“You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette

“You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette

The prospect of watching Love on the Run saddened me and not for the reasons you might expect. Not because it’s noted as the weakest film in Truffaut’s famed Antoine Doinel series, although that it is. Not because it utilizes a clip show rather like a lazy sitcom as some will undoubtedly note (although this does actually give way to some rather entertaining reminisces as Antoine crosses paths with two old acquaintances). And it’s not even because this is the last film in the series and Truffaut never got around to any more installments before his death in 1983. Though that is sad.

The truly heartbreaking thing about this film is not even the fact that Antoine and Christine (Claude Jade) are getting a divorce although that is at the core of it. It’s that Antoine, who has long been the focal point of these films with his certain brand of charming charisma, really has not changed a great deal.

Time and time again, his superficial relationships with women are explored and time and time again his self-destructive habits hardly seem playfully entertaining but if you want the most honest answer, it’s all rather disheartening.

He has a new girl who we meet in the opening credits. Her name is Sabine. She’s young, radiant, very pretty and works in the local record shop. If we didn’t know any better we could easily make comparisons between her and Christine.

We see that little boy from 400 Blows and even that same young man looking to win the affection of a cute brunette named Collete. However, now a few years down the road, none of that panned out. He’s terribly selfish, undeniably a cad and always trying to say he’s sorry to save face. Sabine says it well when she calls him a pickup artist (You sure have a strange idea about relationships. You seem to only care about the first encounter. Once they’re together it’s all downhill).

However, if we look again we remember that Doinel’s home life was hardly a prize, schoolmasters were unfeeling and his mother passed away — the only real family he had in the world.

Maybe,  Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively.

Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively.

Like all the women who he tiptoed around with, as an audience, we have liked him but never truly loved him — an important distinction to make. And coincidentally, we also see right through him. Perhaps because he’s often too much like us or other times not enough like us. It’s hard to put a finger on which one it is exactly.

We leave the film essentially where it began. Antoine has once more been scolded by his girl and made up. It’s difficult to know quite precisely how to feel about that. Love on the Run is worth its nostalgia, woven in between the most recent moments of Doinel’s life. While his character is trying, he is still strangely compelling. But at this point, it’s hard to know what to do with him. Nevertheless, Francois Truffaut was unparalleled in the continuous narrative he was able to craft — flawed, personal and most certainly memorable.

3.5/5 Stars

Arguably the greatest French comic was Jacques Tati and like Chaplin or Keaton he seemed to have an impeccable handle on physical comedy, combining the human body with the visual landscape to develop truly wonderful bits of humor. Bed and Board is a hardly a comparable film, but it pays some homage to the likes of Mon Oncle and Playtime. There’s a Hulot doppelganger at the train station, while Antoine also ends up getting hired by an American Hydraulics company led by a loud-mouthed American (Billy Kearns) who closely resembles one of Hulot’s pals from Playtime. Furthermore, there are supporting cast members with a plethora of comic quirks. The man who won’t leave his second story apartment until Petain is dead and buried at Verdun. No one seems to have told him that the old warhorse has been dead nearly 20 years. The couple next door that is constantly running late, the husband pacing in the hallway as his wife rushes to make it to his opera in time. There’s the local strangler who is kept at arm’s length until the locals learn something about him. The rest is a smattering of characters who pop up here and there at no particular moment. Their purpose is anyone’s guess, and yet they certainly do entertain.

Arguably the greatest French comic was Jacques Tati and like Chaplin or Keaton he seemed to have an impeccable handle on physical comedy, combining the human body with the visual landscape to develop truly wonderful bits of humor. Bed and Board is a hardly a comparable film, but it pays some homage to the likes of Mon Oncle and Playtime. There’s a Hulot doppelganger at the train station, while Antoine also ends up getting hired by an American Hydraulics company led by a loud-mouthed American (Billy Kearns) who closely resembles one of Hulot’s pals from Playtime. Furthermore, there are supporting cast members with a plethora of comic quirks. The man who won’t leave his second story apartment until Petain is dead and buried at Verdun. No one seems to have told him that the old warhorse has been dead nearly 20 years. The couple next door that is constantly running late, the husband pacing in the hallway as his wife rushes to make it to his opera in time. There’s the local strangler who is kept at arm’s length until the locals learn something about him. The rest is a smattering of characters who pop up here and there at no particular moment. Their purpose is anyone’s guess, and yet they certainly do entertain. But as Truffaut usually does, he digs into his character’s flaws that suspiciously look like they might be his own. Antoine easily gets swayed by the demure attractiveness of a Japanese beauty (Hiroko Berghauer), and he begins spending more time with her. Thus the marital turbulence sets in thanks in part to Antoine’s needless infidelity –revealed to Christine through a troubling bouquet of flowers. It’s hard to keep up pretenses when the parent’s come over again and Doinel even ends up calling on a prostitute one more. It’s as if he always reverts back to the same self-destructive habits. He never quite learns.

But as Truffaut usually does, he digs into his character’s flaws that suspiciously look like they might be his own. Antoine easily gets swayed by the demure attractiveness of a Japanese beauty (Hiroko Berghauer), and he begins spending more time with her. Thus the marital turbulence sets in thanks in part to Antoine’s needless infidelity –revealed to Christine through a troubling bouquet of flowers. It’s hard to keep up pretenses when the parent’s come over again and Doinel even ends up calling on a prostitute one more. It’s as if he always reverts back to the same self-destructive habits. He never quite learns. Charles Trenet’s airy melody “I Wish You Love” is our romantic introduction into this comedy-drama. However, amid the constant humorous touches of Truffaut’s film, he makes light of youthful visions of romance, while simultaneously reveling in them. Because there is something about being young that is truly extraordinary. The continued saga of Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel is a perfect place to examine this beautiful conundrum.

Charles Trenet’s airy melody “I Wish You Love” is our romantic introduction into this comedy-drama. However, amid the constant humorous touches of Truffaut’s film, he makes light of youthful visions of romance, while simultaneously reveling in them. Because there is something about being young that is truly extraordinary. The continued saga of Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel is a perfect place to examine this beautiful conundrum. In fact, all in all, if we look at Doinel he doesn’t seem like much. He’s out of the army, obsessed with sex, can’t do anything, and really is a jerk sometimes. Still, he manages to maintain an amicable relationship with the parents of the innocent, wide-eyed beauty Christine (Claude Jade in her spectacular debut). Theirs is an interesting relationship full of turbulence. We don’t know the whole story, but they’ve had a past, and it’s ambiguous whether or not they really are a couple. They’re in the “friend zone” most of the film and really never spend any significant scenes together. Doinel is either busy tailing some arbitrary individual or fleeing pell-mell from the bosses wife who he has a crush on.

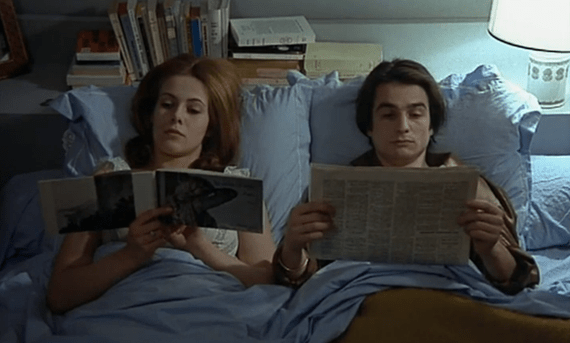

In fact, all in all, if we look at Doinel he doesn’t seem like much. He’s out of the army, obsessed with sex, can’t do anything, and really is a jerk sometimes. Still, he manages to maintain an amicable relationship with the parents of the innocent, wide-eyed beauty Christine (Claude Jade in her spectacular debut). Theirs is an interesting relationship full of turbulence. We don’t know the whole story, but they’ve had a past, and it’s ambiguous whether or not they really are a couple. They’re in the “friend zone” most of the film and really never spend any significant scenes together. Doinel is either busy tailing some arbitrary individual or fleeing pell-mell from the bosses wife who he has a crush on. By the time he’s given up the shoe trade and taken up tv repair he’s already visited another hooker, but Christine isn’t done with him yet. She sets up the perfect meet-cute and the two young lovers finally have the type of connection that we have been expecting. When we look at them in this light, sitting at breakfast, or on a bench, or walking in the park they really do seem made for each other. Their height perfectly suited. Her face glowing with joy, his innately serious. Their steps in pleasant cadence with each other. The hesitant gazes of puppy love.

By the time he’s given up the shoe trade and taken up tv repair he’s already visited another hooker, but Christine isn’t done with him yet. She sets up the perfect meet-cute and the two young lovers finally have the type of connection that we have been expecting. When we look at them in this light, sitting at breakfast, or on a bench, or walking in the park they really do seem made for each other. Their height perfectly suited. Her face glowing with joy, his innately serious. Their steps in pleasant cadence with each other. The hesitant gazes of puppy love.