s no hitch on a hearse. All we can take away from this life is that which is given away. Ikiru must only be understood out of this profound paradox.

Because these men — these acquaintances sit on their duffs partaking of his family’s hospitality — trying as they might, to make sense of the mystery of his transformation. How could this be? What would cause a man to be so radically different even cavalier with both his time and his resources? They quibble about it incessantly as Watanabe-san’s actions make fools of the wise.

It’s really very simple. He says it himself even as he’s half doubled-over with pain, his voice on its last rasping legs, constantly being humiliated. “I can’t afford to hate people. I haven’t got that kind of time.” What if that was our mentality? When I look around me, who is my neighbor? It is anyone and everyone. Not just my friends but the ones who ridicule me — the ones who are hard to live with. What if spent less of my time criticizing and hating and more time loving and living. After all, aren’t they one and the same?

5/5 Stars

High and Low (or Heaven and Hell in the original Japanese) is a yin and yang film about the polarity of man in many ways. Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) is an affluent executive in the National Shoe Company. He worked his way up the corporate ladder from the age 16, because of his determination and commitment to a quality product. Now his colleagues want his help in forcing the company’s czar out. They come to his modernistic hilltop abode to get his support. Instead, they receive his ire, splitting in a huff. What follows is a risky plan of action from Gondo that is both fearless and shrewd. He takes all his capital to buy stock in the company so he can take over, but his whole financial stability hangs in the balance. He knows exactly what it means, but he wasn’t suspecting certain unforeseen developments.

High and Low (or Heaven and Hell in the original Japanese) is a yin and yang film about the polarity of man in many ways. Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) is an affluent executive in the National Shoe Company. He worked his way up the corporate ladder from the age 16, because of his determination and commitment to a quality product. Now his colleagues want his help in forcing the company’s czar out. They come to his modernistic hilltop abode to get his support. Instead, they receive his ire, splitting in a huff. What follows is a risky plan of action from Gondo that is both fearless and shrewd. He takes all his capital to buy stock in the company so he can take over, but his whole financial stability hangs in the balance. He knows exactly what it means, but he wasn’t suspecting certain unforeseen developments. At this point, the police are called and they arrive incognito, ready to stake out the joint and do the best they can to get the boy back safe and sound. This section of the film almost in its entirety takes place within the confines of Gondo’s house and namely the front room overlooking the city. It’s the perfect set up for Akira Kurosawa to situate his actors. He uses full use of the widescreen and his fluid camera movements keep them perfectly arranged within the frame.

At this point, the police are called and they arrive incognito, ready to stake out the joint and do the best they can to get the boy back safe and sound. This section of the film almost in its entirety takes place within the confines of Gondo’s house and namely the front room overlooking the city. It’s the perfect set up for Akira Kurosawa to situate his actors. He uses full use of the widescreen and his fluid camera movements keep them perfectly arranged within the frame. Finally, with the help of Shinichi, they make a startling discovery that ties back to the kidnapper. And the boy’s drawings along with a colorful stream of smoke help them move in ever closer. What follows is an elaborate web of trails through the streets as they work to catch the culprit in his crime, to put him away for good. And it works.

Finally, with the help of Shinichi, they make a startling discovery that ties back to the kidnapper. And the boy’s drawings along with a colorful stream of smoke help them move in ever closer. What follows is an elaborate web of trails through the streets as they work to catch the culprit in his crime, to put him away for good. And it works. But High and Low cannot end there without a consideration of the consequences. Gondo has been brought low. He’s losing his mansion and must start a new job on the bottom of the food chain once more. His enemy requests a final meeting as he prepares for his imminent fate, and this is perhaps the most grippingly painful scene. Gondo’s face-to-face with the man who made him suffer so much. Toshiro Mifune’s violent acting style serves him well as he wrestles so intensely with his own conscience. And yet at this junction, he is past that. What is he to do but listen? In this way, it’s difficult to know who to feel sorrier for — the man who is resigned to a certain fate passively or the one who goes out proud and arrogantly against death. Both have entered some dark territory and it’s no longer about high or low or even heaven and hell. They’re stuck in some middle ground. An equally frightening purgatory.

But High and Low cannot end there without a consideration of the consequences. Gondo has been brought low. He’s losing his mansion and must start a new job on the bottom of the food chain once more. His enemy requests a final meeting as he prepares for his imminent fate, and this is perhaps the most grippingly painful scene. Gondo’s face-to-face with the man who made him suffer so much. Toshiro Mifune’s violent acting style serves him well as he wrestles so intensely with his own conscience. And yet at this junction, he is past that. What is he to do but listen? In this way, it’s difficult to know who to feel sorrier for — the man who is resigned to a certain fate passively or the one who goes out proud and arrogantly against death. Both have entered some dark territory and it’s no longer about high or low or even heaven and hell. They’re stuck in some middle ground. An equally frightening purgatory.