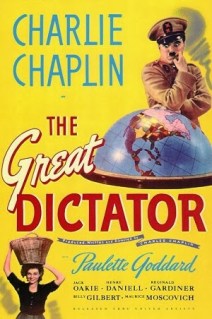

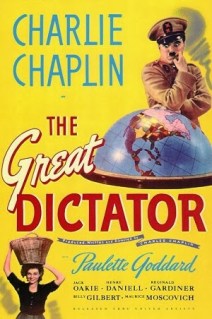

Charlie Chaplin was not just a movie star, he was an American icon and his fame did not simply end in the States but reached all over the globe. Furthermore, his name is synonymous with the Little Tramp who is still widely known to this day. True, Chaplin had rough patches, through numerous marriages and some unpopularity later in life, but in the early half of the 20th century, he was king. The Great Dictator not only showcased his artistry but also lambasted Hitler’s Nazi regime through the usage of outrageous humor. He used his adept skill at balancing comedy and pathos to win critical acclaim, but it also generated some controversy. Moreover, The Great Dictator is an important cultural artifact that is a reminder of a tense moment in world history.

Charlie Chaplin was not just a movie star, he was an American icon and his fame did not simply end in the States but reached all over the globe. Furthermore, his name is synonymous with the Little Tramp who is still widely known to this day. True, Chaplin had rough patches, through numerous marriages and some unpopularity later in life, but in the early half of the 20th century, he was king. The Great Dictator not only showcased his artistry but also lambasted Hitler’s Nazi regime through the usage of outrageous humor. He used his adept skill at balancing comedy and pathos to win critical acclaim, but it also generated some controversy. Moreover, The Great Dictator is an important cultural artifact that is a reminder of a tense moment in world history.

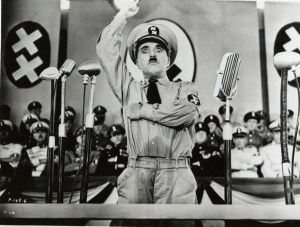

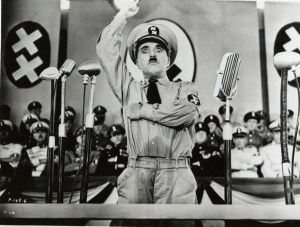

Charlie Chaplin was a perfectionist in all areas of his films and he was not any different when it came to The Great Dictator. He produced, directed, and of course, acted in the film. He played the sympathetic figure of the Jewish barber and then he delivered a grossly different performance as Adenoid Hynkel, an obvious caricature of Adolf Hitler. In fact, the first scene with Hynkel is utterly fascinating because it is so very different than anything Chaplin ever attempted before. It is a far fling from his archetypal everyman, and yet he proves his brilliant acting ability. In this introductory sequence, the Phooey is about to give a speech to his many supporters. As far as staging and cinematography go the scene is quite minimalistic. Some high-level officials sit behind their leader with a few microphones in the foreground. Cuts go almost unnoticed, the position of each shot barely changes, and the camera hardly strays from the face of the Great Dictator. The obvious focus of it all is meant to be Chaplin’s mustached masquerade. His goal is to closely emulate Hitler but then exaggerate and ridicule the Nazi leader in the same instance. During the entire sequence, the Dictator violently gesticulates and orates while an understated translator deciphers the Germanic sounding gibberish. One moment Hynkel will be thrusting his fist up in the air in a triumph of the Tomanian will. The next he condemns democracy, liberty, and freedom of speech before spouting off more propaganda about Tomania’s formidable military. His mood swings are intense and he has sudden emotional lapses especially when he recalls his former struggles with his comrades Herring and Garbage (parodies of Herman Goring and Joseph Goebbels). All the while Chaplin mixes familiar words such as Wiener schnitzel, sauerkraut, Bismarck, and blitzkrieg with, coughs, sputters, and grunts to create a sort of “Gibberman.” That along with the gestures, body language, and mustache creates an extraordinary caricature of Hitler. Chaplin is so adept when it comes to minutiae like bouncing up and down on his feet, crossing his arms, or even wiping his tears on his tie. At times these movements can easily be overlooked because they appear so natural and these small details can get overshadowed by the outrageous dialogue and gestures. Chaplin’s film ultimately succeeds thanks to the laurels of his acting ability which allows him to so aptly impersonate Hitler in an irreverent way.

On the surface The Great Dictator certainly is a comedy, however, perhaps even more so, it is an indictment and mockery of the corrupt tyrant who was Adolf Hitler. As is the hope with all satire, Chaplin undoubtedly wanted the American public and the whole world to know how absurd and dangerous this man was. Possibly the most alarming moment in the opening speech follows the patriotic description of the Aryan which is then harshly juxtaposed with the Jews. The Aryan was the Tomanian (or German) ideal of strong men, blonde-haired, blue-eyed women, and youth who would ultimately be “soldiers for Hynkel.” However, with the mention of Jews, Hynkel positively grinds his teeth at the word. Up to this point, Chaplin’s performance is utterly farcical, but in this one instant he makes us shiver. It is important to note that this is one of the only times the camera comes in for a close-up. Since this hardly ever happens in the sequence it is surprisingly uncomfortable. Despite, the fact that the translator matter-of-factly comments that Hynkel “Just referred to the Jewish people,” Chaplin’s actions as Hynkel say otherwise. He did not just refer to them; he positively strangles them with his diction and bends them to his will, much like the nearby microphones. Thus, when Hynkel goes on another tirade and the translator says that “for the rest of the world he has nothing but peace in his heart,” you completely distrust him and Chaplin uses these discrepancies for comic effect. However, they also act as a commentary on the persona of Hitler and these inconsistencies ultimately suggest that, he too, is not to be trusted. With his directing and acting, Chaplin implies numerous other things of Hitler as well. Hynkel is power hungry, unstable, tyrannical, and dangerous to the rest of the world. The same could be said of Hitler. However, despite his oddities, Hynkel is a commanding orator who knows how to win the people over in order to control their ideology. Yet again, the same applies to Hitler. As a staunch American and believer of democracy, Chaplin attempts to bring attention to these dangers and he only hopes his audience will be attentive. His purpose was not just to make a critically acclaimed piece of art. Behind Chaplin’s art, there was an earnest purpose that transcends simple comedy.

On the surface The Great Dictator certainly is a comedy, however, perhaps even more so, it is an indictment and mockery of the corrupt tyrant who was Adolf Hitler. As is the hope with all satire, Chaplin undoubtedly wanted the American public and the whole world to know how absurd and dangerous this man was. Possibly the most alarming moment in the opening speech follows the patriotic description of the Aryan which is then harshly juxtaposed with the Jews. The Aryan was the Tomanian (or German) ideal of strong men, blonde-haired, blue-eyed women, and youth who would ultimately be “soldiers for Hynkel.” However, with the mention of Jews, Hynkel positively grinds his teeth at the word. Up to this point, Chaplin’s performance is utterly farcical, but in this one instant he makes us shiver. It is important to note that this is one of the only times the camera comes in for a close-up. Since this hardly ever happens in the sequence it is surprisingly uncomfortable. Despite, the fact that the translator matter-of-factly comments that Hynkel “Just referred to the Jewish people,” Chaplin’s actions as Hynkel say otherwise. He did not just refer to them; he positively strangles them with his diction and bends them to his will, much like the nearby microphones. Thus, when Hynkel goes on another tirade and the translator says that “for the rest of the world he has nothing but peace in his heart,” you completely distrust him and Chaplin uses these discrepancies for comic effect. However, they also act as a commentary on the persona of Hitler and these inconsistencies ultimately suggest that, he too, is not to be trusted. With his directing and acting, Chaplin implies numerous other things of Hitler as well. Hynkel is power hungry, unstable, tyrannical, and dangerous to the rest of the world. The same could be said of Hitler. However, despite his oddities, Hynkel is a commanding orator who knows how to win the people over in order to control their ideology. Yet again, the same applies to Hitler. As a staunch American and believer of democracy, Chaplin attempts to bring attention to these dangers and he only hopes his audience will be attentive. His purpose was not just to make a critically acclaimed piece of art. Behind Chaplin’s art, there was an earnest purpose that transcends simple comedy.

In essence, Chaplin told two stories with The Great Dictator and this allowed his film to have a greater impact. The scene I scrutinized put a great deal of emphasis on the title character, Adenoid Hynkel. Chaplin could have simply told the satirical story of Hynkel in a way that derided such works as Mein Kampf or The Triumph of the Will. I think he did this well, but it is important to realize he did not stop there with his critique. He also represented the plight of the Jewish barber who signified not only the struggles of the Jews but of many people during the Nazi terror. Chaplin develops a great deal of sympathy for this innocent barber, and it causes the audience to be moved. As a result, there is a desire for him to succeed and though there are times when we might laugh, it is almost always with him and not at him. In one last emotional set piece Chaplin has the masquerading barber speak in the place of the dictator. He pleads with humanity to fight for peace, as ardently as Adenoid Hynkel had condemned the Jews and lauded his own army earlier. Like Chaplin and Hitler, these two cinematic figures share a few similarities, and Chaplin utilizes these features to great effect. Because Hynkel is so outrageously crazy, it amplifies the degree in which we empathize with the barber and he strikes us as all the more guiltless, while the dictator grows even more vindictive in comparison.

Chaplin began his production of The Great Dictator in a tense moment in history and his film is important when we consider that era. After 1933, Hitler was on the rise and the threat of the Nazis was becoming increasingly imminent. But in Europe, and even more so in the United States, people did not realize just how dangerous he was. Chaplin was an artistically gifted man, but also a political man who was aghast at Hitler. He knew the idealized leader portrayed in Triumph of the Will could be used as deadly propaganda to influence the masses. Furthermore, he must have also known that he had often been labeled as a Jew himself because he portrayed characters contrary to the Aryan ideal. Unlike other members of Hollywood, Chaplin did not shrink back because he was afraid of the repercussions in Germany. In fact, during this early war period, he created one of only a few films which actually tackled the issue of Hitler and the Nazis. A couple other titles would be Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939) by Warner Bros. and then To Be or Not to Be (1942) by Ernst Lubitsch. The Great Dictator was not the first of these films to be released. However, out of these titles, The Great Dictator was probably the most celebrated and perhaps the most blatantly anti-Hitler. The American public loved the film for its comedy, which was in line with many of Chaplin’s former classics. However, Chaplin did not try and hide anything behind the film. This is not a veiled parody of Hitler; it is extremely obvious. Looking at the political climate in which he was making this movie, it is an amazing piece of cinema. In some respects it is surprising it was so well received and yet I suppose it is a testament to Chaplin and the clout that he still carried up to this point in time. You could say that Charlie Chaplin willfully took on Adolf Hitler with the film, and in many ways, Chaplin was the victor. That is quite an extraordinary achievement. Of course, with all the prestige that goes with this film, there will always be controversy. The fact is, it covers a very sensitive topic, and the use of humor can often be frowned upon as insensitive in such circumstances. Chaplin said himself that if he had “known about the actual horrors of the German concentration camps, [he] could not have made The Great Dictator.” However, it is fair to say he did not know and also this film is certainly not making light of the plight of the Jews. On the contrary, it empathizes with them so that audiences will be on their side. Thus, this film seems to be made of more good than bad and I think it is safe to say that Chaplin can be commended for the work he did.

Charlie Chaplin began humbly, then started a career in the infant film industry, and never looked back. As iconic as Charlie Chaplin is, it is difficult to refute the fact that he was a tremendously skilled performer and filmmaker who knew his craft well. The Great Dictator worked so wonderfully on multiple levels as a comedic flick and a biting satire of one of the world’s most notorious villains. Specifically, in the opening scene with Adenoid Hynkel, Chaplin creates an uproarious caricature of Hitler that is realistic enough and yet so scatterbrained to work within the context of the film. Then, Hynkel is effectively juxtaposed with the little Jewish barber who radiates naiveté. Chaplin was bold to say the least. He retired his most famous character, he made his first sound film, he played two roles, and of course, he made fun of Hitler. I suppose we would expect nothing less from one of the greatest film stars of all time. However, Charlie Chaplin not only gave us a comedic assault on Hitler, it was an indictment of anti-Semitism, a rallying call for democracy, and an urgent and universal plea for action.

Fritz Lang’s archetypal sci-fi epic is steeped in politics, religion, and humanity, but above all, it is a true cinematic experience. It is visually arresting, and it still causes us to marvel with set-pieces that remain extraordinary. How did Fritz Lang piece together such a gargantuan accomplishment? Maybe even equally extraordinary, how was I able to see almost a complete cut of this film, which was at different times thought to be lost, incomplete, and ruined?

Fritz Lang’s archetypal sci-fi epic is steeped in politics, religion, and humanity, but above all, it is a true cinematic experience. It is visually arresting, and it still causes us to marvel with set-pieces that remain extraordinary. How did Fritz Lang piece together such a gargantuan accomplishment? Maybe even equally extraordinary, how was I able to see almost a complete cut of this film, which was at different times thought to be lost, incomplete, and ruined? In a sense, with Metropolis, we can easily see a precursor to Chaplin’s Modern Times a decade later. There is a general apprehension of the machine and the impact of a true industrial revolution. There is a fear that there are more positives than negatives. That machines will take over and man will become outdated. Perhaps someday our creation will destroy us. By today’s standards, such notions seem archaic, but are they? We still live in a society ever more obsessed with advancement, technology, and all the things that come with that. However outdated some of Metropolis might feel, and there are numerous such moments, at its core is the final resolution that between the body and the mind there must be a heart to regulate. We are not simply animals with bodies or rational machines with minds, but the beauty of humanity is that we have a heart, pulsing with life and vitality. That is something to be grateful for and never lose sight of.

In a sense, with Metropolis, we can easily see a precursor to Chaplin’s Modern Times a decade later. There is a general apprehension of the machine and the impact of a true industrial revolution. There is a fear that there are more positives than negatives. That machines will take over and man will become outdated. Perhaps someday our creation will destroy us. By today’s standards, such notions seem archaic, but are they? We still live in a society ever more obsessed with advancement, technology, and all the things that come with that. However outdated some of Metropolis might feel, and there are numerous such moments, at its core is the final resolution that between the body and the mind there must be a heart to regulate. We are not simply animals with bodies or rational machines with minds, but the beauty of humanity is that we have a heart, pulsing with life and vitality. That is something to be grateful for and never lose sight of.